12 Dec 2023

David Harwood reviews the Goat Veterinary Society’s latest conference, where an honorary life membership was also bestowed.

Metabolic profiling, which is useful for commercial dairy herds.

The Goat Veterinary Society (GVS) held its virtual autumn conference over two successive Wednesday afternoons in November, with delegate numbers peaking at around 70.

The first speaker was Sandra Baxendell, who, despite the time difference, spoke to the meeting live from Queensland, Australia. Dr Baxendell is a well-known and highly respected figure in the goat world with a strong social media presence as “goatvetoz”. During the meeting, GVS awarded her an honorary life membership in recognition of her outstanding contributions to goat health and welfare.

Back in 2013, goat sector representatives and vets met up to discuss control of caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE) across Australia. It was recognised that the condition confined predominantly within the goat dairy sector also posed a threat to the sheep sector in addition to the goat meat and fibre sectors, and also had significant health and welfare implications.

A series of new Market Assurance Programs (MAPs) were then developed covering general goat herd biosecurity, CAE and also Johne’s disease. These initiatives required individual and permanent identification of all goats, the development of a national database of all goat holdings and a general biosecurity plan developed with a participating veterinarian.

A very strict protocol was put in place on every holding requiring, for example, full disclosure of any goats that test positive or show clinical signs of disease, with potential loss of their MAP status.

The speaker then outlined the different levels of assurance within the schemes depending on testing protocols applied. Further information is available at https://animalhealthaustralia.com.au/goatmap

The second speaker was Alastair Macrae from The University of Edinburgh Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. He outlined the importance of considering all aspects of goat nutrition, with blood sampling being only one piece of the jigsaw.

From a practical perspective, the formulated ration on paper must then equate to the ration actually fed, the ration eaten, and what part of that is then digested and used. Consideration should then also be given to body condition, milk production and any concurrent disease alongside the planned blood testing programme.

Body condition scoring is best undertaken around six to eight weeks prior to kidding, with goats managed as necessary.

The speaker then described those diseases with a direct nutritional origin such as pregnancy toxaemia, ketosis, hypocalcaemia and selenium/iodine deficiency. Nutrition can also influence kid birthweight and reproductive efficiency.

Blood testing focuses on assessing energy efficiency through measuring beta hydroxybutyrate and non-esterified fatty acid, protein via urea, albumin, total protein and globulin. Mineral assay includes calcium, magnesium, phosphorus copper and selenium.

The speaker admitted that the sampling protocols and interpretation tend to be extrapolated from dairy cows, but data on metabolic profiling of dairy goats are increasing. Sample selection should include early and mid-lactation groups with a further group including late pregnancy. Group size should be between 5 and 12. One basic rule is not sampling until two weeks after any major diet change.

The next speaker was Al Manning of Quality Milk Management Services. He defined milk quality as a “measure of suitability for the consumer” and includes bacterial content, composition, cell count, appearance taste and smell. From available data for goats, mean fat was 4.6%, protein was 3.61% and lactose 4.65%.

Moving on to bacteria in goat milk, this is covered in EU legislation via EC 853/2004 (non-bovine milk), stating that milk for human consumption should be less than 1,500,000 colony forming units/ml. This figure is very high, and producers in the UK achieve far lower levels. These bacterial levels are particularly important, however, as some such as thermoduric bacteria can survive pasteurisation and impact processing; others such as psychrotrophic bacteria multiply at low refrigeration temperatures and can cause product spoilage.

Assessment of bacterial levels in milk may vary depending on where sampled, and may originate on farm (goats and farm environment), the dairy (collection vehicles, processing equipment) or at the consumer end in the retail outlet or home. Moving on the somatic cell counts, in generic terms, these are made up of mainly neutrophils, but also macrophages and lymphocytes.

The counts are generally much higher in goats than dairy cows, and this is generally thought to be linked to the physiological mechanism of milk production being apocrine (as opposed to merocrine in cattle) and counts will include these cell fragments.

A question often asked is whether goat’s milk is healthier than cow’s milk – the fat content is similar in both, but goat’s milk contains smaller fat globules, and this may make it more digestible. Goat’s milk also has a different balance of casein proteins to cow’s milk, so may be a good substitute for individuals with allergies to cow’s milk.

The first speaker on the second day was James Crilly of the RVC, who brought the audience up to date with new developments in this field. He began by outlining the alarming increase in anthelmintic resistance since early trials in 1992, with 100% of sheep flocks sampled in surveys in Wales and the south-west showing resistance to benzimidazole and ivermectin groups.

