27 Feb 2017

Lee-Anne Oliver provides guidance on this procedure, including working with farmers and what signs to look out for.

Changes in the provision of subsidised surveillance postmortem examinations across England and Wales in the past few years have meant many veterinary practitioners have been faced with the prospect of carrying out their own postmortems either on farm or at a local dead stock collection centre.

Although there can be great value from carrying out a postmortem, it is not always an easy task. A number of hurdles that need to be overcome are:

Communicating to the farmer how his or her input can help you do a thorough job in difficult circumstances can help the postmortem to be safe, require minimum physical effort, incur minimal cost and give the best chance of reaching a diagnosis.

A postmortem can be a daunting concept with a farmer watching, for even the most experienced vets; correctly interpreting pathology, collecting the correct samples, deciding what is significant, or which lesions are due to autolysis. A number of providers offer good quality, hands-on CPD, but, ultimately, confidence comes from practise. Most diagnostic laboratories offer advice over the telephone and it is worth developing a relationship with one so someone is always available to telephone. A good clinical history and photos of any pathology can be used to obtain help from a distance.

Having highlighted the negatives, a huge amount can be gained from gross postmortems. In a study at a dead stock collection centre in County Durham, 106 postmortem examinations were carried out on adult ewes without clinical history. Further laboratory testing was carried out where a diagnosis could not be confirmed.

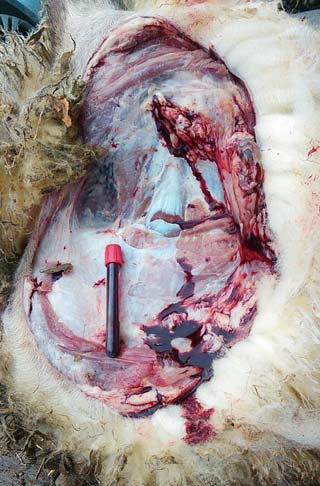

A diagnosis considered significant enough to account for death was reached in 74/106 cases. In 9 cases, autolysis precluded a meaningful diagnosis and, in 38/74 cases, diagnoses were made on gross pathology alone. The diagnoses made from gross pathology included dosing gun injury, acute and chronic fascioliasis, poor dentition, peritonitis, abdominal torsion, endocarditis and obstetrical catastrophes. All of these are detectable by vets with basic pathology training and the information can be used to educate, carry out further testing and implement change for the better on farm. Further testing was required to reach a definitive diagnosis in cases of ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma and Johne’s disease, which are valuable diagnoses at flock level (Lovatt and Strugnell, 2013; Figure 1).

So, after managing to persuade the farmer to allow you to carry out a postmortem, explaining the limitations of a gross postmortem and making the area safe with suitable equipment and manpower to help you do a good job, what is the next step?

It is beneficial to have a full clinical history and knowledge of the farm before attempting the postmortem. With this information, a short list of differentials can be compiled. For example, a six-week-old Suffolk lamb with a dirty perineum is the third to die in the group in the past three days.

The ewes are not vaccinated against clostridial disease (Figure 2).

Differentials, in no particular order, include:

This immediately focuses the mind on the different organ systems, the pathology that may be present and any samples required to confirm a diagnosis, if required. No right or wrong way exists to carry out a postmortem, but the examination should be consistent and systematic. If any organ system is not examined, this should be documented. In many cases this will be the brain.

If additional testing is required to reach a diagnosis then sampling is required. Often, additional testing can be carried out in house, with little additional cost. For example, urine can be tested for the presence of glucose, where clostridial disease is suspected, using a urine test strip.

A handheld pH meter can be used to obtain rumen pH where acidosis is suspected. A pH of less than five is suggestive of acidosis, although pH will increase over time and become more alkaline the longer the animal has been dead. A faecal egg count and coccidial oocyst count is often useful, although must be interpreted with caution as the nematode or coccidial infection may be prepatent. Biochemical analysis of ocular fluid for calcium, magnesium, betahydroxybutarate and urea can be useful in cases of hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia, ketosis and nephrosis. Vitreous humour is more stable for magnesium levels up to 48 hours after death.

In cases where additional testing is required at an external laboratory, care should be taken to send the correct samples, delivered in suitable containers to the laboratory. Packaging should conform to P650 packing instructions for transportation of biological substances. Completing the submission form fully allows the laboratory to provide the best possible service and carry out surveillance, including new and emerging diseases. Often, a quick telephone call to the laboratory to discuss the case can be beneficial; a few testing options may be available – the laboratory can help you to take the right samples, with the most chance of achieving a diagnosis, with minimum cost.

