21 Oct 2019

Tony Andrews covers the variety of problems, including toxicity, that may occur when feeding this plant to cattle.

Sweet potatoes have become a food increasingly eaten in the UK, both at home and when eating out. At times, they are offered as animal feed because of oversupply or from downgrading. Despite the name, these plants are not potatoes, but members of the Convolvulaceae family. In the UK, they have mainly been used as vegetable waste for feeding finishing beef cattle. They have been used as a replacement for potatoes, although their nutritional profile is usually slightly different.

Sweet potatoes should only be fed following the receipt of expert advice and introduced to the ration slowly. Problems can occur following feeding. The most serious is toxicity following damage of the tubers, usually with subsequent fungal growth, and involving signs similar to those of fog fever. No specific treatment exists, although NSAIDs may assist.

Sweet potatoes have been cultivated for at least 5,000 years, but in Britain they have only been consumed in any numbers for less than 50 years.

The vegetable probably originated in the tropical regions of Central or South America (Figure 1), and can be grown in any area with a warm climate and sufficient water. They were introduced to – or arrived naturally in – Asia, Africa and Pacific areas as a reliable and staple food source that could survive typhoon conditions.

Originally, in Britain, the vegetable’s main consumption was in ethnic communities, but it has now become more widely used in other diets and appears on many restaurant menus. In recent years, consumption in the US has markedly fallen and it is suggested this is possibly because sweet potatoes are considered a food of the poor.

Sweet potatoes (Figure 2) are not actually potatoes and are not even in the same plant family (Solanaceae). The plant is Ipomea batatas, which is in the Convolvulaceae (the bindweed or morning glory) family (Figures 3 and 4). The part of the vegetable eaten in Britain is the root tuber, although in some countries the shoots and young leaves are also consumed. The tubers can be of various colours (Figure 5) and tend to have a hard surface. Dependent on type, their flesh is either a bright orange or pale creamy colour.

In Britain, sweet potatoes have become a relatively popular human food and, when in surplus, have been used as a byproduct for feeding farm animals. Those eaten by animals in Britain are imported and are either in excess of retailers’ requirements or have been downgraded. The dry matter (DM) content of fresh sweet potatoes can be the same as potatoes (20%; Parish, 2017), although when imported as a feed source, sweet potatoes can be dried to about 87% DM feed source. Therefore, the DM analyses given by Thibodeau et al (2002) were:

Sweet potatoes’ nutritional value (Table 1) does vary and this appears to be the result of different varieties or following their processing in varying forms for human consumption. If they are to be included as a major component for animal feed then a feed analysis is advisable, as well as advice from an advisor (nutritionist, veterinarian and so on) with experience in their use.

They are an attractive feed, just as with potatoes, because of their high energy level and good palatability. They can be included in ruminant, pig and poultry diets, although their use in cattle will be concentrated on in this article.

In pigs, maximum recommended inclusion levels in the US range from 5% in weaner and grower diets, to 12.5% in finisher and 15% in sow diets. In poultry, recommended inclusion rates again vary from 5% in broiler diets, to 10% in breeder diets and 15% in layer diets. The maximum inclusion level in beef diets in the US is recommended to be about 20% (Table 2), although lower levels have been suggested in the UK.

In other parts of the world, sweet potatoes are used in sheep diets and dairy cow rations – both up to 20% inclusion rate – but without more recorded practical experience of their use in the UK, their use is probably not advisable.

Use of potatoes is easier to recommend than sweet potatoes, as farmers in those parts of Britain where they are grown or are processed can usually rely on a relative continuity of supply for long periods – especially in the winter months – or all year round.

This is unlikely to happen with sweet potatoes because they are imported and will usually only be available when quality or oversupply problems occur. It is, therefore, likely that supplies will tend to fluctuate and be unreliable.

If sweet potatoes are too rapidly introduced to a ruminant diet then acidosis is a potential consequence. Even when using them as a straight substitute for potatoes, this can occur because the DM content and energy levels can tend to be higher.

Therefore, they should always be introduced slowly to the ration – ideally by initially mixing with the previous diet – and adequate roughage levels should always be available.

It is possible that if the sweet potatoes are not chopped up, they can result in smaller ones being swallowed without suitable chewing, and potential oesophageal obstruction and consequent bloat.

Dental problems have been reported in North America because of the acidic nature of the vegetable. Defects follow long-term feeding, but provided the feed is just used for fattening cattle, it should not be of any consequence.

As sweet potatoes are a high-energy feed, their rapid introduction to a diet can result in laminitis. This is the same as with any other high-carbohydrate diet and, again, as with acidosis, roughage should always be available and the sweet potatoes introduced slowly.

When the plant is pruned in North America, dogs may scavenge the plant bits of vine. This usually results in the normal signs expected of eating something unsuitable, such as drooling saliva or foaming at the mouth, or vomiting and diarrhoea. Other signs can develop as the plant toxins can affect the heart, kidney, liver and lungs.

Again, in North America poisoning follows eating parts of the vine and the signs are similar to those in dogs.

It is quite possible to feed sweet potatoes to beef cattle without problems. If the sweet potatoes are of good quality, introduced slowly to the diet and used at the recommended levels then they can provide a good source of nutrition in cattle.

