23 Feb 2021

Guillaume Albertini DVM, MRCVS and Fabio Stabile DVM, PhD, DipECVN, MRCVS detail the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this common primary brain tumour occurring in older cats.

Figure 1. Abnormal gait and posture are common features of patients affected by intracranial disease, such as pleurothotonus.

Feline intracranial meningioma is the most common primary brain tumour in older cats. Clinical signs associated with intracranial meningiomas are generally slowly progressive and depend on the growth rate of the meningioma. A full work-up to achieve a presumptive diagnosis includes a general and neurological examination, serum biochemistry, haematology, urinalysis and advanced imaging techniques (MRI).

Definitive diagnosis can only be reached by performing histological analysis of the mass. Treatment options are divided into palliative, surgical, radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatments. Recent studies on radiotherapy protocols offer new perspectives for improvement in prognosis. Surgical treatment (debulking of the mass) is currently the treatment option associated with the best long-term prognosis. Surgical treatment also allows for a definitive diagnosis to be established.

Flash is 13-year-old male neutered domestic longhair cat that was presented for investigations of a three-week history of circling to the left and a suspected epileptic seizure. General examination revealed a grade II/VI left-sided heart murmur without clinical repercussions.

Neurological examination revealed a quiet mentation, left-sided circling and left pleurothotonus, lack of general proprioception on the right limbs and lack of menace response on the right eye (hemi-inattention syndrome) consistent with a left forebrain neurolocalisation. Based on signalment, history and neurological examination, an intracranial neoplastic disease was the main differential diagnosis.

Haematology serum biochemistry and urinalysis were consistent with a stage II International Renal Interest Society chronic kidney disease (CKD). MRI of the brain revealed a large intracranial neoplasia in the region of the left occipital lobe, left caudal part of the parietal lobe and left temporal consistent with a meningioma.

Screening of the patient for disseminated neoplasia (chest radiographs and abdominal ultrasound) revealed chronic kidney changes compatible with the suspected CKD and enlarged lymph nodes. Fine needle aspiration and cytology of the lymph nodes did not reveal metastatic infiltration.

After initiation of medical management (levetiracetam 22.2mg/kg/8 hours and prednisolone 0.9mg/kg/24 hours then decrease to 0.45mg/kg/24 hours after one week), surgical debulking of the mass was performed via a lateral rostrotentorial partial craniectomy. Histological analysis was consistent with a psammomatous meningioma.

The patient recovered uneventfully from the surgery and was discharged two days after surgery into his owner’s care. Two weeks after surgery, the patient had a normal neurological examination and no epileptic seizures were reported. The owner reported a dramatic improvement in Flash’s behaviour and could now notice “how much he had gradually changed”.

This introduction describes a successful surgically treated case of feline intracranial meningioma. The purpose of this review is to raise the awareness on the signalment, clinical signs, diagnostic test needed to diagnose intracranial meningiomas, and their treatment options and prognosis in cats.

Intracranial meningiomas are the most frequent intracranial neoplasia reported in older cats. They are often associated with a plethora of neurological signs. Due to progress in the past decades, intracranial meningiomas can be removed surgically, with a reported success rate of up to 90% and good-to-excellent long-term prognosis1-4.

Feline meningiomas are considered histologically and clinically benign, slow-growing, mostly solitary tumours arising from the arachnoid cells of the meninges5. Malignant meningiomas in the cat are rarely recognised and not well described2,6.

Intracranial meningioma is the most common primary brain tumour in cats, accounting for 56% to 58% of feline primary brain tumours1,2,7.

Other common feline primary intracranial neoplasia include astrocytoma (2.8%) and oligodendroglioma (2.6%). The most common secondary intracranial tumour in cats are lymphoma (14.4%) and pituitary tumours (8.8%)2,6.

Although most of the cats diagnosed with intracranial meningiomas display neurological signs, incidental meningiomas could be identified in 18% of cats undergoing a comprehensive necropsy investigation unrelated to a neurological condition1,7.

