18 Mar 2025

Orly Simkin BVSC, PCEC, MRCVS provides concepts and ideas to help veterinary professionals understand what is happening when communication does not seem to be working…

Image: Rakchanok / Adobe Stock

The way we communicate has a huge impact on our colleagues, our clients, our patients and ourselves.

We are taught “clinical communication” when gathering a history or discussing our diagnostic plan during our clinical training. We might have some additional training on the job on communicating with each other to improve patient safety or communicating with clients to avoid complaints.

But have you ever wondered what it is that makes a conversation go differently to what you had expected? Have you ever felt put off by the tone of someone’s voice or their body language?

In this article, I offer some concepts and ideas that might help you understand what’s going on when communication doesn’t seem to be working and what could be tried instead.

Eric Berne developed his model of transactional analysis (TA) in the 1950s as a psychotherapeutic approach to explain how people make sense of themselves, their relationships with others and their context1,2.

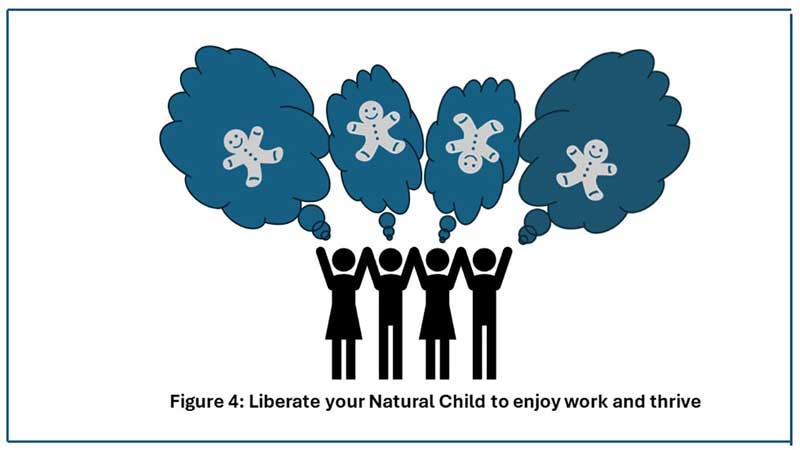

A detailed description of TA is beyond the scope of this article; however, the basic concept is that we all have three parts or “ego states” to our personalities: the parent, the child and the adult. (Figure 1).

TA is a method for understanding which of these egos the speaker is transmitting (or “transacting”) from and to – so that the receiver can respond more effectively3,4.

“The parent” ego state is created by observing and “recording” in our minds, the behaviours, opinions and attitudes of our parents and parent-figures. We create this ego from birth until we are about five years old, and we are not equipped to selectively filter what we record1.

The parent is made up of two parts: “the critical parent” and “the nurturing parent”.

The critical parent speaks a language of “shoulds” and “should nots”, “ought to”, “must”, “always”. This ego is judgemental and uncompromising – to others and to ourselves – and when overly harsh can lead to feelings of guilt, shame and depression.

The nurturing parent speaks a language of love and care, giving help and advice. This ego is protective of others and to ourselves – and when overly used can inadvertently lead to others feeling a reduced sense of self-confidence and self-efficacy.

“The child” is made up of two parts: “the natural (or free) child” and “the adapted child”1.

The natural child is creative, spontaneous and curious – and loves having fun. This ego brings joy to our lives. It also brings other feelings like fear and aggression. It expresses itself freely and demands instant gratification.

The adapted child has learned to behave in a way that is expected initially by its parents, then by society, peers and the work environment. It is compliant, accommodating and reserved. It can bring feelings of frustration, which may result in manipulative and rebellious behaviour.

The “adult” ego is grounded in the present. It is cool, calm and behaves rationally. It gathers information, processes it objectively and integrates this with the previous experiences of all three ego states to select the most appropriate response for the current realitysup>1.

Berne defined communication between people as “transactions” between their ego states.

Complementary transactions happen when the ego state that is addressed is the one that responds3,4 (Figure 2). This can take place between any ego state. As long as the response is coming from the expected ego, the communication continues effectively3,4.

