28 Jan 2025

Pippa Elliott BVMS, MRCVS turns the clock back a century to show the issues women faced in trying to enter the profession.

“One hears a great deal of talk nowadays, about careers for women… [give] thought to the possibilities of being either a kennel maid or a lady vet.” Yorkshire Post, 10 July 1925.

One hundred years ago, in 1925, Gerald Durrell, Honor Blackman and Margaret Thatcher were born; F Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby; and George Bernard Shaw was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. The country had come through the Great War and society was changing because women had participated in the war effort, and proved their worth outside the home.

The perceived order of things had been shaken, and now women could strive to have a career.

One hundred years later, safely in 2025, you may shrug your shoulders and say, “So what?” But back in 1925, the changing roles that women demanded was seismic. This is arguably no better illustrated than in the veterinary profession.

“In the world as it is today, [a woman being] mere decoration doesn’t count for very much.” The Bystander, 18 February 1925.

To put this in context, when the 19th century ended, women and men were expected to inhabit separate spheres; the women’s sphere was the home and raising the next generation, while the men’s world was work, career and telling women what to do.

Think about it: a change of attitude from womanly domestication to career woman, in the same span of years that we’ve gone from the Millennium bug to Trump’s second presidential term (okay, plenty of groundwork had been done in the 19th century by the Suffragists, Suffragettes, and various New Women, but you get the picture).

“[Profound] difference in the position and outlook of women… disturbingly different to the older generation.” The Bystander, 11 February 1925, writing about post-First World War women.

So, in the brave new world of 1925, how did women fare? How many RCVS-accredited female veterinarians were there? Ahem, just two: Aleen Cust (graduated December 1922) and Edith Knight (graduated December 1923). Indeed, in 1924 and 1925, no new female graduate veterinarians were recorded (David Plant, archivist, RCVS Knowledge).

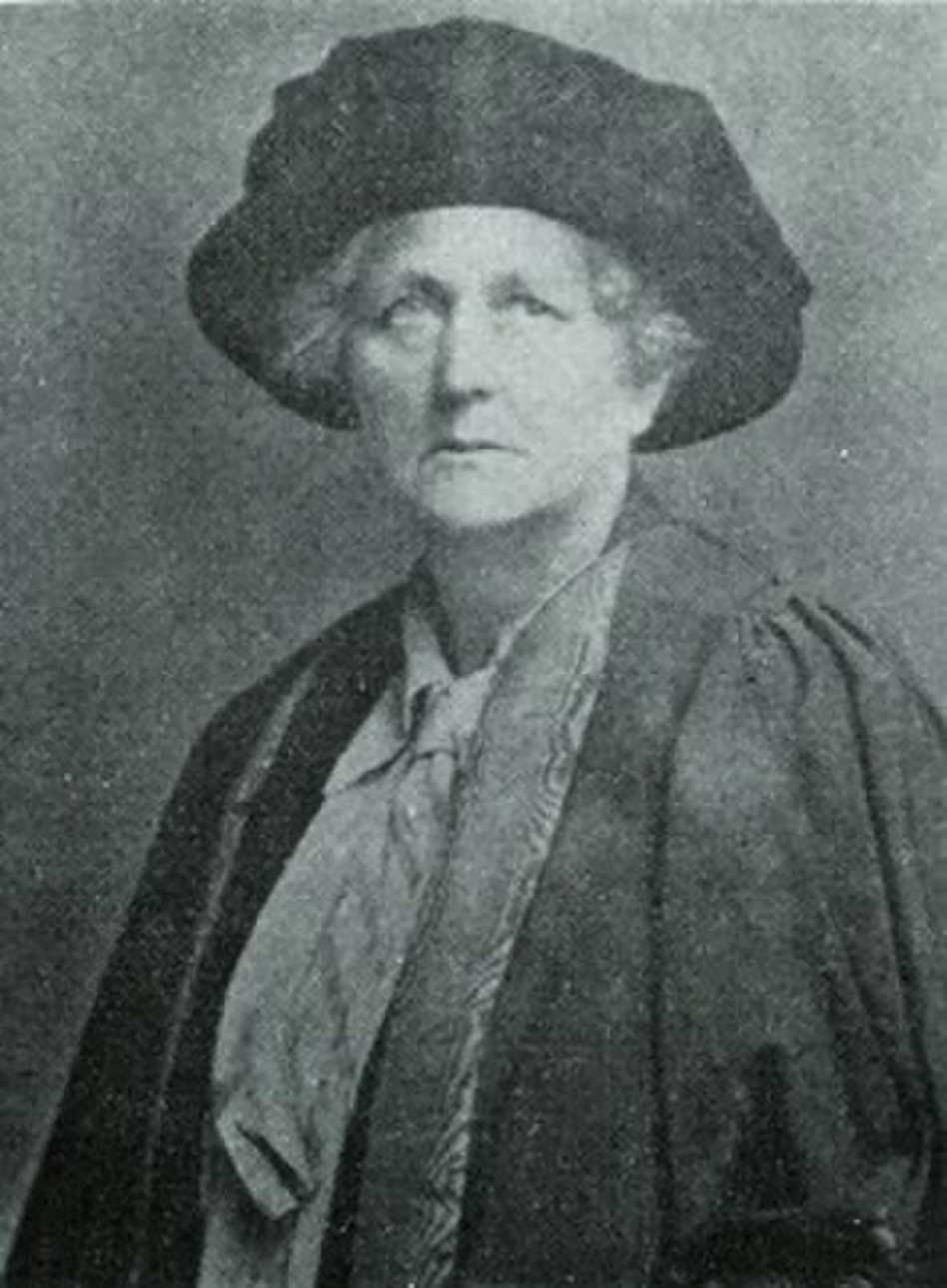

Miss Cust was quite a character: an aristocrat, the sister of the King’s Equerry, Charles Cust, and daughter of Sir Leopold Cust. She was horse-mad, bred dogs (pocket cocker spaniels) and generally knew she was just as capable as any man, and had set her heart on becoming a vet.

