2 Jan 2024

Fabio Sarcinelli, Jinjing He and Victoria Phillips discuss how repair of this valve compares as a treatment option for the disease in canines.

Image © veronika7833 / Adobe Stock

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common acquired cardiovascular disease in dogs1. It is estimated that 75% of canine cases of heart disease presented to primary care practices are associated with MMVD2.

When affected by MMVD, the valve apparatus undergoes progressive connective tissue weakening due to abnormal collagen organisation and glycosaminoglycan accumulation, a process known as myxomatous degeneration3. Distortion of the valve architecture and the corresponding chordae tendineae leads to systolic atrial displacement (prolapse) of the mitral leaflets and abnormal leaflets coaptation during ventricular systole. The end result of those changes is mitral valve insufficiency, leading to systolic backward flow from the left ventricle (LV) into the left atrium (LA)2.

Disease progression is variable, with some dogs having slow progression and never reaching the clinical stage, while in others it may be accelerated. With progression of the disease, the severity of mitral regurgitation (MR) volume worsens, causing a gradually increasing volume overload of the left heart with consequent cardiac remodelling and increased left heart filling pressure. If the disease is severe enough, MMVD can result in the development of clinical signs of left-sided congestive heart failure (CHF), mainly dyspnoea and tachypnoea secondary to pulmonary oedema. The latter is the primary consequence of backwards transmission of the high LA pressure within the pulmonary veins and capillaries1,3,4.

A staging system for diagnosis and treatment of MMVD has been suggested by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus panel in 20195. The four disease stages are summarised in Table 1.

| Table 2. Stages of myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) | |

|---|---|

| Stage A | Dogs are at higher-than-average risk for developing heart failure, but without any apparent structural abnormality (for example, no audible heart murmur) at the time of examination. For example, cavalier King Charles spaniels, hypertensive dogs, geriatric dogs. |

| Stage B | Dogs have structural abnormality (for example, the presence of a murmur) but have never had clinical signs of heart failure. Stage B1: asymptomatic dogs with mitral regurgitation (MR) caused by MMVD, but without significant related cardiac remodeling. Stage B2: asymptomatic dogs with MR severe enough to result in cardiac remodeling (left atrium and left ventricle enlargement; LA; LV) sufficient to recommend treatment before onset of clinical signs based on the indication reported in the EPIC study4. Dogs in this category should meet the criteria outlined below:

|

| Stage C | Dogs with MMVD that have experienced an episode of clinical heart failure (pulmonary congestion and oedema) and/or low output signs (for example, exercise intolerance, weakness, syncope) |

| Stage D | Dogs with MMVD that have clinical signs of failure refractory to standard treatment |

No medical therapy is currently known to inhibit or halt valvular degeneration; therefore, management of MMVD mainly focuses in improving quality of life, by prolonging the preclinical phase and by improving the clinical signs and the overall outcome5.

For dogs with stage A and B1 MMVD, no medical or dietary treatment has been proven to be beneficial in preventing disease progression or development of heart failure signs. On the other side, a large prospective placebo-controlled study4 showed a substantial clinical benefit associated with administration of pimobendan in dogs with stage B2 MMVD. This study confirmed pimobendan to be safe and well tolerated, and to result in prolongation of preclinical (asymptomatic) period by approximately 15 months4.

Once MMVD progresses to the clinical stage (heart failure), medical treatment aims to reduce the venous pressure (diuretic), maintaining adequate cardiac output (positive inotropes), reducing the cardiac workload and protecting the heart from negative long-term neurohormone effects (ace-inhibitors)5-6.

Hence, medical treatment remains the first-line treatment option for dogs affected by MMVD, and aims to alleviate the clinical signs and postpone the onset of CHF. However, the long-term prognosis remains poor for dogs affected by advanced preclinical or symptomatic disease since medical treatment cannot reverse the pathological changes of the mitral valve apparatus5-7.

In the past 20 years, surgical MV repair under cardiopulmonary bypass has been proposed as an attractive alternative to medical treatment for dogs with MMVD8-11, and is now recommended for clients who can afford and access this technique at the few centres demonstrating evidence of acceptably low complication rates and effective, durable results5.

Dogs undergoing this surgery are known to have remained free of diuretic-dependent CHF for periods of up to three years after repair8. However, the costs of the procedure, its invasive nature and the limited availability of centres performing this procedure worldwide makes this surgery not ideal for a large subpopulation of canine patients7.

In recent years, transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair (TEER) has been introduced in human medicine and has evolved as the predominant alternative non-surgical treatment option in people determined to be at prohibitive risk for surgical MV repair13. The concept of edge-to-edge mitral valve repair was first introduced as a surgical mitral repair technique by Alfieri et al13. With this technique, the free edges of opposing anterior and posterior mitral leaflets are sutured together at the point of the maximum mitral regurgitant jet, resulting in a double-orifice valve13. This technique has also been described as a possible surgical technique method to correct leaflet prolapse in canine patients8.

