3 Jan 2020

Reproductive and respiratory diseases from autumn 2019 are the focus of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories’ latest update.

Image © jackmac34 / Pixabay

Presented are selected cases from the ruminant diagnostic caseload of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories.

Axiom provides a farm animal diagnostics service to more than 300 farm and mixed practices across the UK, and receives both clinical and pathological specimens as part of its caseload. The company is grateful to clients for the cases presented in this article.

The focus for this article is reproductive and respiratory disease in autumn 2019.

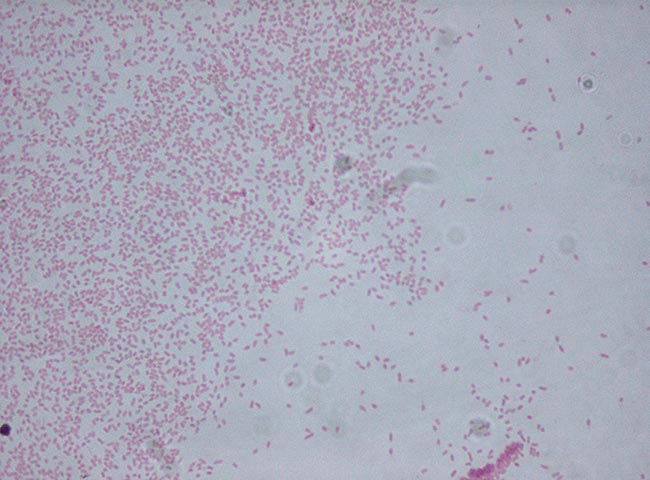

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Dublin was the cause of abortion in a number of herds.

In one case, Salmonella had been previously isolated on farm, with cows presenting off-colour and with mastitis.

In another herd, 15 of 18 aborting cows were seropositive for S enterica serovar Dublin; Salmonella had also been isolated from calves in this herd.

S enterica subspecies enterica serovar Montevideo was isolated from the stomach contents of an autolysed fetus aborted by a Holstein-Friesian cow at the beginning of the dry period. In Scotland, wild birds have been identified as a potential source of this serovar.

Streptococcus pluranimalium was considered the likely cause of abortion in a beef cow. This opportunist pathogen has been associated with a number of different conditions in domestic ruminants (and humans), including abortions.

A Leptospira microscopic agglutination test titre of 1/1,000 was detected in one of two south Devon cows that failed to conceive. Titres greater than 1/400 are considered consistent with recent exposure.

Among the less common isolates from mastitis cases were the environmental pathogens Aerococcus viridans, Pantoea agglomerans and Bacillus pumilus.

Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from two milk samples, including from a case of recurrent unresponsive mastitis in a Holstein-Friesian cow. Klebsiella species are environmental Gram-negative organisms and outbreaks of Klebsiella mastitis have been associated with sawdust bedding.

Serratia marcescens was isolated from a case of recurrent mastitis that failed to respond to amoxiclav; this may occasionally cause cases of environmental mastitis in cattle.

Enterococcus saccharolyticus was isolated from another milk sample, one of the more common Enterococcus species associated with environmental mastitis.

An extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, with extended resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics (penicillins and cephalosporins), was also isolated from one sample. These isolates are of potential public health concern.

Mycoplasma bovis was detected by PCR in a milk sample from three clinical cases of mastitis, in 9 of 15 milk samples from bought-in cows that had also seroconverted to M bovis, and in a bulk milk tank sample from a herd with non-specified chronic disease issues, the sample also being strongly seropositive to M bovis.

Candida krusei was isolated from two cases of mastitis. Yeast species often gain entry to the udder as a result of unhygienic intramammary infusion technique. Sometimes they may act as a true environmental pathogen when present in large numbers in the environment. Treatment with antimicrobials is ineffective.

Lungworm in cattle was diagnosed on several occasions using the Baermann technique, occasionally on histopathology and circumstantially by serology. Where clinical signs were reported, these included coughing, dyspnoea, tachypnoea and illthrift.

In one case involving a Jersey cow with a chronic cough and weight loss – in a herd with a severe outbreak of lungworm – histopathology of the lung detected severe bacterial bronchointerstitial pneumonia, with areas of lytic necrosis with eosinophilic coagula typical of virulent M bovis infection.

