15 Oct 2018

Sophie Mahendran considers factors in maintaining fresh cow health, such as a low stress, comfort, feed access and monitoring. Includes video content.

Figure 1. A fresh cow drinking a rehydration oral fluid after a hard calving.

The success of a cow’s lactation is dependent on many factors. Careful preparation of the body is needed during the pre-calving period to ensure the cow is in the correct body condition with optimal macromineral status, followed by high levels of care and attention during the post-calving period to minimise the occurrence of adverse health events.

This entire time course is covered by the term “transition period”. This article will focus on the post-calving portion, with cows within this important 30-day period post-calving referred to as fresh cows.

Care of the fresh cow begins immediately post-calving. Many dairy units will have standard operating procedures in place to care for cattle in the periparturient period, with provision of liquid hydration, palatable food, pain relief and prompt milking.

Provision of these key aspects is often easier to initiate on larger units where dedicated staff may be employed to carry out these tasks promptly; however, similar levels of care can be achieved on smaller units through organisation and careful planning.

Cows are often thirsty post-calving, with provision of a bucket of warm water placed next to the calf usually encouraging them to drink. The addition of fresh cow supplements containing calcium and dextrose to the water can be used to rapidly provide energy and a calcium boost (Figure 1). This is important to maintain hydration and also to encourage food intake. If cattle are unwilling to drink – as may be the case following difficult calvings – oral drenching with around 20L of fluid using an Agger’s pump may be carried out (Figure 2).

The provision of pain relief to fresh cows may also be of some benefit. Some research has shown it may be inappropriate to give cattle NSAIDs pre-calving as this is linked to an increase in the likelihood of stillbirths (Newby et al, 2017). This same research has also indicated the use of NSAIDs within 24 hours of calving may increase the risk of cows developing retained placenta and, therefore, metritis. However, in the author’s opinion, if cattle have experienced a difficult calving (prolonged period of second stage labour, or fetal malposition with/without use of calving aid) or have visible vulva swelling or udder oedema, it is appropriate to provide analgesia to these cattle. Selection of cyclooxygenase-2-specific NSAIDs can reduce unwanted side effects, which may be linked to some of the outcomes recorded in the mentioned research. Trying to ensure fresh cows are as comfortable as possible post-calving will increase their feed intakes and reduce the associated negative energy balance implications.

Fresh dairy cows are often on a metabolic knife edge, with a gross mismatch between their energy intakes, and overall amino acid and glucose usage for milk production. This can be exacerbated by rapid changes in diet and poor rumen preparation for consumption of high starch diets when fresh cows move on to a milking cow ration.

It can take approximately three weeks for the rumen microflora to adapt to new diets, as well as the rumen papillae increasing their surface area to absorb the increased levels of volatile fatty acids being produced.

Approximately 30% of body condition score is lost in the first 10 days post-calving, with negative energy balance and the development of ketosis being associated with prolonged immunosuppressive effects, such as decreased acute phase protein production. The low intake of protein as a factor of low dry matter intake (DMI) may also result in low immunoglobulin production, with low levels of the amino acid glutamine being further linked to reduced immune function due to its role as an energy source for white blood cells. Ensuring fresh cattle have easy access to highly palatable feed will improve DMI and energy status, with provision of increased feed space for fresh cows (80cm to 100cm per cow) helping to minimise bullying and displacements.

Transitioning into the milking herd can be a very stressful time for fresh cows due to changes in social group, alterations in the housing environment and the process of being milked. The ideal scenario is the provision of a fresh cow group, consisting of a smaller number of cattle in a lower stocking density group, with excellent cow comfort and feed access. This will generally ensure fresh cattle will remain in a more familiar social group with the same animals they were transitioned with.

In addition to a fresh cow group, a heifer group is also advantageous, as these animals tend to be the lowest socially ranking, which results in increased standing times, reduced feed intakes and a general increase in stress levels. Parlour training of heifers prior to them calving and entering the herd can also be beneficial, as it allows familiarisation with the sights and sounds of a milking parlour (which are often very loud with very confined spaces), resulting in calmer heifers entering the parlour for their first milking postpartum.

Cow comfort is critical for fresh cows, with the time around calving being a risk period for the development of lameness due to the effects of calving-related hormones (relaxin and matrix metalloproteinases) potentially causing slackening of the suspensory apparatus and the sole soft tissues being at their thinnest around one week post-calving, which makes the corium vulnerable to damage (Newsome et al, 2017).

The most comfortable type of housing is a deep straw, loose housed yard. However, these can be very challenging to maintain a high level of hygiene in and, given the recent high costs of straw, are not generally practical as a housing type for milking cows. Deep, sand-bedded cubicles offer the highest level of comfort, while providing a relatively inert substrate that keeps environmental bacterial levels to a minimum. The least comfortable cubicle bed consists of mats – these offer very little cushioning or padding the cow, and often result in high levels of hock and knee bursitis. Comfort of mat-based cubicles can be enhanced by covering in a deep layer of additional bedding material, such as sawdust or recycled paper bedding.

Cow comfort can be quantitatively assessed by measuring the lying times of cattle using leg-based accelerometers or, more simply, by calculating a lying index for a group of housed animals (Figure 3). This is done by counting the number of cows lying in a cubicle, divided by the total number of cows touching a cubicle. The target is to have more than 85% of cattle that are in contact with a cubicle to actually be lying down in it. If the number is lower than this, an assessment of cubicle dimensions, lunge space and comfort of the bedding needs to be evaluated.

Fresh cows are at a high risk of developing disease due to the naturally occurring decrease in immune competence around parturition, which can be heightened by development of a negative energy balance and also the occurrence of hypocalcaemia (Lacasse et al, 2018). In addition to this, other common diseases of the fresh cow include ketosis, milk fever, mastitis, metritis, endometritis and a left displaced abomasum (LDA).

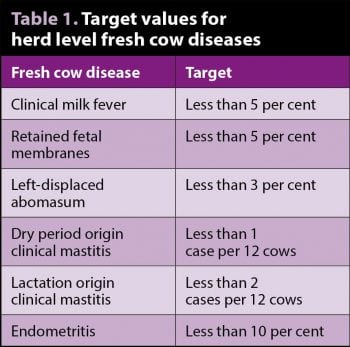

Recording these diseases is important – both to provide a baseline to indicate where improvements are needed, but also to allow the effects of any changes made to be monitored. Example targets for these diseases are given in Table 1 (Remnant et al, 2014).

The cost of these diseases can be substantial due to the loss in milk, drug costs, reduction in fertility and increased risk of culling. However, correct transitioning and care of the fresh cow into the herd can greatly reduce the risk of their occurrence. Hypocalcaemia is considered a gateway disease for many of these conditions due to its use in muscle contractions. This means having low ionised blood calcium levels can affect teat end sphincter closure for mastitis, abomasal contractility for LDA and slowed uterine involution, which prolongs a cow’s return to cyclicity.

Close monitoring of fresh cows to identify at-risk animals is very important – cows that had a short transition period, have Channel Island genetics or have a history of hypocalcaemia may all be candidates to receive prophylactic oral calcium boluses. Administration of oral calcium boluses to these high-risk cows can help prevent development of clinical hypocalcaemia and is easily done with appropriate handling facilities with minimal stress to the cow or farmer.

Maintaining the health of fresh cows requires appropriate facilities to provide a low stress environment with close observation by staff for signs of disease, high levels of comfort and easy access to feed. Each farm is different, but walking through the journey a fresh cow takes – from the calving yard to her movement into the herd – can help identify areas of concern, and the effect of focused improvements monitored through the collection of appropriate data on the farm.