11 Sept 2017

Owen Atkinson reviews some aspects of mastitis control at drying off and through the dry period, including immediately after calving.

Mastitis treatment and prevention accounts for the largest reason for antibiotic use on most UK dairy farms (Brunton et al, 2012).

The dry period is an important time to consider mastitis management, even though actual clinical cases are, obviously, mainly encountered during lactation (Green et al, 2002). A focus on this period has potential to reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in dairy farms, which is an important aim for safeguarding against the growing threat of antibiotic resistance (Kuipers et al, 2016; O’Neill, 2016).

When the author qualified as a vet (and it wasn’t that long ago), the dry period was barely considered when tackling mastitis cases – beyond, that is, using antibiotic dry cow therapy for all cows to help control cell counts (Bradley, 2002).

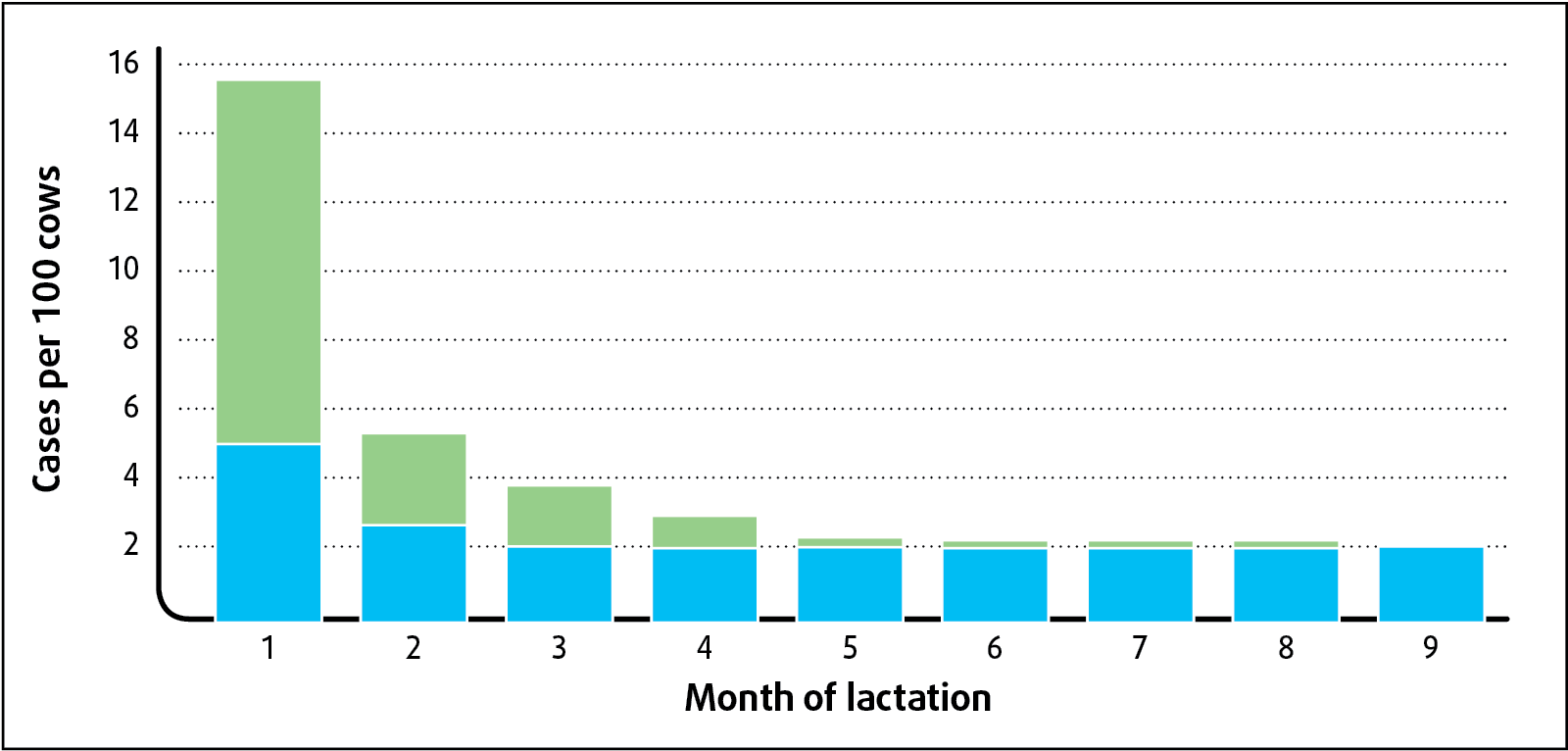

Subsequently, it has been found perhaps 40% or more of clinical cases stem from dry period infections (Green et al, 2002), in particular those of environmental origin, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and many Streptococcus uberis infections (Figure 1).