The only problem was that, prior to 1919, the RCVS charter did not permit the admission of women to the membership. But Miss Cust was not a woman to be deterred. She enrolled at New Veterinary College in Edinburgh under the male name of Arno Custance, and proved to be an excellent student, winning honours and medals. She completed her Edinburgh studies in 1897, but had a dilemma: she had the knowledge, but not the mandate to practise veterinary science, because the RCVS prohibited women sitting the exam necessary to practise in England.

Miss Cust’s solution was to evade the RCVS’ censure by working in Ireland (a vet practice in Roscommon) and not using the MRCVS title. Her arrival at Roscommon “caused consternation and scandalised the local priesthood”; however, her skills won out in the end.

Then, during the First World War, she worked in France to identify the bacterial agent responsible for a high mortality rate among British horses.

Scroll back slightly to 1919, and the crucial Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919. This basically whipped the rug out from under the argument that the RCVS charter could not permit women to register.

Who was the first woman to sit the exam? You guessed it: Miss Cust (and given her two decades of practical expertise, she was allowed to sit the final exam only, rather than complete the whole course).

Then, on 21 December 1922, she became the first woman to part with the registration fee of one guinea (equivalent to £44 today) and legally use the title “veterinary surgeon, MRCVS.” Her registration number? 1,501.

Where Miss Cust led, other women wanted to follow and aspired to become veterinary surgeons. But despite Aleen making a success of farm and horse work in Roscommon, even she had doubts about the fitness of women for large animal work. She gave an interview to the Daily Express, which was widely reprinted: “[Women should] consider bacteriological research… field wide open to females to specialise in disease of pets and smaller animals.” Larne Times, 10 January 1925.

This reflected a widely held view: “The veterinary care of cattle and horses does present severe difficulties for women. Not so the treatment of dogs, cats, birds [and so on].” Meath Herald, 26 December 1925.

Even the progressive Miss Cust thought she was the exception rather than the rule: “To deal with cattle and horses required considerable physical strength, and although Miss Cust has treated them for every possible physical ailment, it would, she considers, be beyond most women’s powers.” Meath Herald, 26 December 1925.

In fairness, Miss Cust tried to turn a weakness into a strength by saying: “With pet dogs and cats… operations when necessary, require a lightness of touch more than strength and such animals will make friends with a woman and let her do anything for them, when they will have nothing to do with a man.” Meath Herald, December 26 1925.

Miss Cust also had an eye for the future of veterinary practice: “Whilst horse practice is decreasing, dog practice is growing. In the latter branch, and also in cat, goat and poultry work, there is a big field for the woman veterinary surgeon.” Yorkshire Evening Post, December 22 1922.

In the 1920s, The Bystander was a popular weekly magazine. It published cartoons, short stories, opinion pieces, and reviews. Some big names were featured, including illustrations by W Heath Robinson, and stories by Daphne Du Maurier. A regular columnist went by the name of “The Kennelman” and – you guessed correctly – he wrote on the popular topic of dogs.

The Kennelman wrote about female veterinarians several times in 1925 and had some good ideas; for example, he suggested the RCVS should offer a new diploma and degree, exclusively for the study of canines and felines – his argument was that cats and dogs were becoming a large and important part of veterinary practice, and it would be reassuring to the owner if treatment was administered by someone with a special diploma.

He also opined that women were ideal to take on that training: “It is safe to say that in the army of dog breeders and exhibitors in Britain consist of women. Many of them are ably qualified for and strongly drawn to dog doctoring, but have no ambition in the direction of farm or stable surgery.” The Bystander, 30 December 1925.

The Kennelman also suggested that suitable careers for women were either as a female vet or kennel maid. In fairness, I believe his intention was to point out an alternative career route for those without the funds to finance an expensive degree, it being no coincidence that the first female RCVS-registered vet came from a wealthy family. The training was expensive: “Owners of kennels would welcome a really intelligent, trustworthy girl who was keen about the work.” Yorkshire Post, 10 July 1925.

As an aside, the indomitable Miss Cust also made the news in 1925 for reasons other than her professional career. She was an avid breeder of pocket cocker spaniels. Her dogs were admitted to a class at Crufts in 1925, which caused consternation among purist cocker breeders.

Breeders argued that the “Lilliputian” cocker could not be pure cocker blood and, therefore, should be excluded. Miss Cust insisted her tiny cockers were true blood, as she selected only the “little Joeys” [smallest pup in the litter] from purebred parents to breed for the next generation, and gave as evidence that her pocket cockers regularly went rabbiting.

Out of interest, how did the RCVS rank in the timeline of the official admission of women to the veterinary profession?

But before we congratulate ourselves for being on the ball in Europe, it was Poland (1889) and Ukraine (1896) which were the first to admit women to the veterinary profession.

From 2025, looking back to 1925 and reflecting on the difference 100 years makes, it is interesting to ponder what the profession might look like in the next century, in 2125. Predictions, anyone?