For example, a senior vet might communicate in “nurturing parent” when mentoring a new graduate. The expectation is that the new graduate responds in “adapted child”. This might be an effective way to transfer information – and both vets might well benefit from this especially at the start of their relationship. However, over-reliance on their nurturing parent colleague, can have unintended consequences. What might happen if the new graduate finds themselves unexpectedly working in sole charge?

Another example might be a client complaining about the service they received in critical parent. If the practice manager responds in adapted child as the client expects, the client will probably feel satisfied this time. What might this mean for future interactions with this client? How might this affect their relationship with the clinical team?

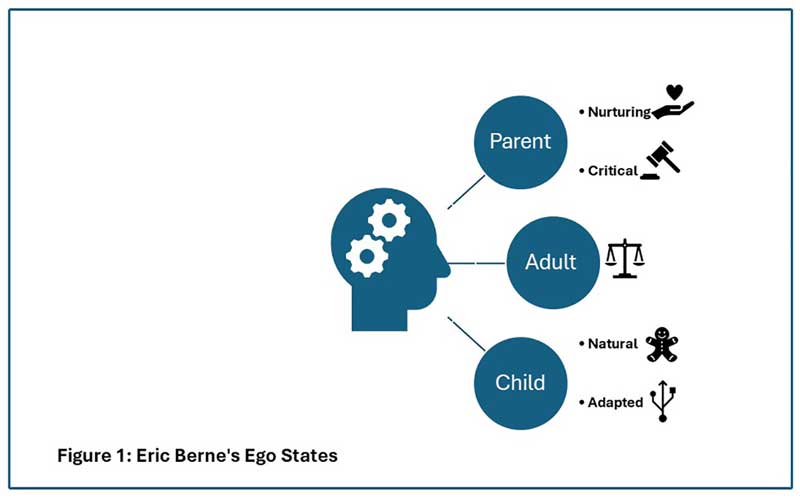

Crossed transactions happen when the response does not come from the ego state that the communicator was aiming at3,4. (Figure 3).

Crossed transactions can be unproductive if they result in closing down lines of communication3,4. So, in the aforementioned example, if the practice manager responds to the critical parent client in critical parent, they are likely to come to an impasse and further communication will not be possible.

When these situations arise, the unfortunate consequences tend to result in clients escalating their complaints – or airing their views on social media. The breakdown of trust that ensues then makes it impossible for the practice to continue to provide its services, and everyone loses.

Crossed transactions are effective, however, when they result in opening communication between different ego states3,4. Using the aforementioned example again, if the practice manager chooses to respond to the client in adult, they are inviting the client to also respond in adult and this is likely to de-escalate the situation, as both adult egos seek to resolve the issue together.

So, how can we keep our communication in adult – especially when we need to have a difficult conversation?

One way could be to use non-violent communication (NVC).

NVC was developed in the 1960s by Marshall B Rosenberg, a clinical psychologist. He originally used it as a tool to resolve conflict within American schools when they were racially desegregated at that time5. Since then, it has been used as a communication and mediation method in conflicts around the world6 and in our context, is being adapted as part of patient safety communication in human7 and veterinary8 medicine.

It is a way to help us connect with each other and with ourselves, so that our natural human compassion can flourish9.

Marshall described four components to communicating in this way: observations, feelings, needs and requests.

Here are the basics of the four steps:

Let’s look at each of these in a little more detail.

We often mix an observation with a judgement, an evaluation or an assumption. When we do this, we are communicating from parent and it is unlikely that our message will be heard as intended.

It can be difficult to separate what we see from what this observation makes us think – as this can happen almost automatically. So, for example, when you see the prep table hasn’t been cleaned, the adult observation is: “The prep table is not clean.” And not: “No one ever cleans the table, they’re all lazy.”

When describing what you see, focus on the specific time and context of what you see and avoid generalisations and evaluations. When people hear criticism, they either respond defensively in child or counter-attack in parent9.