Domestic shorthair cats appear to be the most frequently affected breed. The reported mean age at diagnosis of intracranial meningioma in cats is 12 years1,8. No sex predilection has been demonstrated2.

Onset of neurological signs is generally slowly progressive and depends on the growth rate, location of the meningioma and secondary effects associated with the mass lesion (oedema, brain herniation, increased intracranial pressure)1,2,9.

The most frequent reported clinical sign in cats with meningioma is altered mentation (gradually becoming quieter, less interactive with the owner or the environment, becoming less active)2,5.

Epileptic seizures is also frequently reported, occurring in 14% to 25% of cases1,2.

Patients affected by intracranial disease can display compulsive behaviour, such as circling towards one side, pacing (walking without aim) and head pressing (pressing the head against a wall or a stationary object)1,2,9,10. Abnormal gait and posture are also common features, such as pleurothotonus (body turned to one side; Figure 1) and ataxia (lack of coordination)1,2,9,10.

Depending on the position of the mass lesion and its secondary effect on the brain, a plethora of other clinical signs – such as blindness – could also be noticed. Non-specific clinical signs (inappetence or anorexia) have been found in 21.5% of cats1,2,4.

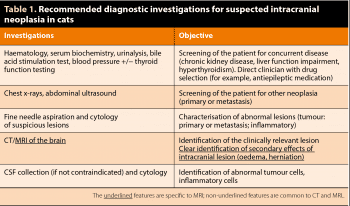

Diagnostic investigation recommended in cases of suspected intracranial neoplasia are summarised in Table 1. Haematology, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, advanced brain imaging – ideally via MRI – and CSF analysis are among those necessary for a diagnosis.

Screening of the patient (thoracic radiography and abdominal ultrasound) will aim at investigating any concurrent or associated extracranial disease, including primary and metastatic neoplasia2,5,11. If a lesion or suspected metastatic lymph node are identified during screening, fine needle aspirate, cytology, biopsy and histology should be performed2.

Although no association exists between changes in haematology, serum biochemistry and urinalysis parameters with intracranial meningiomas1,2,5,10, cats presented for suspected intracranial neoplasia are usually geriatric patients (commonly older than 12 years of age) and should be assessed for concurrent or related diseases (kidney disease, thyroid disorders).

CKD is the most common metabolic disease of domesticated cats12. Estimates of the prevalence of CKD in geriatric cats have ranged from 35% to 81%12.

Hyperthyroidism and CKD are common diseases in the geriatric feline population13. Prevalence of hyperthyroidism in a population of cats older than nine years of age was reported to be 6%13 and the overall prevalence of concurrent azotaemia and hyperthyroidism in cats has been reported to range from 10% to 23%13.

Meningiomas are extra-axial CNS tumours originating from the meningeal sheath surrounding the brain parenchyma. Most of the meningiomas are supratentorial (92%). Common locations include the supratentorial meninges, the tela choroidea of the third ventricle and, rarely, the cerebellar meninges1,2,14,15. Feline multiple meningioma occurs in approximately 17% of meningioma cases16,17.

Intratumoural mineralisation and haemorrhage are common features, and appear hyperattenuating (white) on CT images. Following contrast medium, intracranial meningioma appears contrast enhancing5.

With the advent of MRI, the ability to detect intracranial neoplasia has dramatically improved. MRI can often provide a relatively accurate presumptive diagnosis.

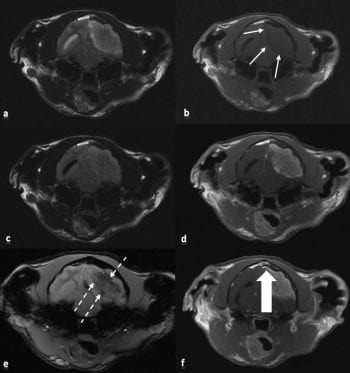

Meningioma has been correctly diagnosed based on MRI findings in 95% of cats with histologically confirmed intracranial tumours2,5,10,19. However, despite MRI’s high sensitivity (96%), MRI features do not allow prediction of tumour subtype and grade, and definitive antemortem diagnosis of intracranial meningioma requires histological examination. MRI features of meningioma in cats are well described and are summarised in Table 22,10,19,20 (Figure 2).