Now, the dry period seems to be the first place to focus on when dealing with farms’ mastitis problems. Sometimes, perhaps, this may be to the detriment of continuing to look at the other areas, such as teat damage, teat preparation, milking routines, bed hygiene and milking machine function – all still important areas, but in danger of becoming a bit out of fashion.

Meanwhile, considerable mindset change has taken place about the use of blanket antibiotic dry cow therapy. Selective dry cow therapy, while requiring careful risk management and cow selection, should now be considered a far superior approach, not only due to the reduction in unnecessary antibiotic use, but its potential to further reduce clinical mastitis rates in the following lactation (Bradley et al, 2010).

When, as a profession, we have been banging on to our farmers for nearly 50 years about the importance of all cows receiving dry cow antibiotics as part of the “five-point mastitis control plan” (Dodd et al, 1969), it might take a little while to persuade clients that times have moved on and newer, better ways of approaching dry cow therapy are now available.

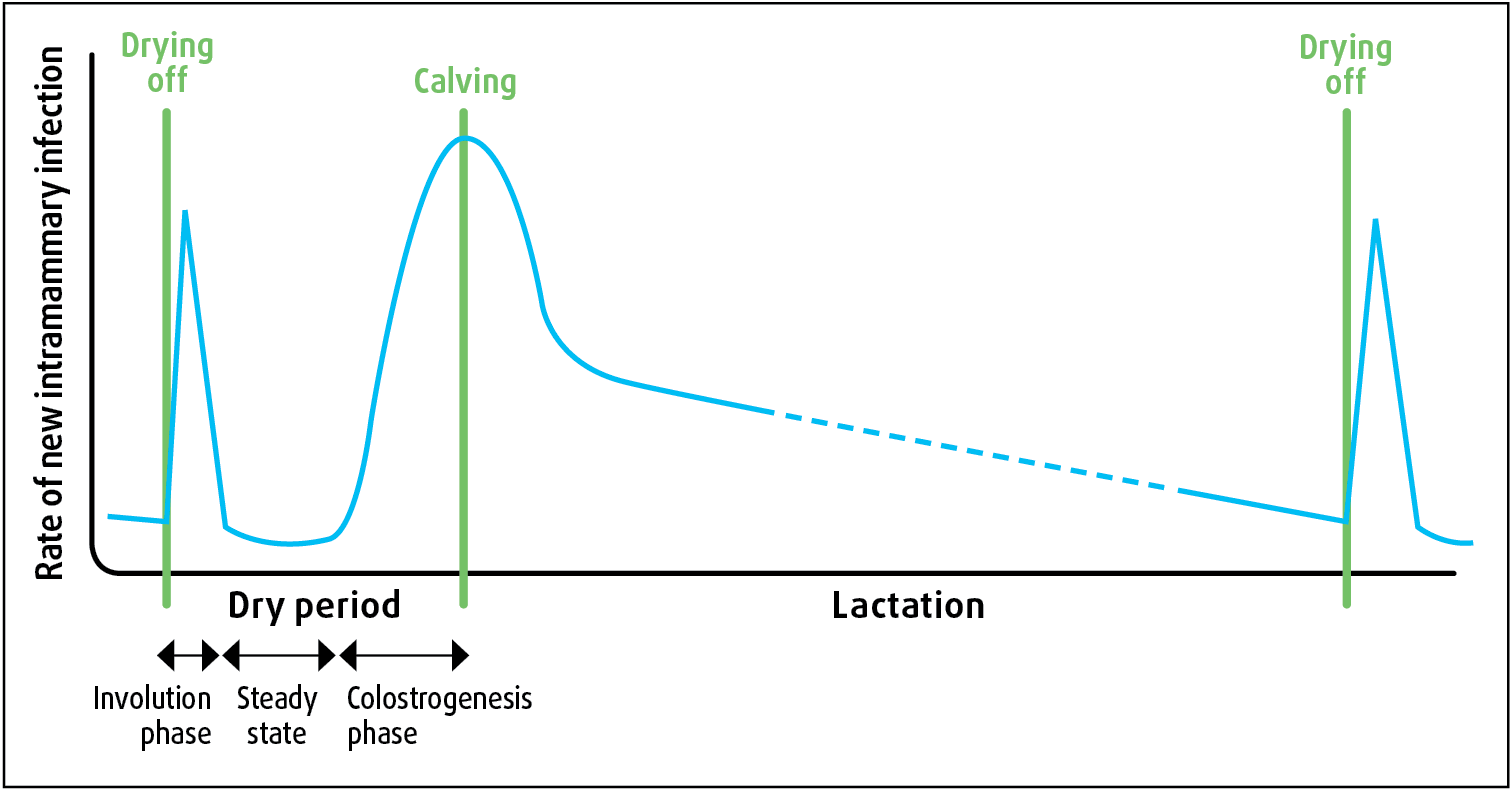

Figure 2 illustrates the incidence of new intramammary infection during the dry period and lactation. The peak new infection rate is immediately before and after calving, with a steady decline as lactation proceeds. However, an additional peak takes place immediately after drying off, when the udder is in an involution phase, before a steady state during the middle of the dry period, when the new infection rate is very low.

The involution phase is variable in length and different cows appear to have variable efficacy at producing an effective natural teat seal (keratin plug). Certain cows will, therefore, be at greater risk of new infection than others, and perhaps this is an interesting area for genetic selection.

Abrupt drying off is important to reduce the risk of new infection establishing immediately before the dry period. While most farmers accept this (some traditionalists continue the old habits of once-a-day or every-other-day milking), it can become very challenging for cows producing in excess of around 15L to 20L of milk a day. In well-managed, high-yielding herds with short calving intervals, it is not uncommon to have cows yielding up to 30L per day at drying off.

Common problems encountered with abrupt dry off are severe udder distention, discomfort and milk leakage, all of which can increase the risk of new infection. When wishing to practise selective dry cow therapy, the quandary is obvious.