Evidence also existed of a significant eosinophilic component along with multifocal bronchiolitis fibrosa obliterans, both of which supported a concurrent or recent lungworm burden – and it was highly likely the lungworm infection had initiated the secondary bacterial pneumonia, including the mycoplasmal infection.

Lungworm in sheep was detected using the Baermann technique in a number of sheep flocks (Dictyocaulus filaria and Protostrongylus rufescens) and in a three-year-old male goat (Muellerius capillaris).

The latter can cause quite marked coughing and dyspnoea in goats. M capillaris and P rufescens require an intermediate host to complete their life cycle; a land snail in the case of P rufescens, and a number of different slugs and snails in M capillaris.

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) was confirmed with a rising titre on paired IBR glycoprotein E (gE) serology in one of four coughing adult dairy cows with pyrexia, increased cranioventral lung sounds and milk drop.

Three other cows in the herd had died in acute respiratory distress post-worming. The herd was vaccinated, but the bulk milk IBR gE serology titre was positive.

IBR was also demonstrated – on paired IBR gE serology – in one of a group of heifers that were IBR vaccinated, but had been showing respiratory signs and pyrexia (higher than 40°C) on joining the herd.

IBR was confirmed by PCR on swabs from animals in five herds. These included:

Active seroconversion to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was detected on paired serology in three dairy herds. It was also detected by PCR – along with a number of bacterial pathogens, including M bovis – in lung tissue from one of six recent calf deaths in a herd.

In a second case, RSV was detected by PCR in a lung sample from a two-week-old calf, one of a number of calves between three days and six weeks of age to die acutely. Evidence existed of cranioventral lung consolidation on postmortem examination (PME) and significant bronchiolar epithelial change – suggestive of pneumotropic viral infection – was seen on histopathology, with secondary bacterial pneumonia also evident.

Seroconversion on paired serology to IBR, RSV and parainfluenza 3 (PI3) was demonstrated in two of four two-month-old to five-month-old indoor heifer calves.

Ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma was confirmed on lung histopathology from an 18-month-old ewe in very poor condition and with respiratory difficulties that died within 24 hours of treatment.

The lungs were notably enlarged on PME. A mild overlying suppurative bronchopneumonia was also present.

Active seroconversion to M bovis was detected on paired serology in three herds with pneumonia outbreaks – one in two-month-old Holstein-Friesian calves, the other two in adult cattle.

Additionally to the aforementioned cases, M bovis was detected by PCR in a lung sample from a 15-month-old Aberdeen Angus bullock, with pleurisy on gross PME; and in a bronchoalveolar lavage sample from a 14-day-old calf.

Fulminating bacterial bronchopneumonia was detected in herds on a number of occasions by histopathology. Cases included:

In a third case – a dairy cow with blood and pus in the trachea, two-thirds lung consolidation and multifocal abscessation on PME – bacterial morphology on histopathology was suggestive of Trueperella pyogenes and Fusiformis species, which are common secondary pathogens in cattle and can be associated with previous viral and lungworm infection, and aspiration pneumonia.

In a fourth case – 1 of 14 preweaned dairy calves with pneumonia – histopathology of consolidated cranial lung lobes was more suggestive of haematogenous spread of infection, with a severe bacterial pleuritis extending into the lung parenchyma.

In a fifth case, more chronic bronchointerstitial pneumonia was seen on lung histopathology in an adult dairy cow and T pyogenes was isolated on culture; the animal had a severe tracheitis on PME, but changes consistent with IBR infection were not observed on histopathology.

Lung histopathology from an eight-week-old heifer calf detected two phases to the pneumonia present. The most significant was bronchointerstitial pneumonia with syncytia formation, most commonly associated with RSV or possibly PI3 infection.

A more chronic pneumonia was also present, with extensive areas of necrosis and fibrosis – most commonly associated with bacteria such as T pyogenes, Pasteurella multocida and, less frequently, M haemolytica and Histophilus somni. This had preceded the likely RSV/PI3 infection – raising the possibility of either a primary bacterial pneumonia or an earlier viral insult.

