18 Sept 2020

John Carr BVSc, PhD, DPM, DipECPHM, MRCVS and Mark Howells MA, VetMB, DBR(Dist), MRCVS discuss opportunities available to vets to have a positive impact on the health and profitability of their clients’ herds.

Today’s veterinary surgeon needs to be able to offer 360° advice on pigs.

This article looks at four exciting opportunities where veterinarians can impact their clients’ pig farms to improve health and profitability.

Feed is the major cost in animal production systems. In pig production it accounts for between 60% and 70% of the cost of production (COP) – this eclipses the 4% to 6% of COP spent on health, including veterinary products.

Any change in the amount of required feed provides instant rewards to the bottom line.

Two exciting possibilities exist for reducing feed costs.

The energy contained within feed is described as gross energy (GE), but the energy available to the pig is defined as net energy (NE).

This is a difficult number to evaluate, as all the feed ingredients must have a recognised NE value. Only over the past decade have these values become well established.

The adoption of the NE system would provide a substantial saving to the pig industry in both carbon footprint and economic value (Figure 1).

Danish pig producers have adopted their own independent energy system called potential physiological energy (PPE), which is based on experimental evidence relating to energy utilisation by pigs of specific ingredients. This helps them to gain a major cost advantage over their global competitors.

The results of PPE and NE are generally close enough that if the UK herd was to adopt the NE system,the gap in efficiency with Denmark would close.

Genetic improvement has been extremely successful in improving the efficiency of pig production. The pig industry now targets production of 12 pigs weaned per batch farrowing place, compared with 10 pigs weaned per batch in the 1990s.

When comparing the advantages and disadvantages of this 20% increase in output, it is important to consider feeding these extra pigs. The selection of boars with improved food conversion ratio (FCR) reduces the amount of feed required to produce the saleable product.

If the FCR required to produce a 100kg live weight pig is 1:1.27, this means 127kg of feed is required to produce a 100kg pig; reducing the FCR by 0.1 to 1:1.26 would save 10kg of feed, reducing the carbon footprint.

With today’s pigs often finishing at 115kg live weight, the impact is even greater.

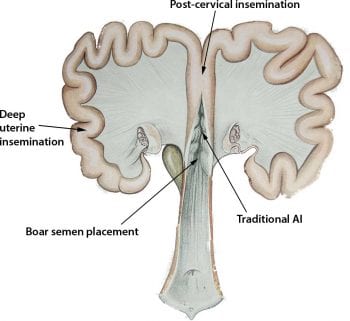

Producers should adopt systems that maximise the use of the best boars available. Two technologies are being exploited where boar utilisation can be optimised – single serving and post-cervical insemination.

This means that with effective heat detection, weaned sows in oestrus can be single‑served (inseminated once) on day five, six or seven post-weaning with results that are not statistically different from double‑served sows (Table 1).

The reduced number of sperm maximises the genetic impact of a particular boar, and the lower insemination volume means less “foreign” material is deposited into the reproductive tract – reducing pathogen spread risks – and takes less time to complete.

Figure 3 shows how using single serving and post-cervical insemination on one farm reduced the FCR by 0.16.

The COVID-19 pandemic has restricted movements to see clients to perceived essential visits, but veterinary surgeons must still ensure the welfare standards of the animals under their care are maintained.

The use of batching allows farms to be more organised into identical groups. It is easier to understand events unfolding on a pig unit today with the benefit of a good history and relevant data. The use of production boards is encouraged to ensure such information is always to hand and can be passed on photographically.

Two production boards are particularly useful:

The production boards reflect the batching concept. Targets are set and then the health team has to try to meet or surpass them.

The batching concept aims to eliminate variation in production on farms, allowing them to be productive and stay within the legislative welfare requirements.

A problem often arises with members of the farm team trying to hide production results (failures) to protect bonuses or even reputation – delaying euthanasia on a Friday or at the end of the month “because it ruins this week’s numbers” is a classic example. As veterinary surgeons, we need to coach our clients and their staff that such attitudes are short-sighted.

The use of production boards presented in real time should stop this sort of thing. It also helps to highlight issues, creates discussion and debate, and provides a teaching opportunity with the farm health team.

The number (proportion) of gilts in a batch is a vital number to know and understand. It influences the number of problems in the farrowing area and the post-weaning mortality.

Having the same number of females bred each batch removes a major variability, but having the same number of gilts bred each batch removes another significant trigger to deterioration in the health of the batch.

If a farm evaluation is being carried out virtually, the veterinary surgeon should introduce production boards and alarms, then train the farm health team to respond to health crises.

If the batch is in “alarm”, the farm health team immediately should:

The videos will provide remote inspection of the pigs, but also valuable insight into the husbandry of the system, including the water, feed system and flooring (Figure 6). An impression of the air quality and ventilation systems is more difficult to infer from a 30‑second video clip, but the lying and defecation patterns will help.

This allows the veterinary surgeon to determine the likely cause of the problem, possibly instigate further investigations and may necessitate a visit to the affected site.

After 20 years of trying to get a system of intradermal injection into general practice, we are almost there.

A number of pathogen vaccines are now available that can be administered via the intradermal route rather than IM. This eliminates the need for a needle, which enhances the meat safety and human health and safety of vaccination. The vaccination programme also requires less training.

The injection can be administered anywhere on the pig’s skin, which acts as one large immune organ. The skin offers a new frontier in vaccinology to improve the health and well‑being of our pigs.

Previously, the neck of the pig was less valuable as meat; however, with the globalisation of meat supply, all of the pig is now valuable. The Chinese love our pig neck joints.

As pig farms move progressively towards antibiotic-free farming systems, many pigs may never have to experience the discomfort of receiving an injection. This would be a major milestone in veterinary history.

The spread of the African swine fever (ASF) virus pandemic into China and south-east Asia since 2018 – and now Germany – has resulted in a catastrophe on a biblical scale for the human meat protein source.

A loss of 300 million pigs would equate to a loss of 10% of the global meat supply. To put this in perspective, to replace this loss of meat would require a increase in the number beef cattle on this planet by 40%, or a 25% increase in the number of chickens, which is unlikely.

COVID-19 has diverted man’s attention away from veterinary issues. This may well have put back vaccine research into ASF virus by many years. Nevertheless, it is likely the ASF pandemic (Figure 7) will be with us long after COVID-19 has faded into the background.

The role of veterinary surgeons in maintaining health on clients’ farms has to focus on the biosecurity of the farm. This requires a major shift in the focus of the veterinary coach.

The veterinary surgeon needs to think like a pig and enforce the perimeter security of the farm (Figure 8) to eliminate the risk of the incursion of live pigs, pork or pig faeces.