16 Apr 2018

An update on three main causes of foot disease in sheep, looking at its diagnosis, control and treatment.

This article gives an overview of the main causes of lameness in sheep by focusing on the three most common diseases present in the UK – all of which are infectious in nature: interdigital dermatitis, foot rot and contagious ovine digital dermatitis. The most recent and relevant findings regarding the aetiological agents are discussed. Also, a fresh look at the options available for diagnosis and control – specifically the role of the vet – in dealing with lameness at a flock level, is presented. Finally, a summary of the choices available for treatment is provided.

Sheep lameness is rightly recognised as one of the major health, welfare and production-limiting conditions.

The main causes of sheep lameness in the UK are infectious diseases. Interdigital dermatitis (ID) and foot rot have been on “the podium“ for some time, although contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) seems to have become more prevalent1.

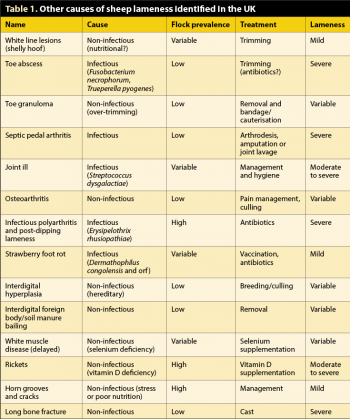

These three conditions account for more than 90% of cases of lameness in the UK2 and are almost always described at a flock level. Other causes of lameness commonly encountered in clinical practice – but either have much lower prevalence or account for individual problems – are white line disease (shelly hoof), toe abscess and toe granuloma. Table 1 gives an overview of the other causes of sheep lameness identified in the UK.

The dogma we have become familiar with through lectures and textbooks is ID is caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum, and benign foot rot, although clinically indistinguishable from ID, is caused by Dichelobacter nodosus, with virulent strains causing a more severe clinical presentation, with under-running of the sole and exposure of sensitive tissue.

More recent evidence, though, seems to suggest ID and foot rot are two stages of the same disease. The causative agent, in both cases, is D nodosus, with F necrophorum acting as opportunistic pathogen3.

What is important to remember about D nodosus is, without the right conditions – such as a wet and warm environment, high stocking rate and initial damage to the interdigital skin – it is not able to cause disease.

Furthermore, the bacteria can only live on ruminant feet, and can survive in the environment for up to 14 days. This has important implications for control of the disease, as without introducing sheep carrying the bacteria, no foot rot/ID should be in the flock. Additionally, it is important to remember not all strains present the same virulence and, therefore, the same severity in clinical signs.

With CODD, the general consensus seems to be Treponema species is the causative agent of the disease. Again, D nodosus has also been isolated from cases of CODD4, as well as Treponema been isolated in cases of foot rot3, which suggests what we describe as foot rot might actually be a multifactorial disease with multiple microorganisms involved having a synergistic role and, possibly, different clinical presentations.

Regardless of the causative agent, one of the main challenges is the prompt and effective recognition of lame sheep, to allow for immediate treatment of as many cases as possible, as well as being able to identify those that reoccur after treatment.

Although foot rot is considerably the biggest problem, it is also the most common lesion incorrectly named by farmers – as shown in a survey where many farmers would tend to name any hoof horn lesion as foot rot – with white line disease being the most misdiagnosed condition2. This suggests veterinary involvement should seek to confirm diagnosis, and, obviously, implement a treatment and control plan. The clinical aspect will usually be sufficient for a diagnosis (Figures 1 to 3), but, for definitive confirmation, the best option is to submit a swab from the lesion for PCR or bacterial culture.

Another fundamental point is knowing the extent of the problem. Before embarking in any control programme, it is necessary to have a clear idea of the prevalence of lameness. The number of sheep affected, age group, speed of onset and degree of lameness are all important questions that need to be addressed. The prevalence of lameness seems to have dropped from 10% to 5% in the past few years1, which is in line with the 2011 Farm Animal Welfare Council opinion and probably a good indicator of an achievable target for commercial flocks.

Once a clinical diagnosis is reached and the extent of the problem is clear, some practical questions should be considered:

The scientific evidence suggests catching mildly lame sheep within three days of first becoming lame is associated with a decreased prevalence of lameness1. It also suggests targeted individual treatment is considerably better than flock treatment using a foot bath7. From this, it would be recommended to regularly (for example, once to twice a week) inspect sheep for lameness, at each observation catch every sheep showing even a mild degree of lameness (scored one and above) and individually treat them.

While this might be the gold standard of a lameness control programme, it might not work for all farmers. The key, as always, is to work with them in setting achievable goals, and propose solutions that are practical and fit within their existing system.

Other options that should be considered are included in the “Five Point Plan”8. One is the always fundamental quarantine of all incoming stock (including both purchased and returning stock) and which should be applied anyway as a baseline biosecurity measure in every flock. A licensed vaccine for foot rot is also available, with the recommendation to vaccinate all stock implemented at a critical time of the year (for example, housing).

Culling repeat and worst offenders, as well as breeding from more resistant animals, is another option to reduce incidence of lameness in the flock.

Regarding foot bathing; if best practice is followed, it can definitely play a role in the control of lameness7. Handling facilities (race and penning) have to be excellent. All sheep should remain in the bath for the recommended length of time (depending on the chemicals used and the addition of a surfactant), and all sheep are required to stand on a clean, dry and possibly hard area for at least half an hour after foot bathing. If all these measures are not in place, this practice can make the problem worse by increasing spread of the disease.

The frequency of foot bathing is another point to consider, with suggestions of a weekly frequency being a solution for elimination/treatment of the disease9 and regular (a few times a year, at housing and gathering) for prevention.

Finally, chemicals that can be used are either formalin or zinc sulphate.

Strong evidence suggests early treatment of individual sheep affected by foot rot with parenteral antibiotics is the best and possibly most cost-effective option10. The active principles that have shown efficacy are oxytetracycline (20mg/kg), gamithromycin (6mg/kg), tilmicosin (10mg/kg) and florfenicol. Topical antibiotic sprays containing oxytetracycline are also an option for mild cases and to reduce further environmental contamination.

At the same time, an absolute ban on trimming feet as a treatment option for foot rot11 is well established, with a very positive farmer uptake on this message1. Although research has focused mainly on foot rot, it is reasonable to assume similar advice would be applicable for CODD.

Avoidance of trimming affected feet to limit the spread of the disease and to aim instead for targeted parenteral antibiotics is likely the best option. Cases of CODD do not seem to respond to either formalin or zinc sulphate foot bathing, while long-acting amoxicillin (15mg/kg), oxytetracycline (20mg/kg) and tilmicosin (10mg/kg) have all shown efficacy.

As for any other disease to tackle, you first need to know your enemy. Veterinary involvement is crucial in dealing with lameness – both for definitive diagnosis, as well as tailored advice. As usual, the need for a health plan with clear guidelines of first-line treatment and control measures (from biosecurity for infectious diseases to specific lameness control) is a must. It also needs to be acknowledged we are working with our clients, and whatever advice will be given has to fit with an existing system and busy schedule.

Data collection (diagnosis, prevalence of lameness and lameness scoring), a clear idea of the resources (routine treatments, handling facilities and available labour), and a set of sensible and achievable goals are the basis for a successful collaboration, and for the control of this significant production-limiting condition.