A medicinal product containing active substance cabergoline, a potent dopamine receptor agonist on D2 receptors, led to the inhibition of prolactin and, consequently, to a reduction of milk production. The potential benefits of the product as an aid in abrupt drying off by reducing milk production were obvious: to reduce milk leakage at drying off, to reduce the risk of new intramammary infections during the dry period and to reduce discomfort.

As such, it was potentially an important new medicine, not only to improve animal welfare, but to help reduce the risk of mastitis, and further enable successful selective dry cow therapy. Unfortunately, the product was withdrawn from sale throughout Europe in June 2016 due to reports of adverse events (hypocalcaemia symptoms) in some cows, which may have been associated with it.

Meanwhile, abruptly drying off high-yielding cows remains a problem for many farmers, with no easy solution.

Due, at least in part, to our persuasive efforts as vets, by the 1980s blanket antibiotic dry cow therapy for mastitis control had become the norm in the UK, as in other countries. Now, however, it is time to march to the beat of a different drum.

Antibiotics used in dry cow therapy have two important, but distinctly different, functions: to eliminate infection present at drying off and to prevent new infection during the non-lactating period.

In the UK, internal, non-antibiotic teat sealants have been available in the UK for the past 15 years. Importantly, they have been demonstrated, under normal UK conditions, to be as effective as antibiotic dry cow therapy to prevent new dry period infections caused by major mastitis pathogens, particularly the environmental organisms (Huxley at al, 2002).

This means blanket antibiotic dry cow therapy is no longer justified, as it is possible to select those cows that do not have evidence of infection at drying off. In other words, selective antibiotic dry cow therapy can be adopted where every cow receives an internal teat sealant at drying off, but only those with evidence of infection receive additional antibiotic treatment.

It’s hardly a new development, perhaps, but selective dry cow therapy has been slow to gain traction. In part, this might be due to an “if it isn’t broken, why change it?” attitude. In part, it might be due to some initial poor experiences reported by farmers who used teat sealant alone, most probably due to poor infusion technique. Certainly, the use of sealant alone requires a careful, aseptic infusion technique to prevent infection of the udder at drying off.

