2 May 2023

David Charles BVSc, CertHE(Biol), MRCVS provides a comprehensive guide to carrying out this procedure in sheep, which requires more than just surgery.

Ovine caesarean sections are commonly performed by practitioners nationwide, and the surgical approach is well-documented across the board from university lectures to practical CPD courses, and several well-respected production animal textbooks.

In this article, we will consider “everything but the surgery” (including common causes, preoperative medications and post-procedure management), while reviewing the evidence to help practitioners make the best evidence-based veterinary medicine decisions and, ideally, maximise their success rates for this procedure.

With an increasing trend for advancement or synchronisation of the ovine breeding season (for example, with progesterone-releasing devices or laparoscopic AI), we are seeing lambing season start earlier each year as clients look to gain the management and financial benefits of lambing earlier in the season (the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board [AHDB] reports as much as 21% higher prices based on overall SQQ (standard quality quotient) in 2022 for early new season lambs compared to July/August prices; AHDB, 2022).

With clients investing more into getting ewes pregnant, and a rise in lamb prices over the past few years, many clients are justifying the cost of caesarean sections. This article will look at the practical considerations for the ovine caesarean section beyond just the surgical technique, which is detailed well in several articles and textbooks.

Caesarean sections are commonly performed on farm; however, it is worth noting that many practices offer the facilities for clients to bring ewes to the practice to undergo caesarean section and other obstetrical procedures. This can provide a cheaper service to clients (often forgoing the call-out/visit charge) and allows an individual practitioner to increase the number of animals seen in a short space of time during busy lambing seasons by negating the driving time of the practitioner.

If sheep are brought into the practice, it remains vitally important that any examination room surfaces and equipment are adequately disinfected between clients, and any biological waste is appropriately disposed of – especially considering the zoonotic potential of many pathogens encountered during lambing season and the risk to other clinical and non-clinical practice staff (for example, admin staff and cleaners who may not be aware). In some cases, clients will call for an elective caesarean, and in others, veterinary-assisted vaginal delivery (VD) will have been attempted first. Either way, suitable PPE and disinfection on arrival should be performed.

If veterinary-assisted VD has been attempted first then fresh PPE should be used prior to caesarean section (as a minimum a new, freshly laundered parlour top and gloves) or a disposable surgical gown should be used. Key history questions are outlined in Panel 1.

Recent studies have shown survival rates to be favourable, with 89.2% (Hawkins et al, 2021) and 94.8% (Charles and Stockton, 2022) of ewes surviving without any postoperative complications seven days post-procedure and, therefore, a favourable prognosis can be given.

Concurrent disorders such as severe ovine pregnancy toxaemia, significant uterine tissue damage (suspected tears from previous delivery attempts) and cachexia were proven to decrease ewe-survival rates, with Voigt et al (2021) reporting concurrent disease could reduce ewe survival rates post-procedure to as little as 68.5%. However, their same study concluded that dead or emphysematous fetuses had no impact on ewe mortality, in contrast to Scott (1989), who saw survival rates reduce to 57% with an emphysematous fetus.

All three studies included a number of “casualty caesareans”, whereby ewes were euthanised immediately after removal of lambs on welfare grounds, due to a pre-existing condition in the ewe, in an attempt to preserve the viability of the lambs close to term and to reduce financial losses to the client.

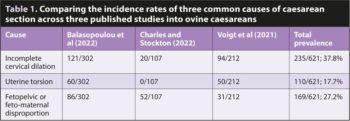

Incomplete cervical dilation (ICD), uterine torsions and feto-maternal disproportion are common causes for caesarean section in cattle (Alexander, 2013), and this is also the same in sheep.

Table 1 shows the prevalxence of these as reported in three recent studies (Voigt et al, 2021; Balasopoulou et al, 2022; Charles and Stockton, 2022).

In the author’s joint study of 209 ovine dystocia cases across several practices within the IVC Evidensia UK and Ireland group in the 2021-22 lambing season (Charles and Stockton, 2022), it was found that while ICD led to 18% of recorded caesarean sections, very few practitioners had administered intramuscular denaverine hydrochloride to assist in correction of the ICD.