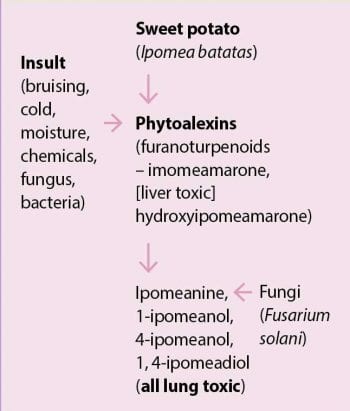

As they are not a common animal feed, knowledge of the problems associated with sweet potatoes may not be known by all vets and probably most farmers. If they are damaged or bruised, they can become very toxic.

The toxicity problem was first reported in the 1920s, in Japan and the US. Several such reports of poisoning from the US exist. Their introduction as a feed source in Britain has resulted in such reports also occurring here – the first in England and Wales was recorded in October 2007 (Veterinary Record, 2007; Mawhinney et al, 2008; Meikle, 2008).

In the incident involving a herd of 15 Limousin cross beef cattle (one bull, seven cows and seven calves), six cows died over a four-day period after consuming 7kg of sweet potatoes daily for more than a week. While outbreaks of poisoning only occur occasionally, they can result in large numbers of deaths, such as when 200 cattle died in Wisconsin in 2011.

The onset of signs will depend on many factors, including the type and quantity of toxins present, the quantities of affected sweet potatoes fed, other feeds provided, previous starvation or other stresses. Illness can occur within 24 hours of feeding damaged sweet potatoes, but may be delayed for several days.

Usually a sudden onset of acute respiratory disease will occur, but without any alimentary signs. Tachypnoea, dyspnoea with severe distress often with mouth breathing and salivation occurs. Affected animals are often reluctant to move. Therefore, in essence, signs of toxicity are usually those of acute respiratory distress and can result in rapid deaths. At times these may appear as sudden deaths (Figure 6).

The main differential diagnoses are other causes of acute cattle respiratory disease. These will vary according to the age of the animals. In growing and adult animals, they tend to be less common than in younger cattle and weaned calves. The main differential diagnoses in older animals are given in Panel 1.

Provided it is realised that sweet potatoes can cause acute respiratory signs then usually diagnosis is relatively straightforward. Therefore, a history of feeding sweet potatoes exists with signs only present in those animals receiving the feed. When the vegetables are examined, it would usually be the case that some will be seen to be damaged, with fungus present. However, the fungus may not be very obvious and rarely, it may not be present.

Postmortem examination shows the lungs are heavy, do not properly collapse, and have areas of firmness with oedema and emphysema. Severe interstitial pneumonia and absence of other causes of respiratory disease with lack of a tracheitis exist. Histology shows the main cells affected are alveolar type II pneumocytes and non-ciliated epithelial cells mainly lining the bronchioles. In Britain, it may not be possible to have the feed examined for ipomeanol toxins.

The main differential diagnosis is fog fever, known in the US as acute bovine pulmonary emphysema and oedema (Campbell, 2012), and usually this can be eliminated by the history. However, the pathological findings are similar. Potential differential diagnoses are shown in Panel 1.

No real proven specific treatment exists, although NSAIDs may assist. The sweet potato feed should be immediately withdrawn and, initially, an all-roughage diet introduced until cases are resolved. As little can be done to treat, casualty slaughter has been used, but if the animals are transported then they will be stressed and may die.

Therefore, if they are taken to an abattoir, arrangements should be made for their immediate slaughter. However, the author has been given anecdotal advice that some evidence might exist that the toxin might be present in the carcase, although he has been unable to confirm this and it has not been his experience.

In those animals not showing signs in an outbreak, they are likely to continue without any signs. Those with signs that do recover then often remain well. However, during the repair process extensive epithelial hyperplasia of the alveoli and bronchioles occurs; this was originally called pulmonary adenomatosis (Doster et al, 1978).

In addition, debate still exists as to whether, besides the direct toxic effects on the lungs, the toxins can make the lungs more susceptible to other diseases. Therefore, furanoterpenoids can suppress pulmonary immune functions and it has been shown to enhance the replication of parainfluenza virus in cattle lungs (Li and Castleman, 1991).

Sweet potatoes have been successfully fed to cattle in many parts of the world where they are grown. They have also been used without any problems on some British farms as an adjunct mainly to the diets of finishing beef cattle.

If sweet potatoes are considered as being a potential feed source, they should only be used by very experienced stockpersons. Feeding advice should be obtained from those experienced with using them. The animals will need to be seen at different times throughout the day, and not just once or twice daily when being fed.

Introduction to sweet potatoes should be gradual and initially, should be less than 5% of the DM of the ration. This can be stepped up in stages about every five days, provided no indications of problems occur.

Every new batch of sweet potatoes must be thoroughly checked on arrival, and if any signs of damage, moisture or a suggestion of any fungal growth (Figure 7) occur then they should not be fed. If when feeding the batch similar changes are seen then, again, feeding should cease immediately. In fact, if any doubt exists about a sweet potato batch, do no feed it.

The author has, over the years, received much assistance in this topic from Ian Mawhinney and Jo Payne, as well as several vets and farmers.