One of the most reported MR features of intracranial meningioma is the “dural tail” (Figure 2)1,2,5,15,17. After the IV administration of contrast medium, a linear enhancement of thickened dura mater may be continuous to the extra-axial mass2,19. This feature, though, can also be noticed in other tumour types affecting the meninges, including disseminated histiocytic sarcoma, lymphoma, granular cell tumour and metastatic disease (meningeal carcinomatosis)16,21.

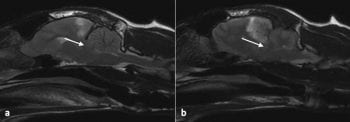

Intracranial meningiomas are commonly associated with concurrent peritumoural brain oedema and mass effect, ranging from midline shift to brain herniation1,2,5,14,16. In the rostrotentorial fossa, the most common herniation type is herniation of parahippocampal gyrus under the tentorial bone (caudal transtentorial herniation; Figure 3)5. In the caudal fossa, the most common herniation is herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum5.

CSF tap should not be attempted in patients with clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP; such as altered mentation, bradycardia or systemic hypertension) or in patients showing MR features of haemorrhage, severe mass effect and brain herniation5.

Attempting CSF collection in these patients may trigger intracranial haemorrhage, herniation and/or brainstem (atlanto‑occipital collection) trauma due to needle puncture5. When safe to perform CSF collection, site of collection should be the closest possible to the lesion. For intracranial meningioma, the privileged site of collection is the atlanto-occipital cisterna.

CSF analysis is neither a sensitive nor a specific investigation test for the diagnosis of feline meningiomas. Total nucleated count is usually in the normal range values (less than five cells/microL) and intracranial meningiomas rarely shed cells in the CSF1,2.

Albuminocytological dissociation (increased concentration of protein in CSF with normal nucleated cell count) is found in 30% of cases, but does not constitute a pathognomonic feature of feline meningioma2. It occurs with various diseases that alter the blood-brain barrier and allow protein from the blood to enter the CNS, increase the production of protein in the CNS or obstruct the flow of CSF.

Treatment of intracranial meningiomas can be divided into palliative (corticosteroids, antiepileptic medications) and curative (surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy).

The aim of palliative treatment is to alleviate clinical signs by minimising the secondary effects of the intracranial neoplasia (mainly oedema).

Prednisolone (0.5mg/kg/24h to 1mg/kg/24h orally) may be effective at reducing endothelial permeability, oedema and CSF production1,2. If improvement is observed, the dosage may be gradually reduced to the lowest effective dosage to control neurological signs.

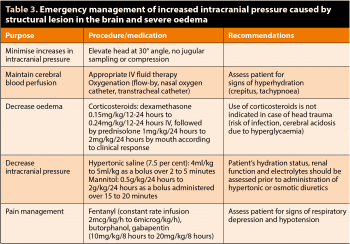

In patients with suspected or confirmed increased ICP, emergency administration of IV corticosteroids, mannitol or hypertonic saline can be also effective in rapidly reducing oedema, decreasing CSF production and stabilising the endothelial membrane1,2. Table 3 summarises medical management of increased ICP.

Antiepileptic treatment should be instituted in all animals with epileptic seizures caused by intracranial neoplasia2,5. The choice of antiepileptic medication is affected by many variables, including severity and frequency of epileptic seizures, presence and degree of neurological deficits (for example, decreased mental status, ataxia), hepatic and renal function, interaction with other medication, owner lifestyle and costs2,5.

Phenobarbital 2mg/kg/12h or levetiracetam 20mg/kg/8h to 30mg/kg/8h are safe and effective for the treatment of epileptic seizure in cats. Reported median survival time for cats receiving palliative pharmacological treatment for intracranial meningioma is 18 days (0 to 2.5 years)1,2,16,20.