Less information is available in goats, although worldwide it is a recognised and increasing problem. In the UK, most dairy goats are housed, so parasite problems are more likely to be encountered in smaller hobby herds. Worm control measures will always be a local issue, varying not only from farm to farm, but also field to field on individual farms.

A number of trials and surveys have looked at breeding for resistance, with pygmy goats, for example, known to be more resistant to worms. Considering vaccine development, we currently have Barbervax for Haemonchus contortus, and with increasing knowledge of resistance mechanisms, others may follow. Research is also ongoing into bioactive forages that may reduce egg hatching rates.

Ruth Dalton, a livestock and wildlife specialist, was the next speaker. The speaker and her husband farm in Cumbria, and from day one have placed biodiversity at the heart of their enterprise. Their farm had large areas of bracken-covered land with wet areas and had only been grazed previously by sheep.

Their aim was to improve the land by encouraging a diverse plant population such that some plants will cope better when the conditions are dry; others when the land becomes waterlogged. This, in turn, will also encourage selective feeding – a particular trait of grazing/browsing goats.

The goats themselves (plus cattle that also co-graze) will also be spreading seeds in their faeces from field to field as they graze and move. They deliberately chose golden Guernsey goats, not because they were the ideal breed, but their offspring demanded a higher price, and profitability was still an important issue. Goats do kid indoors, but the herd will stay outdoors all year round with moveable shelters such as a horse box.

The speaker had noted that although the first arrival goats did run for shelter as soon as it rained, successive populations do appear to be developing tolerance to getting wet. The speaker has also noticed a big increase in small bird populations since taking over the farm, while badger and hedgehog numbers have also increased. Advice on this approach to farming is available from local wildlife trusts, ecologists and local farming networks.

The next speaker was Ben Dustan, current GVS president and in practice in Cumbria. Most medicines in the UK are unlicensed for use in goats, but are used under VMD cascade principles.

The most used agents for anaesthesia are xylazine, ketamine, butorphanol, detomidine and procaine/lidocaine. With local anaesthesia, the speaker recommends diluting 50:50 with sterile water and keeping the overall volume as low as possible.

The patient environment must be clean, warm, light, dry and draught-free. Patients must be kept in a stress-free environment, with pen mates in view, and with minimal restraint when handling (goats will stand quietly for a caesarean section as an example).

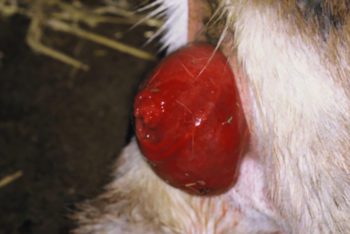

Reproductive tract prolapses were less frequently encountered than in either cattle or sheep, but are dealt with in a similar way, retaining with a Buhner suture.

Other techniques covered included castration and digit amputation. Digit amputation is useful for salvage purposes, and also a technique to use in high-value or pet goats, but the speaker did emphasise the importance of monitoring progress over time. He finished by describing a remarkably successful hindlimb amputation in a young goat kid with upper limb pain and non-weight bearing.

Former veterinary advisor to the Welsh Government and GVS committee member Les Eckford then reminded the audience that, despite Brexit, current animal health legislation is still built on previous EU rules.

Although legislation is similar across all four countries, devolution has led to some subtle differences, but this does not apply to either veterinary medicines or the Veterinary Surgeons Act that are consistent across all home nations. He emphasised the importance of knowing where goats and other livestock are kept, explaining how landholding reference numbers are applied. Equally important is the legislation incorporated into the Sheep and Goat Registration, Identification and Movement Order (2009) – and this applies to all goats whether kept for profit or pleasure.

Keepers are responsible for reporting movements of goats on and off holdings, markets and to slaughterhouses. Owners also need to be aware of their responsibilities under the Animal Welfare Act 2006, which sets out the welfare needs of all kept animals.

Vanessa Swinson of the APHA rounded the day off with a summary of the current situation in Europe, where bluetongue virus (BTV) serotype 3 has been identified and has been spreading in the Netherlands, and more recently in Belgium and Germany.

This is the first time infection has been confirmed in northern Europe since 2009 when the serotype was BTV8. However, BTV8 has recently been identified in France. The overall risk of BTV arriving in the UK is currently described as “medium,” although the onset of cooler weather will help.