15 Aug 2023

Owen Atkinson BVSc, DCHP, MRCVS emphasises the crucial role vets play on this issue, and how they can be better involved in ensuring safe dairy products.

Image: © Laurent Renault / Adobe Stock

Milk is an important component of the human diet and plays a crucial role in growth and development. For consumers to be able to buy milk and dairy products with absolute confidence they are safe is phenomenally important. This includes that it contains no medicinal residues that could cause harm.

Vets, as the ultimate guardians of veterinary medicines on dairy farms, are absolutely vital in the chain of responsibility to ensure this safety.

This article aims to explore the significance of veterinary medicine residues in milk, the potential sources, detection methods, and ways to ensure milk quality and safety, highlighting the MilkSure programme in the UK.

Milk residues refer to the presence of substances or compounds that are not naturally occurring or intentionally added to milk or milk products. These residues can arise from various sources, including medications, chemicals, pesticides, environmental contaminants and improper agricultural practices.

Veterinary medicines administered to animals – such as antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs and anthelmintics – are potential contributors to milk residues. This article is concerned with these potential medicinal residues.

When administering veterinary medicines to lactating animals, a risk of residues appearing in the milk exists.

Every medicine with a marketing authority (MA) to be used in dairy cows (that is to say, licensed) will have safety data to support its use. This will include a permitted maximum residue limit (MRL), which will be specific for milk and will have been calculated after careful scientific methodology based on likelihood of harm.

Some medicines must never be used in milk animals, either simply because this safety work has not been done, or that it has been done, and no residue can be considered “safe”.

Some go-to examples here include phenylbutazone, which can cause life-threatening blood dyscrasias in humans even at low levels (Lees and Toutain, 2013) or closantel – a flukicide that can be used in some dairy youngstock, beef and sheep, but not animals producing milk for human consumption.

Closantel can concentrate in milk fats and is neurotoxic to humans – symptoms of which can include irreversible optic disc atrophy (Venkatesh et al, 2019).

Yet, both phenylbutazone and closantel may be available to dairy farmers in medication legitimately prescribed for other purposes.

So, this brings us to the foremost important point: never turn a blind eye to or facilitate the use of medicines in the dairy herd (which includes cows during the dry period) when they do not have an MA to be used. Always ensure prescribed medicines are used only in their intended target animals.

Keep alert to medicines that may have been prescribed and supplied by others, too, including SQPs and animal health suppliers.

So, while medicine licensing begins with establishing an MRL (a safety dossier), the next thing to consider is how long after a course of treatment should the milk be discarded.

This is the withdrawal period, the calculation of which requires a ‘residues dossier’ to be established for that product.

The withdrawal period on the MA, and which is included in the data sheet, is the minimum period, and it can only be considered sufficient as long as the medicine was used according to the recommended dosage and treatment regime, including, for example, the route of administration.

Swiftly, the second-most important point: never turn a blind eye to or facilitate the use of medicines in the dairy herd when they are not used in accordance with the data sheet. A very common example here is the extended use of mastitis antibiotic tubes. To do so would require prescription under the cascade, and a different minimum withdrawal period. More on that forthcoming.

In summary, it is crucial to only use licensed medicines and then to follow the data sheet dosage recommendations, and then the prescribed withdrawal period to allow the medications to metabolise and eliminate from the animal’s system before consuming its milk. Here endeth the lesson – but not quite, as will be seen.

While purposeful incorrect use of veterinary medicines – in terms of medicine used, dose rate and application of withdrawal periods – is an important potential cause of milk residues, it is not the most common reason.

Human error, poor record keeping, forgetfulness, vagaries of cows moving between groups (for example, from dry cow pen to milking cow pen), cows calving early and mechanical failure are all actually more usual reasons for finding residues.

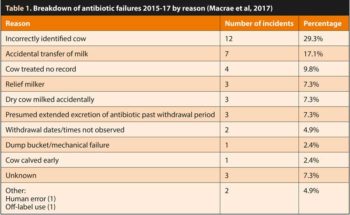

A careful and logical investigation of all failures should always be completed to find the cause. Macrae et al (2017) investigated 41 fail events in a relatively small producer group between 2015-17, and the results are shown in Table 1.

This lists 11 potential failure-of-procedure categories – the most common of which was incorrectly identified cow. In fact, even this list is very much truncated. Vets undertaking MilkSure training will know that more than 30 potential failure categories exist for residues.

