2 Oct 2017

John Carr and Mark Howells discuss three ideas for techniques to help enhance both the quality and quantity of colostrum – a key factor in porcine survival and production.

Figure 2. A normal sow comfortable with feeding her newborn piglets.

In this article, three ideas are introduced, which, in combination, can help improve the quality and quantity of colostrum. The quantity of colostrum is enhanced by correct feeding routines in gestation. The use of a simple caliper to monitor sow condition is introduced.

Needleless technologies are revolutionising vaccination protocols. In combination with a “rope trick”, which can transfer nursery respiratory pathogens to gilts pre-breeding, the quality of the colostrum can be enhanced. Colostrum is key to pig survival and production.

Pigs, in association with their diffuse epitheliochorial placenta, are born basically naive. Health management programmes need to be taught to the farm staff to correctly protect, then expose, this naive piglet to the world and facilitate its transformation into a healthy, active finishing pig. The initial key is providing colostrum of adequate quality and quantity.

Gestation feeding for sows can be divided into periods (Table 1).

Feeding regimes for the gestating sow influence colostrum availability to the neonate, so it is vital to get the feeding levels correct. A common mistake is to have the sows too fat during pregnancy.

The more a sow eats in gestation, the fatter she will get. A fat sow may then produce too much milk/colostrum pre-farrowing, resulting in pain and discomfort.

This pain and discomfort results in udder oedema – often misdiagnosed as mastitis – and the sow becomes reluctant to allow the neonates to suckle. This phenomenon is breed-specific, being more common in large white/Yorkshire and less in Duroc-crossed dams. Affected sows lie on their abdomen, rather than adopting a nursing position (Figures 1 and 2).

Negative correlation is seen between gestation feed intake and lactational intake. By correctly feeding the gestating sow, it will be encouraged to eat more in lactation.

Lactational feed intake drives milk production, which increases piglet weaning weight and reduces sow weight loss; the weaning to service interval will shorten as a result, which correlates with enhanced subsequent farrowing rate and total litter size. Lactational feed intake is a key parameter on pig farms.

The traditional technique to determine whether the feed intake in gestation is adequate is to estimate body condition score, by eye, using a 1 to 5 scoring system (1 is thin and 5 is fat). However, this assessment is notoriously inconsistent, with different “scores and opinions” given by different advisors and staff. In fact, trends – rather than absolute scores – are important.

Backfat ultrasound measurements are more definitive and can be extremely useful, but the technique requires training and positioning of the measurement must be consistent. With loose housing of sows, this can be a very difficult measurement to accurately obtain.

A novel tool has been introduced by North Carolina State University. A simple caliper, placed at the level of the last rib (Figure 3), has been shown to provide consistent results between a number of different operators (Figure 4).

Using cameras, an individual report can be generated for each sow (Figure 5) and collated into a database (Figure 6). The sows can then be marked so the whole gestation team knows to lower (Figure 7) or raise (Figure 8) feed availability.

It is recommended sows are assessed at weaning and at 30, 60 and 90 days of pregnancy. Each can then be individually assessed and suitable changes made.

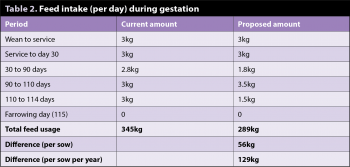

Not only can positive benefits be seen from enhancing colostrum availability and lactational output, but potential cost savings are possible through reduction of feed intake in gestation (Table 2).

After more than 15 years of developing intradermal and subdermal injection technologies, needleless vaccination protocols are becoming normal practice on UK farms.

Previously, this technique was only available for vaccines not commonly used in mainland UK. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSv) and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae intradermal vaccines – together with many others in development and effective combinations of these vaccines in a single shot – have, at last, opened the door for major changes in vaccination protocols in the pig industry (Figures 9 and 10).

The major advantages of the needleless vaccination system are a reduction in injection stress on the pig (Figure 11), because injections can be administered intradermally anywhere on the body.

Handling of the pig is much easier, and needleless vaccination facilitates injecting areas of the pig that should not be targeted by needles because of the risk of infection – for example, the valuable pig ham. With needleless vaccination protocols, damage to the carcase is minimal, if nonexistent (Figures 12 to 14).

Once more vaccines are available for gestating sows – for example, parvovirus, erysipelas and Escherichia coli – we can move towards a goal of eliminating needles for immunisation protocols, at least.

The sow’s innate immunity is transferred to the neonate piglet within the first six hours of life, but this wanes over time to a stage where it can no longer protect the piglet.

By the time the piglet is 28 days old, protection against most common pathogens has effectively vanished from the sow’s colostrum. Challenge by endemic pathogens on the farm should trigger a piglet’s own active immunity. This is normal, but the pathogen load the weaned pigs are exposed to must be low enough to induce an effective immune response without causing the pigs to become clinically sick.

The major issue is often ensuring adequate immunisation of gilts against the major nursery and finishing respiratory pathogens on the farm. Use of vaccines has assisted this process, but they have a major drawback. Many of these pathogens are RNA viruses that are unstable and mutate.

Additionally, the vaccines are commercially produced and are, thus, not farm-specific. It is possible to make more farm autogenous vaccines, but this can be costly, and it takes a long time to produce the product and undertake the appropriate safety tests.

Using a cheap, unbleached rope, the pathogens and organisms living in the nasopharynx of the nursery pig can be moved from the nursery, where the pathogens load is high, to the gilt-rearing area on the same farm.

Place short ropes in the nursery for a couple of days, allowing the pigs to play with the ropes (Figure 15).

Once the ropes have been chewed and are wet with saliva, move them to the gilt house and place them in the relevant pens (Figure 16). Gilts will usually chew and destroy the ropes.

Transfer of organisms between the nursery pig and the gilt will cause her to mount an immune response to these organisms, which should facilitate passive protection to her own offspring via colostrum.

Using this technique may help with respect to:

Techniques to provide immune stabilisation are not intended to replace vaccination protocols, but should be used alongside them to boost the effectiveness of commercial vaccines.

This article illustrates three technologies that can be used by veterinary surgeons to enhance the health of the pigs under their care through the provision of high-quality colostrum.