3 Apr 2017

Chris Morris and Tudor Lloyd describe the case of a tissue expansion technique performed on a 10-year-old dog presenting with a cutaneous mass overlying its left lateral nasal bone.

Figure 5. Lateral view post-implantation. The expanders are visible under the skin dorsally and laterally. The arrowhead denotes the position of the "quilting suture" holding the dorsal expander in place.

Tissue expansion is becoming increasingly popular in veterinary medicine in the reconstruction of soft tissue defects through use of controlled mechanical stretch over a period of weeks to create extra skin.

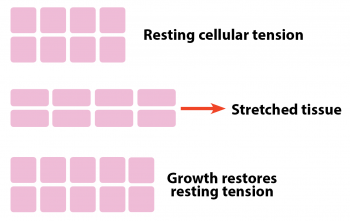

Expansion stress on dermal cells leads to an increased mitotic rate and, ultimately, the creation of new dermal cells (Figure 1). The increased skin availability means defects can be closed with less tension and a better cosmetic result than might otherwise have been achieved.

Tissue expansion is commonly used in human reconstructive surgery (Swan, 2007) and was first described in the 1950s (Neumann, 1957), but it wasn’t until 20 years later, when work was presented on post-mastectomy breast reconstruction (Bennett and Hirt, 1993; Radovan, 1982) that the concept took off.

This technique in veterinary medicine facilitates the excision of masses in locations that might otherwise have led to costly secondary wound management and repeated visits to the surgery.

One such case was that of Tiger – a 10-year-old male, neutered greyhound that presented with a cutaneous mass overlying his left lateral nasal bone at the mucocutaneous junction with his nasal planum.

The mass had been present for several years following unsuccessful removal of a cutaneous mast cell tumour (MCT) at a previous veterinary surgery. However, over several weeks, it had started to grow and his owners were becoming increasingly concerned. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable, save the 3cm SC mass extending across the dorsal and left lateral muzzle (Figure 2).

A fine needle aspirate of the mass confirmed the presence of an MCT, but, as cytology is unable to grade this malignancy, the prognosis could not be assessed. Incisional surgical biopsy was discussed with his owners, but, at their request, excisional biopsy was performed.

However, due to the location of the mass and the need for, at minimum, 20mm margin where possible, primary closure would not have been feasible. Potential existed to close the surgical wound with an axial pattern graft based on three arteries (the superior and inferior labial arteries, together with the angularis oris artery; Yates et al, 2007), but, if the flap failed, it would have had catastrophic consequences.

One further option was discussed with Tiger’s owners and that was the potential of using tissue expanders to create extra skin, reduce wound tension and thus allow primary closure without the need for an axial pattern flap.

Both of these closure techniques were offered in combination with adjunctive chemotherapy or radiotherapy and the owners decided skin expanders would offer the best chance for Tiger.

A number of tissue expanders are available on the market. Traditional Radovan expanders consist of a silicon balloon with an external filling port and require repeated hospital visits for saline to be injected into the port to increase the balloon volume to stretch the skin.

More recently, the advent of self-inflating expanders has occurred, which have a 14-day expansion profile where they absorb tissue fluid to increase to approximately three times their initial height.

Unlike traditional tissue expanders, there isno need for filling ports and the pressure exerted on the skin is gradual, rather than the step-wise expansion profile developed from manual filling.

In this case, self-inflating expanders were used for Tiger.

Tiger was anaesthetised, and the area around the mass clipped and prepared in a routine fashion. An incision was made along the left dorsal lip margin, and the skin and SC tissue were undermined with blunt and sharp dissection caudodorsally, to the level of the dorsal aspect of the nasal bone and just caudal to the centre of the zygomatic arch.

This dissection created a SC pocket to enable implantation of the expanders (Figure 3). A round expander 27mm in diameter and 5mm in height was placed on the most dorsal aspect of the nose, just caudal to the mass (Figure 4). Two expanders 27mm in diameter and 9mm in height were placed along the level of the maxilla through the same incision (Figure 5).

All expanders were held in place by non-absorbable, quilting sutures ventral to their placement and the incisions closed in two layers with a monofilament suture material.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics and pain relief were administered perioperatively and a 10-day course of antibiotics was dispensed, together with an Elizabethan collar.

Postoperatively, Tiger was very comfortable and discharged the same day. He was monitored by his owners at home and seen again at the authors’ hospital six days later.

At this recheck (day six of expansion), Tiger was pain-free and happy, with the owners noting no distress or obvious discomfort from the expanders.

The quilting suture holding the dorsal most expander on the bridge of the nose had ruptured through the deep fascia causing the expander to slip laterally. This was not considered a problem, so the expander was left in place. All other expanders had remained in place and were expanding as expected.

Five days later (day 11 of expansion), Tiger was noted to be in some discomfort by the owners. Physical examination revealed him to be bright, alert and responsive, and no tenderness around the expanders could be detected, nor was there any evidence of infection, discharge or seroma formation.

A small area of trauma was found on the right buccal cavity, which was thought to be self-induced and not to be a problem with the expanders. Pain relief and antibiotics were continued until day 14 when mass excision, implant removal and reconstruction were scheduled (Figure 6).

At day 14, Tiger was anaesthetised and prepared for surgery in a routine fashion. The four tissue expanders were removed through an incision at the most caudal extent of the 2cm margin, before the MCT was removed. However, rostromedially the mass was found to have invaded the dorsolateral nasal cartilage (Figure 7). Complete excision would have involved removing the cartilaginous portion of his nose and Tiger’s owners had stated this was not a result they would entertain.

Therefore, the remainder of the mass was dissected off the cartilage with the knowledge it would recur. After dissection, gloves, gowns and kits were replaced to reduce the risk of iatrogenic seeding. An advancement flap was elevated caudally though blunt and sharp dissection, and the infraorbital nerve and associated vessels were transected to allow rostral advancement of the skin.

The expansion devices create a fibrous layer of tissue in the SC tissue as pressure is increased; this layer had to be scored lightly with a number 15 scalpel to release the skin further. The flap was advanced rostrally to cover the left dorsolateral portion of the defect and temporarily secured using a Backhaus towel clip (Figure 8).

The incision was closed in three layers of continuous monofilament suture material. The expanded skin on the right dorsolateral nose was also elevated and scored in a similar manner to the first part of the flap and advanced over the midline to close the dorsal and right lateral portion of the defect (Figure 9).

An active drain was placed and Tiger recovered smoothly from anaesthesia. He was discharged on the same day with an Elizabethan collar, analgesia (NSAIDs and opiates) and broad-spectrum antibiotics.

At postoperative check-up, six days later, the advancement flap showed no evidence of dehiscence, ischaemic necrosis or seroma formation (Figure 10). The drain had stopped collecting serous fluid two days prior, sowas removed.

At 14 days postoperative check-up, despite a slight left deviation of the planum nasale, the cosmetic outcome was good and Tiger’s owners were extremely pleased with the final result (Figure 11). He had full use of his nose and both lips, with a characteristic smirk on the left side as a memory of his world’s first surgery.

This case report is intended to demonstrate tissue expansion offers an alternative to other wound closure techniques and can provide a real opportunity to achieve primary wound closure where previously this would not have been possible. At present, its application has been proven in limbs and facial tissue, but it is likely novel uses for expansion will come to light in this rapidly evolving surgical field.

Despite requiring a delay in the ultimate reconstruction of the defect and the need for two surgeries, skin expanders can negate the cost of managing a wound by secondary intention and the discomfort this inevitably brings to patients.