22 Jan 2018

David Harwood summarises proceedings from the Goat Veterinary Society autumn meeting held in Taunton, Somerset.

Figure 2. An outstretched stance in a urolithiasis case. Image: Alex McSloy / RVC.

The Goat Veterinary Society’s autumn meeting was held at Taunton Racecourse, and attended by 58 members and speakers, with a good mix of vets and goat owners/stock keepers. Programme secretary Kathy Anzuino had developed a varied programme for delegates.

Kicking off was a recorded presentation from New Zealand by Laura Deeming, who is working on a PhD thesis considering the causes of lameness, the importance of its early recognition, and its impact on welfare and productivity. The dairy goat sector is focused mainly in the Waikato region of North Island, in which 45,000 goats are kept on 72 farms (part of a “dairy goat cooperative” and responsible for 90% of the total national production).

Lameness has an impact on social behaviour and interaction, lying and feeding behaviour, and overall productivity. Ms Deeming emphasised the importance of its early recognition, saying “it is easy to recognise a goat walking on three legs (Figure 1)”, but recognising subtle changes in locomotion that precede visible lameness should be the aim.

Lameness is almost always underestimated by herd owners/stockmen, and the perception of what is/is not lame will often depend on the severity of the herd lameness problem. Unlike cattle, goats tend to run rather than walk, and this may mask a painful limb or foot that may be more easily recognised at a slow walk.

In addition to the recognised classifications of “normal gait” and “mild, moderate and severe lameness”, Ms Deeming suggested adding an “uneven gait” category, in which a mild variation from the normal gait exists. The gait may be slightly uneven, including shorter strides, or an inward or outward swinging of the hoof at each stride may be present. By regular observation, these early gait change cases can be recognised and remedial action taken before true lameness develops.

James Adams, a staff clinician in large animal internal medicine at the RVC, described the main risk factors of caprine urolithiasis, including diet, damage to the bladder wall in which mucoprotein sediment can develop, bladder infection, hydration status (specifically access to water – for example, if a trough is frozen) and lack of urination. Access to water and reduction in urination frequency can be recognised in subordinate goats, or when dominant animals are in the group.

The main stones formed are struvite, calcium carbonate or calcium phosphate – each linked predominantly to diet. The male urinary system results in potential blockage sites due, in part, to a narrow urethra (compared to females), with specific anatomical blockage sites at the sigmoid flexure and urethral process. Clinical signs include obvious failure to urinate, an “outstretched” posture (Figure 2), vocalising and restlessness.

Blood sampling will show an increased blood urea, creatinine and potassium, and decreased sodium chloride and phosphorus. Radiography and ultrasound are both useful ancillary aids. Conservative treatment is not feasible if a stone is clearly present.

Surgical considerations include tube cystostomy, perineal urethrostomy and marsupialisation. Between 2009-17, 38 goats were admitted to the RVC with known outcomes, of which 21 were discharged after successful treatment. Mr Adams emphasised the importance of rapid intervention – those euthanised either pre or post-surgery were mainly the result of irreparable urethral damage.

Nicola Bates of the Veterinary Poisons Information Service (VPIS) shared the service’s experience of goat poisoning. She stated the VPIS database held records of 272 suspect and proven poisoning incidents involving around 320 goats – many of which appeared only to be a record that a toxic product was thought to have been consumed. By far the largest group were poisonings involving plants (58%), followed by agrochemicals – predominantly rodenticides (32%). Most of the goats that had reportedly consumed a rodenticide (amounts unknown) remained fit and well.

Plant poisoning is a recognised problem due to goats’ browsing and inquisitive behaviour. Cases mainly involved consumption of hedge clippings, often thrown into their paddocks in urban areas, while lack of toxicity awareness also resulted in owners inadvertently feeding toxic plant material. Rhododendron toxicity was the most commonly reported, followed by Pieris (Figure 3). Both contain a grayanotoxin, toxicity signs of which include hypersalivation and rumen content regurgitation, with potential for aspiration pneumonia.

Generic treatments in all suspected poisoning cases include gut decontamination – either dosing with activated charcoal or, in severe cases, undertaking a rumenotomy to remove the material. Supportive care includes rehydration therapy, pain relief and managing complications such as aspiration.

Margit Groenevelt, a practitioner from the Netherlands, stated a different approach is required when treating pet as opposed to commercial goats. All goats, no matter how they are kept, are classified as farm animals; however, they are all susceptible to the same conditions, but the money pet owners may be prepared to spend on treatment may be vastly different.