To avoid these, a hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) approach is advocated. This is integral to delivering the MilkSure programme on farms.

Keeping treated cows (and under withdrawal period) separate from the main herd will help mitigate the risk for several of these categories. While this is something done de rigueur in dairy herds in many other countries, such as the North Americas and the Antipodes, it is not practised across the board on UK dairy farms.

As farms become larger, with a greater number of personnel involved in milking, the rationale of having entirely separate treatment groups, and these cows being milked last (or even through a separate parlour, in very large herds) becomes even more compelling. It will only be effective, however, if the treated animal is first recorded, correctly identified and actually moved. Ideally, this all occurs before the treatment is administered – not afterwards.

During MilkSure-for-Vets training workshops, often the biggest area of confusion and uncertainty that comes to light for delegates is the use of cascade prescribing.

Some vets are not aware of how much responsibility they take on themselves when prescribing using the cascade, including the setting of appropriate withdrawal periods and record keeping requirements. Others may be unclear when it is appropriate to use.

It is worth, then, saying a few words here about the cascade in dairy practice.

As a generality, the cascade allows vets some flexibility to prescribe outwith the MA of a medicine.

It is useful, for example, for minority species, where few licensed options are available. It is not really designed for routine use in dairy herds, where generally, lots of licensed treatments are available.

To even consider using the cascade for food animals, certain criteria must be met. These are:

The product must (author’s emphasis) be on a list of approved medicines. In general terms, for vet medicines, this means an MRL will be established at least for some class of food animals.

The vet must prescribe the medicine on a case-by-case basis. It cannot be a general protocol.

The prescribing vet must keep a record of the prescribing event and include the identity of the animal(s), and the reason for using the cascade in this instance.

The prescribing vet must be able to justify using the cascade. While some exceptional and closely defined circumstances exist when it is okay to do so, this generally means that if a licensed alternative is available, cascade prescribing should not be used.

Farmers who use medicines outside the MA without specific veterinary say-so – and without the vet following these criteria – are acting unlawfully. It is not cascade use without specific veterinary authorisation, and if it is “off label” and not cascade, it is illegal.

To remain legal when using medicines, and under close veterinary stewardship, is very important in safeguarding not only animal health and welfare, but also food safety. A lot of farmers will not know they are acting illegally if they, for example, prolong a course of treatment or use the wrong dose, of their own volition.

You might call this “unknowingly unknowing”. Vets have a big responsibility to correct this, and probably pleading ignorance (of the farmer’s ignorance) would not be a strong defence should something go wrong.

More than 100 dairy processors exist in the UK. The big two are Arla and MÜller, and between them they supply the majority of milk sold in supermarkets, as well as manufacturing many other dairy products. Some smaller ones are well known, due to their brand, but actually account for very little of the overall UK milk pool; for example, Rodda’s dairy (of clotted cream fame). Many will not be well known to vets outside the geographical region they operate.

In addition to these processors, some farmers sell direct to the public – either via a milk round or (increasingly) vending machines.

So, the policing of milk residues is potentially very complex. In fact, all registered processors must have a risk-based approach to testing milk they collect. Typically, this involves testing around one in seven collections for antibiotics using an inhibitory substance test (commonly, Delvo).

This is almost entirely subcontracted to National Milk Laboratories, as they also test nearly all of the collected milk in Great Britain for quality (butterfat, protein, cell counts, bactoscan and so forth), on which payments are based. Some milk buyers – arguably the most responsible ones – test every single collection.

On top of this bulk tank testing, regulatory requirements mean that every milk tanker must be tested before the milk can be used. This is done at the factory, before unloading, using a variety of different rapid immune assays – some of which have very narrow spectra (just beta-lactams) and others a bit more broad. Although they vary, they are all reasonably sensitive screening tests, but by this stage, the milk has already been diluted, and so only a minority of reported fail events are discovered this way.

As an aside, dilution is not a solution when it comes to milk residues. It is technically illegal to sell milk from any single cow if a residue is above the MRL – regardless of whether, after dilution, the residue falls below the MRL.

In reality, though, dilution does give us a practical added safety net for most of us buying milk from, say, the supermarket. Perhaps less so when buying from a farm’s vending machine.

The screening tests used are predominantly for antibiotics. What about the other medicines? Again, variation exists between processors; for example, in Northern Ireland, milk is routinely screened for flukicides, and less so in Great Britain; although, that is changing.