Here lies an opportunity for vets, as selective dry cow therapy requires new herd protocols be set, staff training and ongoing monitoring of results. It certainly can be done very successfully, without any compromise to herd health (mastitis rates).

Success depends entirely on having the right selection criteria, good records and competent staff. An increasing number of dairy farms are leading the way on this, supported by their vets.

Some of the supermarket retailers and Arla, one of UK’s main milk buyers, are driving the agenda in this area, with a clear direction being set to move towards selective dry cow therapy for all farms. This is part of their strategies to reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in the dairy industry, which is important for the perception of milk and dairy production and the sustainability of their businesses.

Some farmers – and vets, too, dare I suggest – can be very slow to grasp this plain truth: the dairy industry is under scrutiny and to continue to win consumers’ trust and respect, we must take every opportunity to review our procedures and adopt best practice. Blanket antibiotic dry cow therapy is the one example where prophylactic antibiotic use is widespread in the dairy industry. A move to selective dry cow therapy is a clear opportunity to reduce overall antibiotic use and demonstrate the industry is responsive to its customers’ concerns.

After the steady involuted state, the colostrogenesis (transition) phase begins (Figure 2), and the mammary gland once again “wakes up” in preparation for milk synthesis.

Susceptibility to new infection increases as the keratin plug begins to break down, and the cow experiences both a natural leukopenia and a downgrading of leukocyte function, causing a dip in her innate immunity (Mallard et al, 1998). Colostrum leakage may occur, and it should be noted protective dry cow treatments, whether antibiotics or teat sealants, will no longer be offering protection at this point.

Given dry cows lie down for around 12 to 14 hours per day, and their teats will often be in contact with bedding with a very high pathogen load, it is perhaps not surprising the days either side of calving are very high risk for new infections to establish. Poorly ventilated, dirty and overcrowded accommodation will create the greatest risk. Loose housing (straw) has many benefits for housing calving cows, but mastitis control is not one of them.

Older cows, those suffering metabolic stress (for example, ketosis) or disease (for example, milk fever) and higher-yielding cows are more likely to have reduced immunity, and will be at particular risk.

The author advocates milking cows as soon as possible after calving (to reduce over-full udders) and immediately adopting twice-daily full milking to reduce the establishment of new infection.

However, it is very common practice for UK farmers to delay milking fresh-calved cows, or to practise once-daily milking and to only partially milk them out in the first few days. In part, this is for milk fever control (not recommended) and in part it is due to the common practice of leaving calves to suckle their dams. In addition, the author suspects, it is because farmers are sometimes wary of taking fresh-calved cows into the parlour in case they slip over and become recumbent, particularly where milk fever is poorly controlled.

These are understandable concerns and, in addition to instituting a proper milk fever prevention strategy, having a facility to machine-milk cows in the calving pen can be an excellent solution (Figure 3).

Vaccination may be used to boost acquired immunity and reduce the risk of clinical mastitis. The only licensed mastitis vaccine in the UK is Startvac (Hipra), which contains inactivated E coli (J5 antigen).

Evidence shows using vaccination can reduce the clinical severity of E coli infections in UK herds (Bradley et al, 2015), and vaccination appears to have a role to complement other mastitis control strategies. In practice, vaccination for mastitis is still uncommon in the UK, and the author suspects this is as much to do with farms’ ability and willingness to follow a vaccination programme as it has to do with vaccine cost.

Pegbovigrastim injection (Imrestor, Elanco) is another approach to immune modulation. It is a synthetic cytokine, mimicking the action of granulocyte colony stimulating factor, which stimulates the growth and differentiation of neutrophil precursor cells. The net effect is an increased number of neutrophils and an increase in their biological activity.

The recombinant molecule is attached to a water-soluble polymer (“PEGylated”) to increase its half life, and hence period of activity in the cow. This novel pharmacological approach of enhancing an integral part of an animal’s natural immune response is quite different to vaccination, which stimulates an acquired immunity. As mastitis immunity is very dependent on the innate cell-mediated immune response (Burton and Erskine, 2003), this has, arguably, hitherto limited the effectiveness of vaccination against many of the common pathogens.

It is claimed pegbovigrastim injection enhances a non-specific innate immune response, particularly in periparturient cows with an inherent immune suppression associated with normal hormonal changes, which occur around parturition.