With Voigt et al (2021) and Balasopoulou et al (2022) recording cases presented between 2008-19 and 2008-21 respectively, it is likely few patients in their studies received denaverine hydrochloride either, with it being a recently licensed product in the EU (first licensed as Sensiblex; Kela Health in 2017; Kela Animal Health, 2017).

Denaverine hydrochloride is licensed in cattle for dilation and analgesia of the soft tissues of the birth canal (Health Products Regulatory Authority, 2017) and the manufacturer claims it has efficacy in dilating the ovine cervix in cases of ringwomb or ICD.

The author’s practice has successfully used denaverine hydrochloride in cattle and sheep over the past few years, and this may be a product that practitioners wish to consider for future lambing seasons – especially as administering it and performing an assisted VD may see large economic benefits for clients. Practitioners should note that use of denaverine hydrochloride in sheep is under the prescribing cascade and appropriate minimum withdrawal periods should be followed (VMD, 2021).

Aside from the potential use of denaverine hydrochloride, other perioperative medicines can be administered prior to commencing surgery. Suggested doses and withdrawal periods are recorded in Table 2.

NSAIDs should always be administered to sheep undergoing surgical intervention, with preoperative administration recommended, followed by an ongoing postoperative course of a minimum of three days. No licensed NSAIDs remain in the UK and, therefore, any product use is under the cascade – and appropriate off-licence consent should be gained.

It is worth noting that meloxicam is licensed in Australia, New Zealand and Canada at the 1mg/kg dose, which is different from the cattle dose and, therefore, the author recommends this dose is used in sheep in the UK. Flunixin meglumine and ketoprofen can also be used, and when it is, the cattle dose is generally advised. Uterine relaxants such as clenbuterol can be administered off licence; however, much debate remains among sheep practitioners regarding its success in sheep compared to cattle.

Antibiotics can be justified, as ovine caesarean section is at best a “clean-contaminated” surgery. Historically, practitioners may have reached for procaine penicillin and dihydrostreptomycin sulfate; however, with a need to ensure responsible use of antibiotics and considering the European Medicines Agency (EMA) categorisation (EMA, 2022) of combination penicillin and dihydrostreptomycin products into category C “caution” antibiotics, the author would urge practitioners to select for category D “prudence” products such as amoxicillin or benzylpenicillin, which are licensed for sheep and have activity against the usual pathogens encountered (“mixed” coliforms, most commonly).

An epidural might have already been administered if the practitioner has attempted fetal repositioning for assisted VD; however, if not, it should be considered during patient preparation for caesarean section. It is the author’s belief that sacrococcygeal epidurals are now commonly performed by practitioners carrying out bovine caesarean section, but less frequently used for ovine caesarean section.

In their review of the evidence, Phythian et al (2019) give a balanced argument for and against the use of the sacrococcygeal epidural, considering the benefits (increased pain relief and ewe comfort alongside decreased abdominal straining) and potential risks (impact on ability of lambs to access colostrum and potential for short-term ataxia).

The equipment required is detailed in Panel 2, and while variation exists within the literature for dosages (Hodgkinson and Dawson, 2007; Galatos, 2011; Wood, 2019), the author advocates for 1ml to 1.5ml of procaine hydrochloride with an optional 0.1ml to 0.25ml 2% xylazine if indicated (however, it is also worth noting that “spiking” the epidural with xylazine 2% may increase ataxia postoperatively and, therefore, clients will need to pay increased attention to ensure lambs can access the udder to receive sufficient colostrum).

The local anaesthetic alone will provide approximately four hours of epidural anaesthesia, while the addition of xylazine 2% extends the duration to 24 to 36 hours (Galatos, 2011), and is particularly recommended in prolapse replacement or ewes that prolapse during VD attempts.

In the clinic, ewes can be restrained on height adjustable surgical tables held by the client/a member of staff (Figure 1), or some tables incorporate straps to restrain small ruminants on a rollover table. “In the field” options tend to be limited and, most commonly, restraint necessitates the ewe held in right lateral recumbency on a clean bedded pen (Figure 1), bale or pallets.

