17 Sept 2018

Philip Elkins, in the first of a two-part article, looks at methods to help achieve a successful outcome from this crucial period.

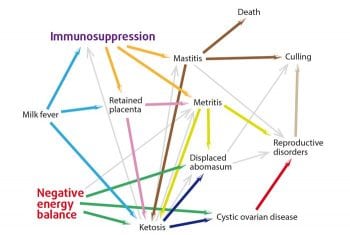

Figure 1. Interrelationships of transition cow diseases.

For many years, farmers and vets have been aware of the importance of calving in the risk cycle of a cow. In more recent times, however, the focus has not just been on calving, but the transition period too.

This involves metabolic and immune preparation for calving, and the following lactation – plus prepares the animal for the increase in demands associated with reaching peak milk production. Whether this period is referred to as 60 days, 90 days or any less, prescriptive time period is not important; what is important is to recognise the stages involved in the conversion of a pregnant, non-lactating primiparous – or a late lactation multiparous animal – to one successfully achieving peak milk production.

It is also imperative to understand the criteria on which the transition is deemed successful, such as a return to normal ovarian cycles and elimination of postpartum uterine infiltration. Understanding these stages enables a veterinary advisor to assess transition success, identify risk factors for transition failure and undertake steps to maximise the ability of cows to pass smoothly through this specific time. As any basic literature search will show, published studies on the transition period are numerous and wide ranging.

The purpose of this article is not to cover all research in depth, but to give the practitioner a suitable background with which to confidently assess transition success, implement monitoring strategies, initiate investigations into transition failure, and then be aware of the options available for increasing success. A logical approach is the first step to any process.

As defined previously, when considering the transition period, one must start with the process of the termination of lactation – drying off. At this stage, cows usually undergo a significant dietary modification associated with a change in nutritional requirements, and a change in social group and udder physiology.

It is widely accepted early involution presents a major risk period for the acquisition of new intramammary infections with environmental pathogens1, and the risk of impaired udder health is influenced by different management strategies2. Cows that develop clinical ketosis post-calving show changes in innate immunity and metabolism from eight weeks prior to calving3, with the dry period length having implications for future milk production, udder health and survival4 – hence, the timing of, and nutrition around, drying off is critical to success.

The dry period is often considered a relatively steady state in terms of metabolic and udder health challenges. However, strategies including split dry periods and non-optimised rations can have prolonged consequences – including post-calving disease3.

The pre-calving period carries significant disease risk5 associated with a reduction in the number and activity of neutrophils6. A number of diseases are associated with, and can be predicted by, failure to achieve suitable nutrition, calcium metabolism or immunity pre-calving7. Even in cows that do not show the classic clinical signs of hypocalcaemia including recumbency, blood calcium levels show reductions immediately after calving. This resolves over the following seven days as they respond to the change from low calcium requirements for maintenance and fetal bone mineralisation to that associated with milk production8.

Similarly, all cows undergo a period of insulin resistance, reduced feed intake, negative energy balance and weight loss post-calving, reduced immune function before and after calving, and bacterial contamination of the uterus immediately after calving9. Many of these conditions are a response to physiological adaptations to calving, but strategies can be put in place to reduce their severity and impact10. The physiological changes associated with initiating lactogenesis also provide a significant risk factor for the development of mammary gland infection11.

At post-calving, cows undergo further periods of metabolic and social stress. This time is associated with significant social changes, with cows often moving from dedicated maternity units to milking cow groups. Significant ration changes also occur – from one targeting dry matter intake and controlled energy supply to limit hepatic lipidosis and insulin resistance12, to one designed to provide the metabolisable energy and protein density required for peak milk production while minimising the long-term effects of depressed dry matter intake. It is easy to see how complex this process is when trying to describe it in a single sentence, and that is without considering the requirements for altered calcium metabolism and adaptation of rumen microflora to differing substrates.

As you can see, a lot of changes take place within a transition period, including at least two diet changes (more often three), at least three large social changes (although, in reality, social changes will be taking place more regularly as other cows are dried off or calve in), and major physiological changes involving the udder parenchyma, calcium homeostatic mechanisms and nutritional pathways.

