22 Aug 2023

David Charles CertHE(Biol), BVSc, CertAVP, PGCertVPS, MRCVS provides a comprehensive guide to multiple options and how vets can give opinions on different techniques.

The idea of manipulating the breeding season in sheep is not a new one, with both hormone impregnated intravaginal devices being reported as available pre-1960 and vasectomised rams well before that (Henderson, 1985).

As the role of the farm animal practitioner continues to evolve, it is important to remain abreast of newer products and options available to our clients, as well as to be in the best position to offer bespoke breeding advice to our sheep clients.

With the lamb price rising and being considered strong over the past few years, the author was able to successfully launch Midlands Advanced Breeding Services in 2021, which offered progressive services (such as laparoscopic AI) and also bespoke breeding plans and advice on manipulating the breeding season in flocks across the midlands.

Panels 1 and 2 outline commonly accepted benefits of advancing and synchronising ewes within a flock. Most notable is the fact that the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board market data shows clients could receive an average of 21% higher prices — p/kg based on the Standard Quality Quotation (SQQ; Forkes-Rees, 2022) – by selling lambs in April/May compared to July/August. In 2022, the average SQQ for April/May new season lamb was 658p/kg and for July/August it was 540p/kg (Forkes-Rees, 2022).

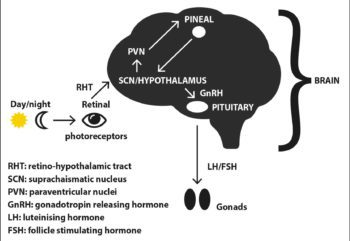

Sheep are seasonally polyoestrous and “short day breeders”, with their cyclicity being influenced by the time of year. In brief, this is because melatonin is only secreted from the pineal gland in darkness, while the hypothalamic sensitivity to melatonin (and, therefore, gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] release) is limited to the afternoon, therefore requiring short daylight hours for a correlation (Abecia et al, 2012; Figure 1).

The classical breeding season for sheep sees mating in the autumn/early winter to allow for spring lambing and optimal survival rates. Many clients will use the adage “in with a bang, out like a fool” to reference the fact that introducing the rams on Bonfire Night (5 November) should allow for lambing to begin on April Fool’s Day (1 April).

The typical reproductive cycle sees a 17-day oestrous cycle (which occasionally is 16 days) and oestrus behaviours being exhibited for 24 to 36 hours, with ovulation occurring 24 to 30 hours after the onset of oestrus (Menzies, 2018; Wright, 2021).

Therefore, manipulation of the breeding season can be achieved through the use of exogenous hormones – a summary of which is provided in Table 1.

Regarding progesterone or progestagen-releasing devices, two options in this category exist – a flugestone acetate (FA) impregnated intravaginal sponge and a progesterone (P) impregnated controlled internal drug-release device.

The principle with these devices is that while in situ, the P/FA mimics corpus luteum P4 activity and blocks the oestrogen-GnRH-LH positive feedback loop, allowing follicular development, but preventing the pre-ovulatory LH surge. On removal of the devices, a sudden and rapid drop in P/FA removes the block and allows GnRH pulsatile release, which in turn triggers pulsatile LH release from the anterior pituitary gland and the LH surge required to stimulate oestrus and ovulation.

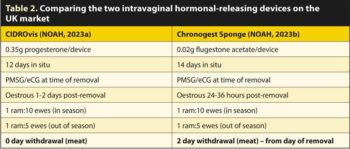

Most importantly, this happens in all ewes at the same time to provide synchronisation for a very tight service window – and, therefore, a tight lambing window. Particular adherence to the data sheet ratios (Table 2) is required to achieve the four to six-week advancement claims (NOAH, 2023a; 2023b).

The author’s preference is for the progesterone-releasing device on the market and finds that clients, colleagues and his own experiences correlate with the findings of Flesich et al (2012) and Swelum et al (2015) with regards to higher first service conception rates, improved fecundity, and a reduction in the mucopurulent and vaginal discharge on removal. Clients have also advised that they find the devices easier to use and that fewer “tails” of the devices are broken or devices lost in/out of situ.

Many farmers find that they need to insert these devices during the harvest season and, therefore, a commercial opportunity exists for practices to promote a VetTech administration service (with VetTech hourly rates typically being significantly lower than clinical vet hourly rate) as a cost-effective and time-sparing service for farmers to adhere to the required dates and timings on a protocol, while also not losing any time away from other seasonal necessities.

Table 2 shows some key comparisons between the protocols for P4 and FA options available to the UK market.

Pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) is a non-pituitary gonadotropin and an exogenous steroid hormone that acts on the ovary to stimulate follicular development and trigger superovulation. It achieves this through its follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH)-like activity and long half-life.

The number of follicles can be influenced by the dosage of PMSG administered and this must be taken into account, alongside breed fecundity, when calculating dosages. It is often likely that less PMSG can be administered the further into the normal breeding season (with the exception of if it is used for AI, where it is always recommended).

Users should note that a number of PMSG products exist (either on the UK market or available through a special import certificate); however, they are not all the same concentration. For that reason, clients should always be advised of the dosage in international units (IU) and millilitres so that the appropriate amount of IU can be given.