Following the concept of Alfieri’s edge-to-edge valve repair technique, multiple devices have been developed with the aim of transitioning to a less invasive, fully percutaneous, transvenous procedure, such as MitraClip (Abbott Vascular, US) and PASCAL (Edwards Lifesciences, US)12. Both those devices are delivered via minimally invasive procedure techniques that do not require extracorporeal circulation12. However, due to the device size, they are not available for use in canine patients. To apply a treatment effect similar to that provided in people by MitraClip and PASCAL devices, a novel TEER device that uses a hybrid, transapical approach, originally developed for human patients (ValveClamp; Hanyu Medical Technology, China) has now become available for dogs affected by MMVD (V-Clamp; Hongyu Medical Technology, Shanghai, China). A hybrid approach is a procedure that combines a conventional surgical procedure with an interventional procedure, such as the use of a catheter-based procedure guided by fluoroscopy or transesophageal echocardiography imaging7. Hence, hybrid technique does not require extracorporeal circulation and is less invasive than traditional open-heart surgery7.

Compared to open-heart mitral valve repair under cardiopulmonary bypass, TEER requires shorter surgical time. Postoperative recovery is more rapid and less postoperative management is required7. In human medicine, more than 45,000 patients have been treated with this approach and the data collected so far has proven TEER to be safe and beneficial in ameliorating clinical symptoms, reducing duration of hospitalisation and lowering mortality14. When compared with conservative medical therapy, TEER has been associated with a better survival rate at one-year follow-up15. Furthermore, the five-year result of the EVEREST II trial showed no difference in mortality and comparable symptomatic improvement between people undergoing surgical MV repair, replacement or TEER16.

An easy-to-operate TEER system, the ValveClamp was recently developed. The feasibility of the device has been initially tested in a porcine model where the technique was reported to be feasible and safe, with a success rate of more than 90%17. The feasibility and safety of this new device has also been demonstrated in human patients with severe degenerative mitral regurgitation17.

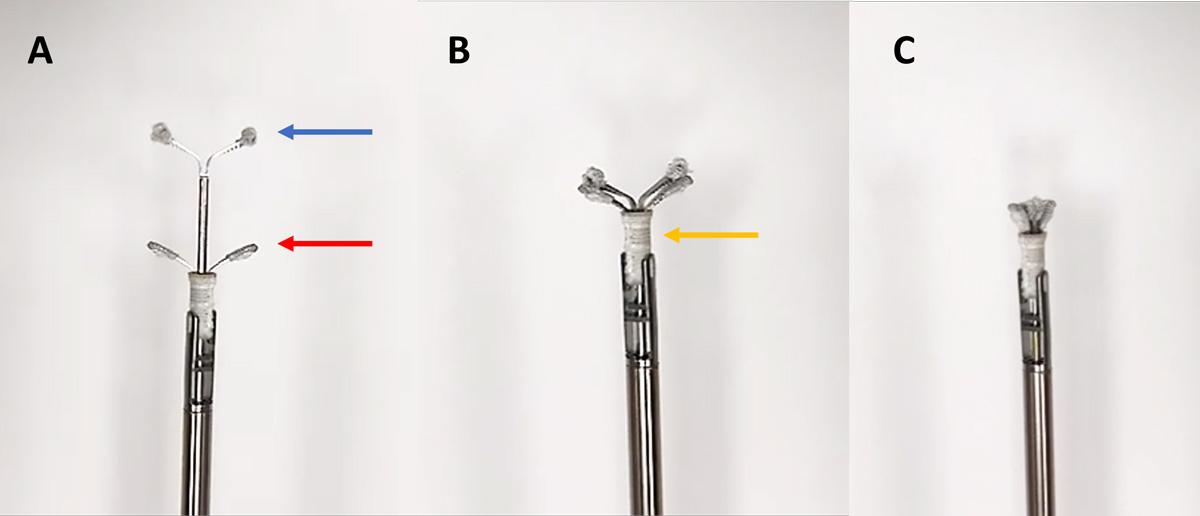

Taking the ValveClamp as a model, the V-Clamp system has recently been developed and is currently the only TEER device developed for treatment of MMVD in canine patients. This valve repair system consists of four devices: a clamp device; a valve-crossing device with a nitinol cylindrical mesh tip; a delivery system; and an introducer sheath17. The clamp device is composed of the parallel nitinol clamp arms (Figure 1a) and the closed ring (Figure 1b). The device comes in 4 sizes with widths of 14mm, 16mm, 18mm and 20mm.