Together, these present major risk of increases in stress hormones, altered metabolic pathways including fat metabolism and ketosis, and immune suppression through reduced numbers and functions of neutrophils. Together with the challenged physical barriers of the innate immune system, such as the teat sphincter and cervix, it is easy to see how this time period correlates to the highest risk of all manner of disease of an infectious and non-infectious nature.

As illustrated in Figure 1, many diseases are associated with the transition period, and complex relationships exist between those diseases. For a practitioner wishing to engage with a client around transition disease, this can be quite a daunting prospect. Equally, for a farmer concerned about milk fever rate – for example, initiating a discussion on reproductive disorder rate can be quite confusing.

The author’s advice when starting these discussions is two-fold: listen to your client and keep it simple. If a concern has arisen around the incidence of a certain transition cow disease, either from the farmer or from a practitioner, it would be foolish to ignore it. Concentrating an initial investigation on the primary complaint should help build the working relationship with the client and act as an opportunity to delve further into maximising the performance of transition cows.

The primary complaint may be mastitis in the first 30 days, milk fevers, ketosis cases, or something as vague as fresh cows just “not performing”. Once that primary concern is communicated, make this your first focus – it doesn’t stop you doing some legwork in the background to allow discussions to progress, but it will ensure the client is engaged from the outset.

Secondly, we know many of these conditions could be referred to as “iceberg” diseases, in that the overt clinical cases only represent a small proportion of the affected animals, and many of them are associated with higher levels of other diseases. We also know discussing improved recording of many separate disease entities, together with production figures, is likely to put many farmers off (although we all know it shouldn’t).

With this considered, the author is a big advocate of recording one simple parameter – transition success. It is much more engaging to record success than to record failure, but first we need to define success. The author’s definition is as follows.

A cow has successfully transitioned when she has reached 30 days in milk, having had none of the diseases in Table 1 and reached a suitable expected milk production level. The diseases in brackets require joined-up record keeping, together with an extended period of analysis, therefore can be included at the practitioner’s discretion.

Obviously, before undertaking any monitoring it is important to define those conditions being monitored. A “blue sky thinking” approach would allow the author to define each of them now for consistent recording; however, acknowledging the differences between the units we work on makes this impractical. For example, purulent vaginal disease could be diagnosed by routine vaginal mucus examination at 21 to 27 days post-calving using a standardised scoring method.

Farms on fortnightly or monthly routine fertility visits, or for those where diagnosis depends on the farmer noticing (and recording) a discharge while cows are in the cubicle shed, require different definitions. It is important these definitions are agreed with the farmer to be both achievable and accepted. Don’t forget to define target production levels at 30 days as these will vary massively between farms, and between primiparous and multiparous animals.

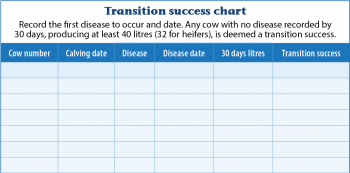

A strong, redeeming feature of recording transition success is the ease with which it can be carried out – irrespective of herd size. A simple chart can be designed in which cow number and calving date are entered, then any disease marks that animal as a transition failure. Run rates (extrapolations from specific time periods to an annualised figure) can then be calculated as frequently as numbers allow (be careful of over-interpreting small rate changes in small herds). For example, a herd calving 10 cows in a month, with 7 transitioning successfully, would have a 70% transition success rate. Figure 2 shows an example of a recording chart for transition success.

So what transition success rate should farms be targeting? Better than the current rate is the author’s answer – equally flippant as it is true. It is likely scope for improvement will exist on any farm. Due to the differences in definitions of disease – together with recording rates, which are notoriously variable – it is impossible to set targets that can be universally applied.

Accepted and published targets for many individual diseases exist, which will be covered in the second part of this article; however, due to the complex nature of disease interactions, none are published for transition success. Another approach is to ask the client what he or she deems an acceptable rate of transition success. In the author’s experience, more often than not, once success recording is implemented, few farms achieve what they deem to be an appropriate target. That is to say the levels of disease on their farms is higher than they would have previously anticipated.

Hopefully, this article has given a good recap of the stages through which a cow must transition before successfully entering a new lactation, as well as an overview of monitoring transition success.

Part two will cover how to investigate transition issues, including identifying risk factors and potential steps to increase success.