Testing for a wider range of medicines is becoming ever more possible due to the development of more sophisticated immune assays with a much broader range of analytes available, including NSAIDs, anthelmintics and flukicides, as well as antibiotics. In addition to the processor-driven screening for antibiotics, which has been described, the Veterinary Medicines Directorate routinely tests bulk tank milk samples using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry methods.

This is expensive, and the results may take a week or more to come through, but it does mean that every farm selling milk to a processor may be subjected to this very sensitive test, which can detect every conceivable type of veterinary medicine.

Some farmers and vets, historically, have perhaps been used to an environment where they thought they could get away with residues of some medicines. This arguably led to some very bad practices in the past (for example, withdrawal periods not being adhered to; wrong doses being used; inappropriate medicines used).

Things are changing due to rapid advances in testing technologies.

Humans who consume milk or milk products containing residues may be exposed to potential health hazards. Antibiotic residues, for example, can contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance, which poses a significant threat to public health. Additionally, certain contaminants could have other detrimental effects on human health, including allergic reactions, neurotoxicity and carcinogenicity.

Beyond these important reasons, though, other more prosaic grounds to avoid residues exist. The reputational damage to the dairy industry should go without saying. If farmers (and their vets) expect people to continue buying milk, professionals must act to retain their confidence. This means playing by the rules, and having appropriate risk avoidance procedures and appropriate policing in place.

The cost of residues is not insignificant. Each year, millions of litres of milk must be disposed of due to residues. The cost of disposal is at least as costly as the value of the milk, as once the contaminated milk has been collected from the farm, it is classed as a category two animal by-product, and is usually incinerated (believe it or not).

Finally, as is sometimes forgotten, medicinal residues can severely interfere with the processing of milk. Think about the yoghurt, whose starter cultures are affected by small traces of antibiotic; or the matured cheese, which does not quite taste as it should due to an imbalance of bacterial cultures.

First things first: vets should carefully prescribe medicines and provide clear instructions regarding their use and the withdrawal periods to prevent milk residues.

Then, producers must strictly adhere to these guidelines to ensure milk from treated animals is safe for consumption.

No one has a right to have a medicine dispensed to them, and farm vets really must take their responsibility seriously about ensuring the farmer is competent and trustworthy to use it properly. If not, do not prescribe.

Over and above these basic responsibilities, the MilkSure programme has been developed to help farmers and their vets reduce residues. MilkSure came about in 2016, after the processors, represented by Dairy UK, asked for help in this area from the BCVA. The programme is, in part, a training programme, designed to upskill farmers in how to use medicines as they should. It is also a HACCP approach to reducing the risks on individual farms, based on a periodic risk assessment carried out by the vet working collaboratively with their farmer client.

Some UK farm vet practices have taken the initiative to ensure all of their dairy farms are MilkSure accredited. This is to be commended, and actually very sensible, too. Some dairy processors have done likewise: all of their supply farms must be MilkSure accredited. Other processors use it in a more ad hoc way – typically for the farms that have had a residue failure.

Overall, through MilkSure and other processor efforts, the rate of bulk tank failures has halved since 2016. This is a fantastic achievement.

The best outcomes have been seen by those processors that have made MilkSure accreditation compulsory. In addition, since 2016, more than 300 vets have undertaken MilkSure-for-Vets training, which allows them to understand the residue issue more fully, as well as to deliver the MilkSure programme on farm.

By itself, the training of vets appears to have done a lot to change prescribing behaviours, to use the cascade only where it is appropriate, and to ensure farmers stick more rigidly to treatment protocols.

This has led to less confusion all round and probably a more professional and responsible approach to medicine use on dairy farms now, compared with several years ago.

Avoiding medicine residues in milk is part of the farm vet’s role.

Clearly, vets cannot be entirely responsible for everything that happens on farm with relation to medicines and mistakes, but a responsibility exists to ensure the risks have been examined and the appropriate training has been given.

It is careless to make assumptions about farmers’ knowledge and understanding when it comes to medicine use. In the author’s experience, farmers very much value and welcome training and assistance in this area.

The MilkSure programme is the national and accredited approach to deliver this training and assistance, fully supported by the BCVA, Red Tractor, Dairy UK, and the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board.

Vets working with dairy farms are encouraged to engage with the programme and use it widely. Thereby, milk quality and safety can be further improved, and consumer trust maintained. Meanwhile, vets might sleep a bit more easily themselves, too.

To discover more about MilkSure and how to become a MilkSure registered vet, visit www.bcva.org.uk/content/how-milksure-works