The medicine is licensed for use in dairy cows around two weeks before and on the day of calving. While it is licensed to restore the function and increase the number of neutrophils, which fight a broad range of pathogens, it has a specific indication for reducing the risk of mastitis in the early lactation period.

Quite new to the UK market, it does have the potential to further reduce our need for antibiotics. Again, here lies a great opportunity for vets in practice to ensure their farm clients have the right information to base their decisions on. To understand the potential cost benefits of using the medicine, and to monitor results, robust data collection and analysis would be beneficial and vets are best placed to help their clients in this area.

Particularly because of their reduced immune function around calving, a key element of successfully protecting dry cows from mastitis infection is to ensure they are never overcrowded.

The obvious reason for this is to reduce the pathogen load, but crowding can also cause stress and can reduce feed intake. Preventing fat mobilisation and metabolic stress is important so further immunosuppression is not caused (O’Boyle et al, 2006).

Overcrowding can be with respect to feeding space, water space or lying space – and sometimes all three. Table 1 shows the minimum space allowances for Holstein cows in the dry period. Always look at all three aspects.

| Table 1. Space allowances for dry cow Holsteins | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Space per cow (minimum) | Notes |

| Feed space | 85cm | Or 5 head-lock spaces for 4 cows. Ensure all available space is being used and that feed is fresh at least daily. |

| Water space | 10cm | Or 1 rapid drinker per 100 cows. Always have more than 1 water point per group, and stress-free access is important, too. |

| Lying space (loose housed) | 1m2 per 1,000 litres of milk production | Plus a third as much again for loafing/feeding area. The devil is in the detail: good layout is needed to ensure the whole lying area is usable and hygiene is good. |

| Cubicles (width) | 140cm | At least one cubicle per cow, preferably deep sand bedded. |

| Adapted from Nordlund (2006) | ||

One of the most valuable things a vet can help his or her dairy clients with is calculating the maximum number of cows for any given shed or space, based on the most limiting factor (feed, water or lying space). Better still is if the farmer sticks to it (Figure 4).

Many dairy farmers expand their herd sizes on an almost-constant basis. Usually, more milking-cow accommodation is built and this is often followed by a parlour extension. Next, usually because calves are coming out of the farmer’s ears, new calf pens are constructed. Lastly, in the author’s experience, consideration is given to additional dry cow accommodation, and when it is addressed, the next wave of expansion has already occurred, so it is already over-stocked when a slight rise in seasonal calving numbers occurs.

For all-year calving herds, it is the convention to factor in a 30% to 40% seasonal variation in calving numbers. Therefore, the dry cow accommodation should be built for 130% to 140% of average requirement (Panel 1).

Herd size: 300 cows

Dry period: 8 weeks (5 + 3 weeks)

Calving interval: 400 days

In-calf (replacement) heifers housed with dry cows for past 8 weeks of gestation

Herd re-calve rate: 75%

Replacement rate: 25% (that is, constant herd size)

Expected number of calvings per year = 75 heifers (0.25 x 300) + 205 cows (0.75 x 300 x 400/365) = 280

Average calvings per week = 5.4 (280/52)

Average number of dry cows = 43 (5.4 x 8)

Total dry cow accommodation required = 60 spaces (43 x 1.4)

(For example, 37 far-off spaces plus 23 close-to spaces for a two-group 5:3 week system)

The premise is that if the accommodation is built for the average requirement, it will be overstocked for 50% of the time. Overstocking will always lead to problems, so this means the farm will experience post-calving difficulties for 50% of the year. This rings true for many farms in the UK.

Farm animal vets understand prevention is better than cure for bringing value to their clients. The additional recent increase in scrutiny over the use of antibiotics further promotes a preventive approach to herd health management.

It can sometimes be frustrating to be a farm vet; we understand what we should be doing, but are faced with farm clients looking for the “quick fix” once a problem is apparent.

In the face of a client’s increased mastitis rate, nothing is more frustrating than being asked for “a new tube, because my old one has stopped working”.

Having a few new tricks up our sleeves, whether they be new pharmacological developments or new approaches to dry cow management, can be useful in our endeavours to reduce mastitis, to keep cows more healthy and to promote more responsible use of medicines.