24 Feb 2025

Rory Thomson BVMS, MRCVS considers how veterinary diagnoses are made as opposed to those in human medicine.

A one-year-old female Labrador retriever is presented to a first opinion practice with a cough of 10-day duration. NSAIDs, paracetamol and anti-histamines had been used appropriately (although without veterinary advice) for symptomatic treatment without any improvement.

The dog is fully insured, with no exclusions or financial constraints from the owner. The dog is eating and drinking normally, with no exercise intolerance. The cough is persistent, with approximately three to four episodes every minute including through the night, whereby the dog is unable to rest.

Three months previously, a chest infection was diagnosed based on an abnormal thoracic auscultation and treated with a seven-day course of prednisolone at 1mg/kg once daily and amoxicillin 10mg/kg every eight hours. The dog has a suspicion of underlying inflammatory airway disease and tested positive for house dust mites on a blood allergy test one month previously, and has been on a topical, inhalational corticosteroid administered via a spacer chamber.

Clinical exam reveals a normal mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time. No abnormalities were identified on chest auscultation, although an intermittent dry cough is present on clinical examination. Pulse oximetry is unremarkable and temperature is normal. A seven-day course of prednisolone at 1mg/kg is prescribed and advised to start if the cough is not improving.

The prednisolone is started two days after the initial consultation due to the cough getting worse. Within 24 hours of starting the prednisolone, the persistent cough becomes more intermittent; however, more severe paroxysmal coughing episodes occur approximately three times daily, with the dog being clinically normal between the episodes. During the paroxysmal coughing episodes, cyanosis was reported on one occasion, and regular vomiting occurs during or shortly after the episodes.

The dog was reassessed at the end of the seven-day prednisolone course. The cough had become more productive, yet the coughing episodes were still occurring three times daily – but starting to improve. The prednisolone was discontinued and the owner advised to reassess if the cough deteriorated. A referral was made; however, due to staff holidays, the earliest the dog could be assessed at the referral centre was five weeks later. The cough deteriorated within 48 hours of prednisolone withdrawal and the dog presented to an out-of-hours clinic due to a bank holiday weekend.

Again, clinical exam was unremarkable other than the cough, which had become more dry again. Pulse oximetry was unremarkable, chest auscultation was unremarkable and temperature was normal.

A presumed diagnosis of mycoplasma was made and a three-day course of azithromycin started. It was recommended if no improvement was made in three days to review at the primary care practice and start a longer corticosteroid course, but only consider investigations if the cough had been present for over six weeks.

The case report outlined is 100 per cent accurate with one small signalment change: this was not a one year old Labrador retriever, it was my 10-year-old daughter.

I am disappointed with the service my daughter has received from the NHS – especially given the high level of individually tailored care I strive to provide to my patients. I have private health insurance for my children; however, even when trying to pay for private medical treatment for my daughter, the earliest and closest appointment I could make with a respiratory paediatric doctor would be four weeks away and 100 miles from my home. This got me thinking not only about how quickly and efficiently we perform as a profession compared to our medical colleagues, but also about how we work our cases up – particularly when there are financial constraints.

At vet school, we are taught the textbook approach to investigating and approaching diseases. If this was a veterinary patient, we would also want a parasite treatment history. Our full diagnostic work-up may include:

Once we have all this information, we would consider therapeutic options. This is known as “gold standard” by some, and some younger graduates seem worried that by deviating from this gold standard they are open to professional negligence and litigation. A thorough work-up like this would be expensive and, arguably, excessive.

My experience has shown that our human medical colleagues are less inclined to investigate to get a definitive diagnosis when empirical treatment is likely to be of benefit. The “common things are common” approach to medicine seems to be applied much more readily in the human work-up, with a “presumed diagnosis” made on clinical signs and physical examination and if treatment is not successful investigations can be performed.

I find it interesting that for a respiratory issue, blood allergy testing (which seems very controversial in veterinary medicine) was performed first and our standard “baseline bloods and imaging”, which we are taught to do in pretty much every case, has not even been considered.

I believe the key to good veterinary practice is communication. I think this gold standard of care should be offered to clients, but a discussion including costs and potential consequences of the gold standard tests should be made with the owner, and options for a reasonable way forward presented to them in a way in that they can make an informed decision as to how to proceed.

I do believe that treatment should be tailored to the individual patient and owner, and in most cases, this gold standard is unnecessary both financially and clinically.

Historically, we could test for everything in case we miss something. With the increase in availability and variety of diagnostics available to us in first opinion veterinary practice, and the increasing costs associated with these advancing resources, I think we need to start taking a more balanced approach as to what we test for and when.

If this were a canine case, a high differential would possibly be Bordetella bronchiseptica (kennel cough). Symptomatic treatment would certainly be very reasonable initially, avoiding the use of antibiotics, as most cases will resolve without antibiotics. If the owner and dog were becoming distressed, and cyanosis was being reported, an empirical antibiotic choice without further investigation is certainly justified – especially if there are financial constraints.