Farmers can do several things in advance of synchronisation and mating of their ewes to maximise conception rates (Panel 3).

Vasectomised rams are rams that are unable to impregnate fertile ewes; however, they retain their testicles and, therefore, their androgen production.

This point cannot be stressed enough as periodically clients will call in requesting a castration, but are actually desiring a vasectomy to produce a “teaser ram”. Obviously, castration cannot be reversed, so being entirely confident what clients want is critical and it is useful to educate reception or administrative staff who may book in the appointments regarding this difference.

The principle behind the “ram effect” or use of vasectomised males is that androgen-dependent pheromones are excreted by the vasectomised male, which – alongside the sight and smell of the males – stimulates the ewes’ pituitary glands to increase the frequency at which they release pulses of LH.

Provided that the anoestrus is not too deep in the ewes, increased LH pulsatility leads to follicular development and an LH surge. The LH surge stimulates ovulation, while also stimulating the theca and granulosa cells to develop into small and large luteal cells, which form the corpus luteum to release progesterone and maintain the pregnancy (Menzies, 2018; Kenyon et al, 2011).

The surgical approach uses an excision-ligation technique that is well described in the literature (Crilly et al, 2022; Hallowell and Potter, 2016) and, therefore, felt to be beyond the scope of this article.

The author promotes the use of knee pads if the surgery is done with the patient in a “tipped” position (Figure 2), with other alternatives being the use of turnover crates or laparoscopic AI cradles. The gold standard is to send the removed sections of cord for histological examination or to express sperm on to a slide for microscopy (Axiom, 2023; Crilly et al, 2022).

Clients will often ask their vet to advise them what the optimum timings and ratios are for use of vasectomised males. The author recommends a ratio of 1 vasectomised ram:50 breeding ewes with 1 entire breeding ram:20 breeding ewes afterwards. Some evidence exists in the literature that a level of “ram effect” can be observed with ratios as high as 1 vasectomised ram:150 breeding ewes; however, the concluding evidence showed that 1:50 was preferable (Kenyon et al, 2011).

The true “ram effect” will only be observed if ewes are separated from any males by sight, sound and smell, and a minimum of one mile for at least six weeks prior to introduction of the vasectomised males.

This can be challenging for clients with smallholdings, or lots of neighbours with sheep, and should be discussed with them before investment in the procedure. Considerations for various factors (as outlined in Table 3) in the rams selected for vasectomisation can increase the return on investment.

Ewes will ovulate within three days of introducing the vasectomised males that are removed after 14 to 16 days; (Crilly et al, 2022) found that ewes would have a second ovulation on days 18 to 20 post-introduction of the vasectomised males.

Therefore, changing from the vasectomised to the entire rams on day 16 means any early ovulating ewes will still be covered by the breeding rams at this ovulation.

One SC melatonin implant is available on the market. It requires an SC injection at the base of the ear and provides a dose of 18mg/ewe (NOAH, 2023c). When used as directed it stimulates early onset natural breeding activity by providing high dosages of melatonin before the natural onset, with it acting on the same pathways as observed in Figure 1.

Farm animal practitioners who do a lot of cattle work will be familiar with the use of prostaglandins to manipulate the breeding cycle in cattle. In sheep, their use is limited as they act on the corpus luteum. Therefore, they may have a role in synchronisation (within the breeding season); however, they have no ability to advance the breeding season and act on the ewe in anoestrus.

The author finds his use of prostaglandins of their analogues in sheep is solely limited to correcting cases of misalliance.

An increasing demand for laparoscopic AI of ewes has occurred over recent years in the UK. While it is an involved procedure and requires skilled operators who have undertaken further training and significant investment of equipment, the benefits for clients can be vast. Some of these are outlined in Panel 4.

With laparoscopic AI, the timings are critical and client adherence to any protocols regarding removal of intravaginal devices is paramount to the success of the programme.

Multiple methods for advancing or synchronising the breeding season in ewes exist and can be beneficial to flocks of all sizes and purposes.

By having a good vet-farmer relationship and developing their understanding of the clients’ needs and objectives, vets can provide a key opinion into the most appropriate techniques. Furthermore, by investing in new services and considering opportunities such as the use of VetTechs to apply progesterone/progestagen devices, additional income streams can be created for practices.

When advising clients on the options it is important to stress that in most scenarios the breeding rams will be working harder (especially if ewes are synchronised) and, therefore, must be fit for breeding purposes. The author heavily recommends rams undergo a pre-breeding examination as detailed by the Sheep Veterinary Society guidance documents (2014). This is perhaps even more important with a recent study (Price, 2021) finding more than 20% of rams were sub-fertile.

Whichever method the clients select, it is important to consider how you will present and signify the importance of the timings of any protocols.

One example, shown in Figure 4, provides clients with clear instructions and timings to maximise their success rates, by providing a clear, well-branded protocol sheet with the order that increased client compliance with protocols.

The client should also be clear on the required ram:ewe ratios.

In his previous practice, the author also built a calculator that would auto-populate the dates based on the user inputting either an intended mating or lambing date. This allowed all the staff to feel confident in advising clients on the timings without needing to calculate under pressure (Figure 5).