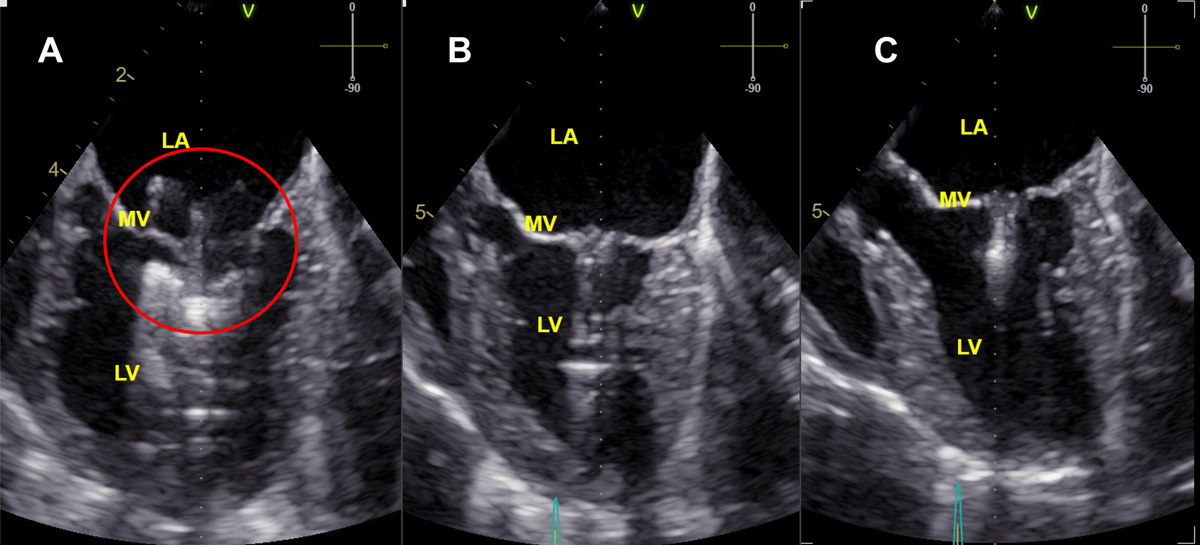

The procedure is performed under general anaesthesia. The patient is placed in right recumbency17-19. The TEER procedure is guided by a transoesophageal echocardiography and fluoroscopy. The heart is exposed at the fifth or sixth intercostal space via a small left-sided thoracotomy17-19. The pericardium is incised, and a purse string suture with non-absorbable suture material is placed on the cardiac apex17-19.

The apex is punctured, and the introducer sheath is delivered into the left ventricle. The valve-crossing device is inserted through the sheath into the left ventricle, and then both the sheath and valve-crossing device are advanced across the MV into the left atrium. The valve-crossing device is withdrawn. The delivery system loaded with the clamp is fed into the sheath and advanced into the left atrium. The position of the clamp is adjusted into the centre of the MV. The delivery system is then withdrawn slowly so the front clamp is exteriorised into the left atrium, and the rear clamp is in the left ventricle. The leaflets of mitral valve are captured within the clamps. The closed ring is moved forward and sleeved outside the periphery of the clamp so the clamping arms can close toward the central line and the clamping is tighter11.

If the clamping is not satisfactory, the closed ring can be reversed and steps can be repeated. The clamp is deployed after the position is confirmed on echocardiography and fluoroscopy (Figure 2).

The delivery system is then released, and both the introducer sheath and the delivery system are removed. The cardiac apex is sutured by the purse string. The thoracic wall and skin can be closed routinely. Heparinised saline is tapered off during recovery17-18. Postoperatively, the patient is medicated with analgesia and anticoagulant (for example, clopidogrel for a total of two to three months) and discharge is usually arranged 24 to 48 hours post-procedure.

Studies on the use of TEER devices in dogs with MMVD are limited, and long-term clinical outcome is yet unknown. A preliminary study assessing the outcome of eight dogs with naturally occurring stage B1 MMVD undergoing TEER with the V-Clamp device has recently been published18.

The study reported 100% procedural success and reduction of MR based on reduced regurgitant jet area, with 87.5% of dogs showing no detectable mitral valve regurgitation, and no audible heart murmur at three-month post-procedure in all dogs18. Moreover, no secondary mitral stenosis has been reported following this procedure18.

Those preliminary findings are supported by the results of early clinical experience at institutions where this procedure has been performed on a larger number of cases. Those data have shown TEER with the V-Clamp to be associated with low risk and high procedural success in dogs with severe MR, resulting in meaningful reductions in MR severity19. Moreover, early experience seems to suggest that dogs with earlier stage disease (B2, early C) might experience a greater reduction in MR severity and more reverse cardiac remodelling compared with dogs affected by more advanced stage of the disease (late C, D)19. A benefit on survival in dogs with severe MR has not yet been demonstrated.

Appropriate mitral anatomy for an edge-to-edge procedure is an important criterion for case selection, including the following factors: severe mitral regurgitation (regurgitant fraction ≥ 50%); A2-P2 leaflet’s segment prolapse, mitral valve anterior-posterior annulus diameter ≥13mm; coaptation gap between 2mm to 4mm; absence of mitral stenosis and/or cleft19.

MMVD is a common cardiac disease in dogs – especially small breeds – and medical treatment remains a first-line treatment option in general practice. In comparison to conventional open-heart MV repair under cardiopulmonary bypass, transcatheter edge-to-edge MV repair with the novel V-Clamp device is less invasive and less time consuming, and is associated with a shorter recovery time.

The short-term clinical outcome with TEER has been excellent based on currently available data18-19. Long-term prognosis and complications are yet unknown, and more studies are needed in the future.

Willows Veterinary Centre and Referral Service, in Solihull, is at the time of writing the only centre in UK, and one of the few in Europe, to offer this procedure.