Their aspirations in the face of a problem, such as Johne’s disease or caprine arthritis encephalitis, will also differ, with control by culling often being an unpalatable option.

Nutritional conditions – particularly obesity – can be a common problem due to inappropriate diets and too many titbits. Parasite control is often exacerbated by small overgrazed and contaminated paddocks. Problems related to “old age”, such as dental issues and OA, are further complications and can be challenging.

Matt Pugh, a director at Belmont Farm and Equine, described an initiative to control known Johne’s disease problems in herds supplying milk to a local cheese manufacturer, posing the question: “Eradicate or control?” Control of clinical disease in many of these herds has been achieved by a vaccine that has a marketing authorisation for use in goats in the UK. Lack of clear guidelines as to the duration of the resulting humoral antibody (and, hence, its potential effect on the ELISA diagnostic test) has been problematic.

Work in the Netherlands has suggested the antibody will have waned by around two years of age. Mr Pugh was of the view the antibody detected in vaccinated goats after this would suggest they had been exposed to repetitive environmental challenge with Johne’s disease organisms. Serological screening was supplemented by pooled faecal PCR testing, with the recognition false-negative results may be more common than in cattle. A screening exercise of 545 goats on 11 farms resulted in an overall seroprevalence of 61%, although on one farm, 100% of goats tested were positive, while on another, the figure was zero. Any advice given must be farm specific.

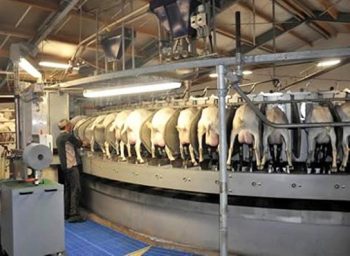

Ian Ohnstad of The Dairy Group stated, regarding goat milking process, the main objectives were to milk quickly, completely and safely, with minimum adverse effects on teats and teat ends. This, in turn, relies on a correct milking routine using correctly operating equipment by application of the correct ergonomics. The milking routine should ensure teat cleanliness, stimulation and letdown, thus ensuring milk quality and reducing mastitis risk.

A useful explanation was given of the differences between dairy cows and goats with reference to milk letdown. In cows, only around 30% is present in the teat cistern and 70% in the alveoli, while in goats, almost 80% is cisternal and around 20% alveolar. As a result, the goat milking process is much more rapid. Thinking on operating levels for goat milking equipment (Figure 4) is:

Due to the number of goats being milked on some larger farms, and a unit attachment rate of three to four seconds per goat, it is important to get the ergonomics right for the milking personnel; repetitive strain and back injuries can be problematic.

Caroline Rank of Belmont Farm and Equine gave an update on a project her practice has been involved with that aims to establish achievable, acceptable targets for kid rearing pre-weaning (Figure 5). The work has been undertaken on nine commercial dairy goat farms, developing and measuring key performance indicators. Measurements included birth weight, weight at disbudding coupled with an assessment of colostral intake, weight at weaning and a health recording protocol.

Of 327 bloods from all farms analysed for colostral intake, 83% were adequate and 17% inadequate, but from farm to farm, the variation was 17% to 100% adequate intake. It is recognised in calves adequate colostral intake has a positive influence on future health.

A total of 612 kids were tracked for health-related problems and 26.5% were treated for pneumonia (farm range 1% to 66%. In the same cohort, 24.2% developed diarrhoea, though causes were not established. Mortality rate pre-weaning was 9% (farm range 5% to 17%), which is significantly higher than expected and figures are under further analysis.

Miss Groenevelt’s second paper was on use and restrictions of antibiotics in the Netherlands. In 2007, the country was one of the highest users of veterinary antibiotics in mg/kg in Europe, with action deemed necessary.

A taskforce was set up that included manufacturers, wholesalers, vets and their clients. It was initially targeted at the veal, cattle, poultry and pig sectors with an aim of achieving a 20% reduction overall by 2011, and 50% by 2013. This was achieved by stopping strategic or preventive blanket therapies, reducing whole herd treatments, stopping “routine” dry cow therapy and restricting certain antibiotics completely by a combination of self-regulation, CPD and government legislation.

As an example, farms must have a yearly updated health plan and yearly farm-specific treatment plan with a “first choice antibiotic” (from a specified list); “second choice antibiotics” were only possible for mastitis tubes and under exceptional circumstances. The “third choice list” includes fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins and colistin, with strict restrictions on their use.

Goats are not yet subject to these regulations, but the sector in the Netherlands is starting a similar, but voluntary, monitoring scheme. The only licensed antibiotic is oxytetracycline.