Regarding calf diarrhoea:

In terms of serology:

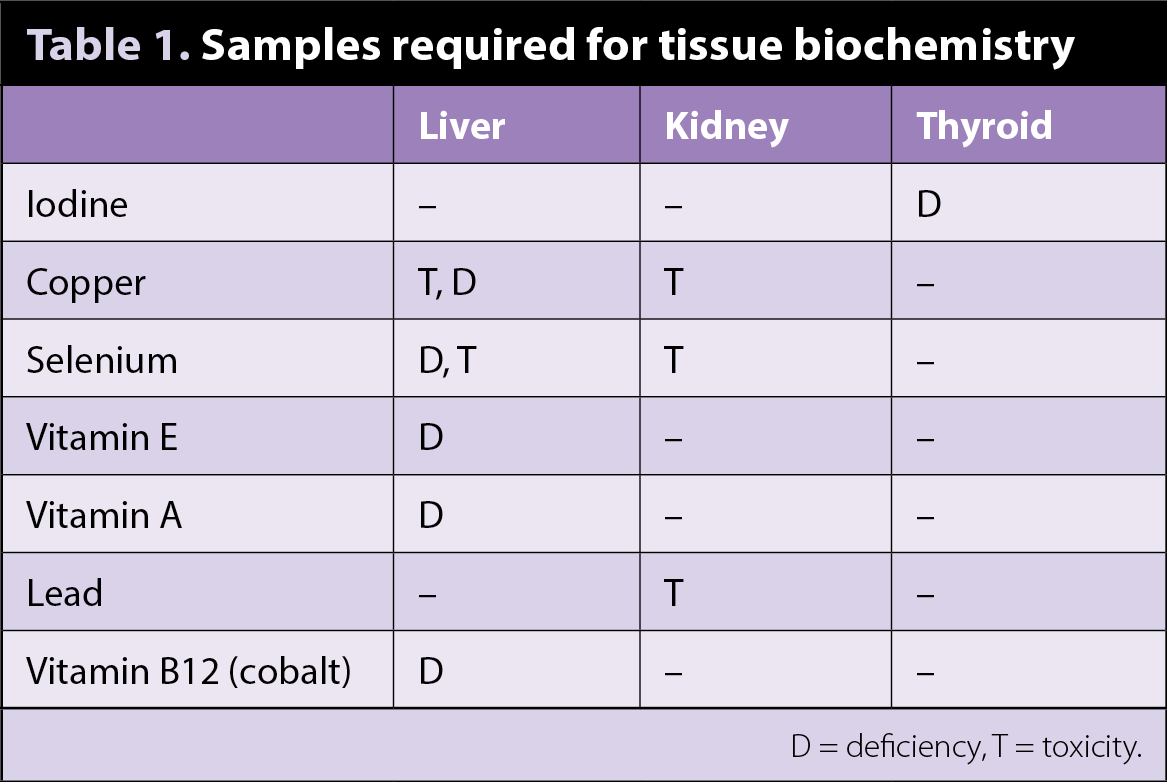

Regarding tissue biochemistry:

Ideally, bacteriology is the preferred method to detect Pasteurella species, Histophilous somni and Mycoplasma infections.

Often, bacteriology is not possible if the carcase is severely autolysed or samples can not be delivered to the laboratory promptly. Even with good sample selection, a mixed growth involving contaminants may mask a significant pathogen; therefore, storing samples in formalin and taking fresh lung for PCR is recommended, in addition to bacteriology, where possible.

Samples should be taken from the advancing edge of the lesion. PCR testing is available for respiratory syncytial virus, bovine parainfluenza virus type-three, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica and H somni. Multiplex PCRs should be interpreted with caution as to the significance of a positive result. Pasteurella species are often commensals of the respiratory tract. A 1cm3 piece of lung is required, ideally in viral transport media. This can be frozen and thawed for analysis later, if required.

Recording the gross pathological – and subsequent testing results – for a postmortem as a written report serves as a document for the farmer and the vet. For the farmer, it adds value to the postmortem examination and, if photographs are included, helps the farmer visualise the extent of the pathology. For the vet, it serves as a record for future reference, for example, when carrying out a herd health plan review.