I would opt to investigate a canine patient with these signs persisting for more than three weeks – especially if the owner and dog were clearly distressed, and finance was not an issue.

In the case of my daughter, I think it would be extreme to be expecting a full general anaesthetic and bronchiolar lavage to be performed, as the risks associated with that are unnecessary given the likely differential diagnoses.

I would, however, have thought a chest x-ray and possibly some swabs for culture would have been a viable option. It may not provide a definitive diagnosis, but it would certainly provide peace of mind that something more sinister was not underlying. It would also provide good disease surveillance, given that whooping cough (Bordetella pertussis) was a differential diagnosis of the GP and is a notifiable disease.

When I requested further investigations, I was told in a very belittling way: “We don’t have the resources to investigate every 10 year old with a cough.”

At least in veterinary medicine we would offer to investigate our patients if the client wanted to and it was justified. We should give ourselves a massive pat on the back for the level of service we provide, and because we do so with compassion and empathy.

Outcome for my daughter

The signalment is obviously very important when coming up with a differential diagnosis list. Reading through the clinical history in my case would be very fitting with “kennel cough” in a one-year-old Labrador retriever with a cough.

In humans, asthma and other infectious organisms may fit much higher on the differential list, which may warrant the different work-up pattern I have experienced.

I wrote the first part of this article shortly after a trip to the accident and emergency department with my daughter on a New Year’s Day. I have come back to it a few weeks later to draw a conclusion with an outcome and diagnosis for my daughter.

I subsequently did manage to get some further investigations done and achieve a definitive diagnosis of whooping cough through an oral fluid test from UK Health Security Agency (formerly Public Health England).

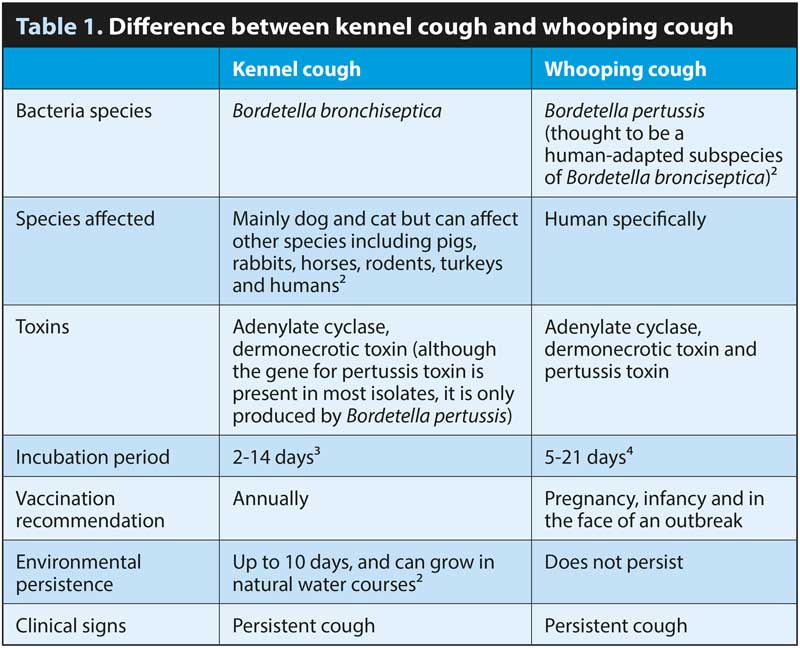

Whooping cough is more colloquially known as “the 100-day cough” or “pertussis”. It is caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, which is very similar to the organism B bronchiseptica, which is often implicated in canine infectious respiratory disease complex, colloquially known as “kennel cough”. Table 1 shows some of the similarities and differences between whooping cough and kennel cough.