Practitioners may wish to consider their posture and backs when selecting; after performing several on freshly bedded pens, the author now advocates for elevated restraint on a table, bale or pallet to reduce the impact on the practitioner’s body by the end of a busy lambing season (Figure 2).

A wide clip patch should be made to allow for the surgical site to be appropriately far away from the wool: the body wall has a tendency to “drop down/in” after removal of the lambs, which can increase the risk of wool contamination if clip is not large enough.

A good clip will leave the suture line a good distance from the wool edges to prevent contamination during wound healing (Figures 3 and 4).

The surgical site should be scrubbed with chlorhexidine gluconate solution or povidone iodine solution.

Significant care is required with respect to exceeding reported toxic doses of procaine hydrochloride in sheep, with a range of 5mg/kg to 10mg/kg reported as a toxic dose (Galatos, 2011; Phythian et al, 2019). To avoid this, a 1:1 dilution with water for injection can be performed (Mueller, 2017) and selection for line block over inverted-L will reduce volumes used, yet achieve appropriate loco-regional anaesthesia (Thorne and Jackson, 2000; Scott, 2015).

For ease of administration, the author administers diluted local anaesthetic for the line block via a calibrated vaccination gun, with a fresh sterile needle for consistent administration.

Practitioners must also note that not all procaine hydrochloride and adrenaline products commonly used in the UK are licensed for sheep and a 28-day minimum withdrawal period should be applied alongside gaining off-licence consent.

Appropriate asepsis for surgery should be achieved through the use of a surgical scrub (chlorhexidine or povidone iodine) or an alcohol-based hand rub. The author advocates for the use of sterile surgical gloves for this invasive surgical procedure to protect the patient from environmental contaminants, and the surgeon from irritants such as uterine fluid.

The majority of practitioners in the UK select for the left-sided paralumbar approach, which is well described in the literature (Scott, 2015; Weaver et al, 2018; Phythian et al, 2019) and as such, is felt to be beyond the scope of this article.

The other approach practitioners may consider is the ventral paramedian approach – a technique that is more commonly used in the southern hemisphere. The approach used should be one the surgeon is confident and competent at, and Downes and Dean (2014) found that if this is the case, no significant variation in ewe mortality or lamb viability has been proven.

Panel 3 lists the author’s recommended equipment for ovine caesarean section.

After successful closure of the patient, it is important to consider both the ewe and the lamb(s). Ideally, an assistant or member of farm staff would be able to check the lambs and assist in revival during closure of the ewe.

Methods such as nasal stimulation with straw, manual clearing of the airways, lamb ampu-bags and products such as energy booster paste (containing glucose, caffeine and selenium; the author advocates for the use of Nimrod Red Start) can aid in getting the lamb(s) going.

Positioning of the lamb can also aid respiratory intake by placing in sternal with the forelimbs tucked underneath (Figure 5). Placing the lamb(s) by the ewe’s head will also help with mothering and the maternal bond.

While the ewe is recumbent, it is wise to check the udder for expressible colostrum. If any doubt exists then advising the client to supplement is recommended; lambs require 50ml/kg within the first two hours of life and 200ml/kg within 24 hours.

Postoperative care of the ewe should include an appropriate length course of antibiotics and NSAIDs. Oral fluids can be given as well, to increase energy in the ewe (the author’s standard approach, if no complications are observed in the procedure, is to leave a bucket of rehydration powder [the author advocates the use of Nimrod Selekt Restore] with 60g in a 3L bucket of water).

Clear advice to the client regarding medication doses and timing should be given, as well as suture removal (if non-absorbable skin sutures are used) and what to look for postoperatively (for example, wound swelling, wound breakdown or discharge, retained fetal membranes). The author has taken to photographing the surgical site at the end of the procedure to give a reference should the client report any changes or potential breakdown.

The author chooses to perform postoperative telephone calls one and four days post-procedure to check on the client, ewe and lamb. Although sometimes, these are not needed if you find yourself on the same farm the next day for another obstetrical case, as you can then see your patient in person.