We often describe thoughts instead of feelings, for example: “I feel like I am constantly on call,” – describes what the speaker is thinking – the use of the word “like” generally makes a feeling difficult to clearly understand9.

“I feel exhausted/frustrated/annoyed because I am constantly on call” would give the listener a clearer idea of the message the speaker is trying to convey.

We also often describe what we think we are, or what we think others think we are, instead of describing our feelings9.

For example: “I feel misunderstood at work.” This statement describes what the speaker thinks about how they are perceived by their work colleagues. This is an assumption and – even if it is correct – it will likely result in the listener hearing a judgement that will likely lead to a defensive response from their child.

Notice your response to this alternative: “I feel anxious at work because I think my colleagues misunderstand me.”

It is hard to communicate our feelings, because when we do, we show that we are vulnerable and yet, this vulnerability is what connects us as humans.

Other aspects that connect us all as humans are our common human needs.

These are physical and also intangible – like the need to be heard, the need to belong or the need to be respected9. Rosenberg believed that we choose to respond to what someone has communicated in certain ways, because of an unmet need.

So, when we receive a negative message from someone, we could receive it in child and blame ourselves. Alternatively, we could receive it in parent and blame the speaker.

The NVC approach is to receive it in adult by being aware of the feelings that are coming up for us and focusing on our needs and expectations that are giving rise to those feelings, in that moment9.

If we want our needs to be met, we need to express what they are – and how we do this is also hard. If we express our needs as an evaluation or judgement – we’re back to the parent. The listener will likely hear criticism and they will be back to their child responding in defence or their parent responding to counter-attack9.

The more directly we connect our feelings to our needs in adult, the easier we make it for the listener to respond in adult compassionately.

Here is an example: “I feel frustrated when you are late.”

Notice your response to this version of the same statement: “I feel frustrated when you are late because I want the ops to start on time so that our patients can have enough time to recover before they are discharged.”

Once we have communicated what we observed, what we felt and the unmet needs that led to these feelings, we can make a request of the listener, as an “Adult” to an “Adult”, to meet those needs9.

NVC suggests the conscious use of language that is positive, clear and actionable9.

Request what you would like someone to do, rather than what you don’t want them to do – the clearer you are about what you need, the more likely you are to get what you need.

Let’s look at this example: “I wish you would stop checking your work emails when you get home in the evenings.”

The listener might stop doing that – and check their social media feeds instead. If you wanted them to spend more time with you, you still haven’t got your needs met.

For NVC to be effective, the listener needs to receive what we ask for as a request, not a demand9.

By expressing the first three stages of the process, we share our vulnerability and humanity which is more likely to result in the listener receiving our message in adult and agreeing to the request out of empathy, rather than out of guilt, obligation or fear9.

So, if a head nurse notices the previous day’s in-patient forms were not completed, she could confront her team with the incomplete forms in critical parent saying something like: “Yesterday’s in-patient forms were not completed. This is not good enough – you must make sure these are completed.”

Or she could try: “I noticed yesterday’s in-patient forms were not completed. I felt worried when I saw this because I don’t know if the ops got pain relief before discharge. I want to feel confident that all our patients have had the pain relief they need. Please complete the in-patient forms whenever you administer meds or monitor our patients.”

Once we have made our request, we, as adults, need to accept that the listener has a choice in how they respond. We need to listen for what they might be observing, feeling and needing in response to our request so that the communication can continue effectively9.

In this way, NVC builds relationships where we can express ourselves honestly, without judgement – and receive messages from others empathically9.

The nature of our work in the veterinary world is often critical, carries significant risk and is unpredictable and in these situations, bringing our calm, rational adults to work is helpful and likely to improve our patients’ outcomes.

However, if we also want to enjoy what we do, motivate our colleagues, and appreciate new and creative ideas, we need to liberate our natural child (Figure 4)4.

It is our natural child who allows us to take pleasure in a job well done and to relax after a busy day.

When we give greater freedom to the positive qualities of our natural child, we can allow ourselves to let go a little, have some fun and thrive.