23 Sept 2021

In this article, Charlotte Mouland explores common infectious and non-infectious conditions causing lameness in sheep, and discusses latest treatment and control strategies.

Close examination of all four feet is essential to diagnose the cause of lameness. Image: © David Daniel / Adobe Stock

Despite farmers identifying lameness as the biggest welfare concern facing sheep in the UK1, prevalence still sits above industry targets. In 2011, the Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) set out recommendations to reduce the prevalence of lameness in the UK flock to 2% or less within 10 years2.

While great improvements have been made, with global mean period prevalence of lameness falling from 10.2% in 20043 to 4.9% in 20134, the most recent estimate of farmer-reported sheep lameness suggests the industry is unlikely to hit the FAWC target, reporting an average prevalence of 3.2%5.

As well as its welfare implications, lameness has been identified as a hotspot for antibiotic use in the sheep sector6, with an estimated 75% of prescribed antimicrobials being used to treat lameness7. Tackling lameness was a specific industry target set out in the Targets Task Force Report 20176. While it is entirely appropriate to treat infectious causes of lameness with antibiotics, the focus of lameness control needs to shift to a holistic approach, and the report called for increased uptake of the Five-Point Plan8, which we will discuss later.

In this article, the author will explore the common infectious and non-infectious conditions causing lameness in sheep, and the recognised treatments and control strategies in 2021.

Footrot is the leading cause of infectious lameness in the UK, accounting for around 70% of cases4.

Our understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of footrot has changed in the past few years, and it is now thought that Dichelobacter nodosus is the invading agent and that Fusobacterium necrophorum acts as a secondary pathogen9. Initial maceration of the interdigital skin caused by prolonged exposure to moisture, rough ground or rough herbage allows D nodosus to invade and colonise10.

The clinical signs of footrot can vary from interdigital dermatitis, or scald – which presents as reddening or blanching of the interdigital skin with a grey discharge – to complete separation of the sole and abaxial hoof wall. D nodosus releases proteases and elastases that create a build-up of necrotic material, resulting in the distinctive odour associated with footrot infection11. The severity of clinical signs depends on the presence or absence of the acidic protease AprV2, environmental conditions and host susceptibility12,13.

Diagnosis of footrot is based on identification of lame sheep and clinical examination of all four feet to look for characteristic changes. This can be done with reasonable accuracy by trained farm staff14,15.

Contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) was first identified as a novel disease of sheep in the UK in 199716. A survey of sheep farmers in Wales found that 35% of respondents reported the presence of CODD on their farms17, while a similar survey in England indicated a 58% on-farm prevalence18.

The aetiopathogenesis of CODD is not yet fully understood, but so far we know that it is caused by Treponema species, similar to those involved with bovine digital dermatitis. Furthermore, evidence is growing to support a positive correlation between D nodosus and CODD, and a big risk factor for developing CODD is the presence of footrot19.

CODD lesions begin at the dorsal coronary band, causing ulceration or erosion, with or without alopecia. This progresses to under-running of the abaxial hoof horn and potential avulsion of the hoof capsule20. CODD is considered a very painful condition and studies suggest that sheep with CODD become more lame than sheep with footrot or interdigital dermatitis20,21. Diagnosis of CODD is made on clinical signs, but it is often confused for other foot conditions and severe cases can be very difficult to distinguish from other diseases.

Additional to the common infectious causes of lameness are non-infectious conditions, which are generally considered less prevalent. These include shelly hoof, toe granulomas and toe abscesses.

Shelly hoof is caused by a degeneration of the white line along the abaxial wall, causing separation of the hoof wall, creating a pocket where mud and other debris can accumulate. The cause of shelly hoof is not well understood, and may involve some association with nutrition and/or genetic predispositions22.

Toe granulomas are protrusions of granulation tissue, most commonly as a result of over-trimming and damage to the underlying corium.

Toe abscesses are a consequence of white line disease, where separation or a puncture wound of the white line leads to the formation of an abscess22.

Traditionally, the recognised treatment for footrot was trimming back affected horn to “let the air in” and combat D nodosus because of its anaerobic nature.

However, a trial23 found that foot trimming without administering parenteral antibiotics doubled the recovery time from footrot, compared with parenteral antibiotic treatment alone. In fact, sheep only treated with topical spray recovered quicker than individuals that were treated by trimming and topical spray, suggesting a detrimental effect of trimming, likely due to the damage it causes to the underlying corium23.

Furthermore, routine foot trimming of sheep is considered an unnecessary practice, as the rate of wear of the sole horn will naturally vary throughout the year24. Concern exists that routine trimming can alter the shape of the foot, making it more prone to infection, and that the unnecessary stress and close handling of the sheep may increase the spread of footrot and CODD.

The current recommended treatment for interdigital dermatitis is topical antibiotic treatment for all four feet, or effective footbathing if large numbers of lambs are affected8,25. For treatment of footrot (when the horny tissue is also involved), parenteral long-acting oxytetracycline or long-acting amoxicillin is indicated, as well as topical antibiotic treatment of all four feet25.

No treatments are currently licensed for CODD, and a limited number of randomised control trials have been performed to date. One study demonstrated a 71% clinical cure rate in sheep treated with a single dose of amoxicillin19 and studies have also shown good efficacy, both in vivo and in vitro, for treating individual cases with tilmicosin and tulathromycin26.

However, it should be noted that no treatment yet has been shown to achieve a bacteriological cure and repeat treatments may be required. When prescribing antimicrobials for lameness, we must ensure we are working in line with the current BVA guidance on responsible use of antibiotics.

For cases of shelly hoof and toe abscesses, careful paring away of loose horn to remove debris and establish drainage may be all that is required. Remember that foot trimming equipment can act as a very effective vector for infectious causes of lameness, and careful disinfection and handwashing (or changing gloves) between handling lame sheep is a must. The survival of Treponema species on gloves has been demonstrated for a minimum of five days27.

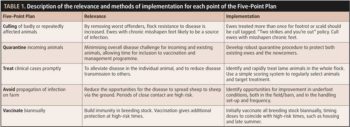

In response to the FAWC’s report in 20112, the Food Animal Initiative (FAI) developed and released the “Five-Point Plan for tackling lameness in sheep” (5PP)8,28. The document incorporates the latest published science, as well as practical experience from sheep farmers who have achieved low levels of lameness on their farms.

The plan was trialled on a flock of 1,000 outdoor lambing ewes, where a reduction in mean prevalence from 7.4 (plus or minus 4.9%) to 2.6 (plus or minus 2.9%) was demonstrated across four years. The five points of the plan are summarised in Table 1.

Uptake of the 5PP has been limited, with a study reporting only 5.8% of sheep farmers adopting all five points5. When investigating the barriers to uptake, common themes included limited on-farm infrastructure and facilities, time and financial restraints, and a perception that lameness is practically more difficult to control than other diseases29.

Furthermore, veterinarians were not often sought for proactive lameness advice and respondents felt a lack of specialist sheep vets were available, limiting the development of congruous farmer-vet relationships29,30.

Although prevalence of sheep lameness is moving in the right direction, advancements still need to be made to meet industry targets, improve productivity and, most importantly, enhance animal welfare.

It has been previously demonstrated that sheep farmers want their vets to get more involved with their sheep flocks30, so why not strike up a conversation about sheep lameness next time you are on farm?