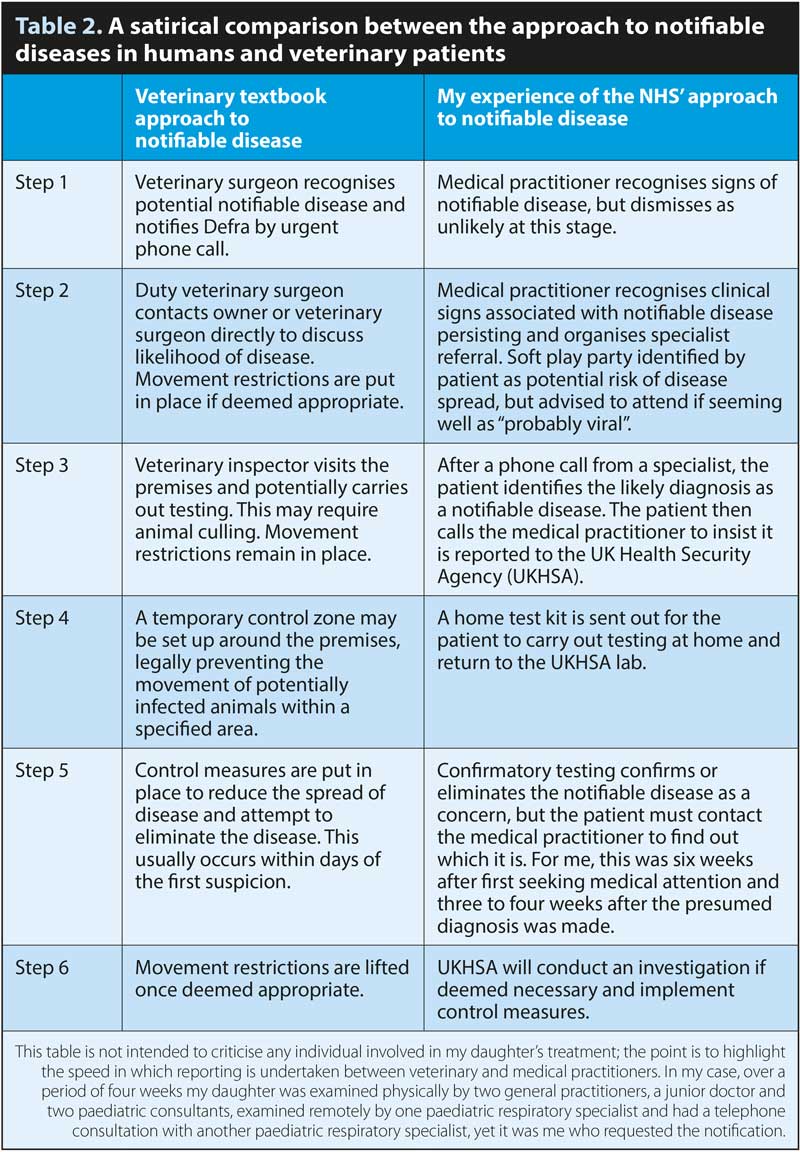

From my experience, there seems to be a slight variation between the human medical practitioner’s approach to legally notifiable diseases and the veterinary practitioner’s approach to notifiable diseases. I have summarised the difference in a somewhat satirical way based on my experience in Table 2.

From my experience, there seems to be a slight variation between the human medical practitioner’s approach to legally notifiable diseases and the veterinary practitioner’s approach to notifiable diseases. I have summarised the difference in a somewhat satirical way based on my experience in Table 2.

Interestingly, the incubation period of B pertussis can be as long as 21 days, so when my youngest daughter started showing similar, but milder clinical signs a fortnight later, I became strongly suspicious of infectious disease, and there are not many I could find with such a long incubation period with the same clinical signs.

While researching the possible causes of my daughter’s cough, I came across the medical brief about whooping cough for medical practitioners published by Public Health England. This described my daughter’s history exactly and clearly states that whooping cough should be suspected, and reported, for any case presenting with: “An acute cough lasting for 14 days or more without an apparent cause plus one or more of the following: paroxysms of coughing, post-tussive vomiting, inspiratory whoop”1.

I shall add here that the GP initially and reasonably believed the disease to be asthma-related. As my daughters were both vaccinated for whooping cough according to the NHS guidelines, the possibility of whooping cough was initially dismissed in favour of asthma.

My youngest daughter subsequently presenting with the same signs, which did go on to persist for longer than 14 days, does make the diagnosis and need to notify more obvious with hindsight.

Our knowledge of the licensed veterinary kennel cough vaccines for B bronchiseptica allows us to understand that immunity to this bacterial vaccine is not as strong as our typical viral vaccines.

Our knowledge of the licensed veterinary kennel cough vaccines for B bronchiseptica allows us to understand that immunity to this bacterial vaccine is not as strong as our typical viral vaccines.

The vaccinations are licensed to be given annually and the licences do not prevent disease; they only reduce clinical signs of upper respiratory tract disease and possibly bacterial shedding. As such, we often still see vaccinated dogs with clinical signs of “kennel cough”. Many licensed Bordetella species vaccinations are available for dogs. The human vaccine does appear to have a longer duration of activity; however, it has been shown that immunity will start to wane from about two to three years after the last booster given at three years and four months of age. This means that my six year old and 10 year old would still be susceptible to the disease.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, control measures in the form of mass testing with rapid results and movement restrictions were enforced on a national level to limit the spread of the novel infectious disease.

The degree of movement restrictions applied to farm animals during a notifiable outbreak is not feasible for humans; however, active promotion of some of the covid-19 recommendations for other notifiable diseases, such as whooping cough (for example, basic hygiene and self-isolation of infected individuals) along with more rapid recognition, must surely be more economical and save more lives in the long run that the current system?

The next part of this series will use my personal experience with my daughter to compare the human medical approach to chest radiography.

Rory Thomson graduated from the University of Glasgow veterinary school in 2009. In 2020, Rory became the owner of Roker Park Vets in Sunderland. Rory also trained as a veterinary marine mammal medic with British Divers Marine Life Rescue in 2007 and also acts as one of the veterinary advisors for Tynemouth Seal Hospital.

References