Bibersteinia trehalosi was isolated from the lung of a sheep that died acutely, consistent with systemic pasteurellosis, despite the animal being vaccinated with a multivalent clostridial and Pasteurella vaccine.

Septicaemic pasteurellosis was also diagnosed on lung and liver histopathology in one of two vaccinated sheep to die suddenly with no premonitory clinical signs. Evidence also existed of a severe bacterial bronchopneumonia and multifocal acute hepatitis with intralesional bacteria (“sawdust liver”). Additionally, the presence of bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia suggested pre-existing mycoplasmal infection may have predisposed the animal to the development of bacterial pneumonia

Similar cases were seen on lung histopathologies from two other flocks with lamb mortality, with underlying viral involvement and possibly Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae infection suspected, suggestive of atypical pneumonia.

In all three flocks, the affected sheep had been vaccinated against Pasteurella, but in at least one the course had only just been completed.

Atypical pneumonia is a multifactorial condition most frequently seen in post-weaned lambs presenting with illthrift and a mild cough, with a small number of cases developing a severe fulminating bacterial bronchopneumonia resulting in sudden death. It was diagnosed in a number of other flocks during the autumn.

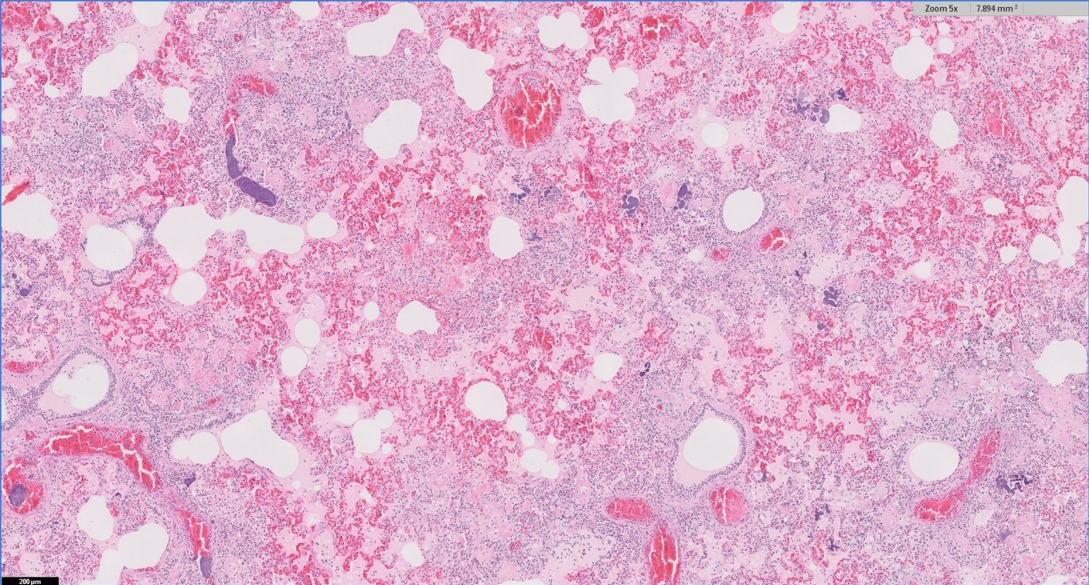

Pulmonary thromboembolism associated with spread of bacterial infection from a remote site was the cause of severe, chronic bronchopneumonia in a Holstein cow – one of a number of high-yielding cows to have spikes of pyrexia of unknown origin and signs of respiratory distress over several weeks.

RSV had been suspected, as rising titres had been seen on paired serology and very large bullae were seen on PME of this animal. However, in this case, no evidence of underlying viral involvement could be detected.

Liver abscessation secondary to ruminal acidosis is often the cause of pulmonary thromboembolism, but no evidence of this was found on PME and an alternative septic focus was, therefore, likely.

In a second case, a two-year-old Friesian heifer died suddenly, coughing up blood. On PME, multiple abscesses were found in the lungs and liver, and lung histopathology again had evidence of pulmonary vascular thrombosis, with associated necrosis, congestion and haemorrhage.