Limited information exists on the use of chemotherapy for primary brain tumours in cats. Chemotherapeutic agents commonly used in meningiomas are hydroxyurea and lomustine2.

Hydroxyurea is an antimetabolite that specifically affects the S stage of the cell cycle. It inhibits the growth of tumours with low mitotic indices (such as meningiomas). Hydroxyurea (30mg/kg to 50mg/kg three days a week) showed in-vitro evidence of slowing down or arresting feline meningioma cells multiplication2 and did not show adverse effects in cats2. However, further clinical application is still required.

Lomustine (50mg/m2 to 80 mg/m2 of body surface area at intervals of six to eight weeks) is an alkylating antineoplastic agent belonging to the nitrosourea group. Efficacy and toxicity have been described in dogs, but no studies are reported in cats2.

Information on survival times following radiation therapy of feline meningiomas is limited, probably because of success reported with standard surgery alone. Indications for radiotherapy are incomplete surgical resection and the intracranial tumour is not surgically accessible2,22.

A 2018 retrospective study evaluating the effect of radiation therapy for intracranial tumours in cats with neurological signs (such as altered mentation, epileptic seizures and ataxia) showed improvement in almost all of the cases after radiotherapy8. More than half of the patients treated did not show any deterioration one year after treatment.

The study revealed a median overall survival time of 515 days (ranging from 66 days to 964 days)8. Brain tumour type (meningioma, pituitary tumour, choroid plexus tumour, glioma) and location did not seem to influence overall median survival time. Therefore, meningioma was not considered a favourable diagnosis compared to other feline intracranial tumours8.

This study opens new perspectives regarding radiotherapy treatment for feline intracranial neoplasia – especially for patients with inoperable neoplasia or estimated high perioperative and postoperative risks8. Further investigations will be required to identify which brain tumours are more likely to respond to radiotherapy treatment.

Histologically and macroscopically, feline meningiomas are commonly well encapsulated and easily delineated from normal brain, and complete surgical resection can be achieved.

Surgical removal of feline intracranial meningioma bears specific surgical and anaesthetic considerations5. Lateral rostrotentorial craniotomy/craniectomy is the standard procedure to access tumours of rostral cranial fossa. Postoperative mortality associated with craniotomy for meningioma removal in cats ranges from 12% to 19%1,2,3,4,10.

The most common causes of perioperative mortality are bleeding, transcalvarian herniation (brain herniation through the craniectomy site), ischaemic lesions and increased ICP (mainly due to oedema). Reported median survival times following resection of a single or multiple meningioma ranges from 21.7 to 37 months1,2,3,4,10 and multiple meningiomas identified on MRI do not worsen prognosis2. However, meningiomas of the caudal fossa bear a poorer prognosis as surgical procedures are less described and are associated with higher risks of comorbidities1,2,10.

New surgical descriptions associated with fewer comorbidities have been recently published in a case report22, but further clinical studies are required.

Postoperative recurrence of feline meningioma has been reported in about 20% of cases and a large study has reported a median time to tumour recurrence of 9.5 months after the surgery1. Repeated surgery and/or radiotherapy may be successful in treating intracranial meningioma recurrence in cats2.

Medical management (as described in the palliative treatment section) should be continued after surgical removal of the mass.

Intracranial meningioma is the most common brain tumour in cats. MRI is currently the most sensitive and specific non-invasive investigation, and allows precise measurements to plan surgery.

With palliative treatment only, prognosis is poor. However, prognosis is significantly improved by surgical debulking of the mass. Craniectomy and mass debulking also allow to reach definitive diagnostic via histological analysis of the mass.

Due to the good-to-excellent prognosis of surgical treatment, other therapeutic options (radiotherapy, chemotherapy) are less described and long-term prognosis cannot be fairly compared to surgical resection of feline intracranial meningioma.