13 Aug 2018

Andrew Forbes discusses the current thinking and treatment and prevention options for liver and rumen fluke.

Had this article been written 10 years ago, the focus would have been fasciolosis resulting from infection with the liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica). However, over the past decade another trematode parasite, the rumen fluke (Calicophoron daubneyi), has appeared and is now common.

These two parasites share some common features, such as their intermediate host, the mud snail (Galba truncatula), the manifestation of infections, which can be acute clinical disease associated with the presence of high burdens of juvenile fluke in the liver (F hepatica) or duodenum (C daubneyi), or chronic infections associated with adult parasites in the bile ducts or in the reticulorumen.

A number of reviews of these two parasite species (Toolan et al, 2015; Williams, 2014) have been conducted, which the reader is referred to for general information.

This article focuses on some of the current issues facing farmers and their veterinary advisors in the control of fasciolosis and paramphistomosis.

Consistent, durable control of liver fluke in domestic ruminants is not easy for several reasons (Fairweather, 2011), including:

The reliance on flukicides in the control of fasciolosis places great pressure on understanding their properties and differences and ensuring use is appropriate in terms of timing and class of stock.

Using orally administered products containing triclabendazole has clear advantages, because (in the absence of resistance) their activity against the very earliest migratory stages of juvenile fluke in the liver means that:

Unfortunately, but inevitably, extensive use of triclabendazole has resulted in apparently quite widespread resistance (Kelley et al, 2016), which manifests in fluke of all ages. No immediately obvious and available alternative to TCBZ exists, but advantage has been taken of the synergy between certain combinations of flukicides (Fairweather and Boray, 1999). For example, in Australia products containing both clorsulon and nitroxynil are marketed and these provide efficacy against juvenile liver fluke that is comparable to TCBZ (Hutchinson et al, 2009). They are also effective against TCBZ-R isolates.

Surprisingly few published field studies are available to support the use of strategic treatments with flukicides. Strategic treatments have the aim of removing adult liver fluke – thus minimising liver fluke egg output in mid-summer (May to July) to reduce infection rates in snails, when their populations can expand rapidly – but they do not appear to be widely adopted (Over, 1982).

A report shows successful implementation of a strategic programme of treatments with triclabendazole on a mixed sheep and cattle farm; cattle were housed over the winter, but sheep were not (Parr and Gray, 2000). After an initial protocol of four treatments a year in both sheep and cattle to reduce the weight of infection on the farm, an annual programme of treating all cattle in April and November and all sheep in January, April and October/November was successful in reducing infection to a level where clinical fasciolosis was not seen (cattle were housed over the winter, sheep were not).

In the light of TCBZ-R, exclusive use of triclabendazole in strategic approaches to liver fluke control cannot be recommended now. To conserve sensitive isolates of F hepatica, a strong case can be made to restrict the use of TCBZ in cattle in an attempt to retain TCBZ for the treatment of acute fasciolosis in sheep. In sheep, too, at certain times of year – typically over winter when the majority of fluke present in the animal should be in the bile ducts – other flukicides can be used.

In cattle, one of the most common times to treat is at housing, but even here very few studies have been conducted to determine optimal use patterns; recommendations are commonly made on the basis of fluke biology and the properties of various types of flukicide. However, a comparative study showed that while some differences in efficacy among different flukicides were seen following treatment at housing, this was not reflected in animal performance (live weight gain), which was similar among all treatment groups, irrespective of flukicide (Forbes et al, 2015).

It should also be remembered that, based on health and safety, ease of handling cattle (Webster et al, 2008) and animal welfare, many farmers have a preference to administer formulations other than oral drenches, particularly in large cattle, although sheep farmers/shepherds generally prefer oral drenches.

In the UK and Ireland, reports of paramphistomosis appeared in 2008 (Foster et al, 2008; Murphy et al, 2008) and acute disease resulting from infections with immature conical fluke in both sheep and cattle were subsequently reported (Mason et al, 2012; Millar et al, 2012).

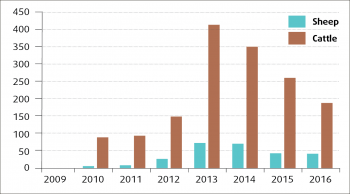

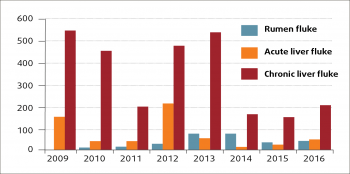

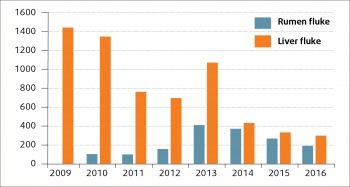

Since the initial appearance, the annual number of rumen fluke diagnoses reported through the Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis (APHA, 2016) has increased in both sheep and cattle, but especially the latter (Figure 1). Although considerable year-to-year variation in the number of liver fluke diagnoses (probably driven by weather patterns) can be seen, the number of liver fluke submissions in the past few years seems to have fallen in sheep (Figure 2) and cattle (Figure 3).

Initially, the species of rumen fluke involved in this increase in prevalence was not known, but DNA sequencing revealed its identity to be C daubneyi, formerly called Paramphistomum daubneyi (Gordon et al, 2013), and it appears this is currently by far the most common species found in domestic ruminants in the UK and Ireland. This species utilises G truncatula as its intermediate host, so inevitable epidemiological overlap between liver and rumen fluke can be seen.

The overall prevalence of C daubneyi appears currently to be higher in cattle than sheep. Infection with C daubneyi can produce a severe and potentially fatal disease in both young cattle and sheep when they are exposed to high levels of metacercarial challenge on pasture.

The juvenile fluke develop in the duodenal mucosa, where they can cause acute inflammatory changes and associated pathology (Anon, 2016a, 2017; Mason et al, 2012; Millar et al, 2012). Most cases, however, involve infections with adult fluke, diagnosed through faecal egg counts (FEC) or the presence of parasites in the reticulorumen at postmortem.

Adult rumen fluke infections are considered to be largely benign, but several anecdotal reports from the field of oxyclozanide-responsive ill-thrift in cattle show they are free of liver fluke (Foster et al, 2008; Murphy et al, 2008).

No licensed treatments for rumen fluke are available in the UK or Ireland, but oxyclozanide has been shown to be effective against both juvenile and adult C daubneyi (Alzieu et al, 1999; Arias et al, 2013; Paraud et al, 2009). The dose rate recommended for liver fluke is 10mg oxyclozanide/kg in cattle and 15 mg/kg in sheep, with no increase in dose at bodyweights of 350kg or greater (NOAH, 2015). However, against adult or immature rumen fluke, a number of different dosages (10mg/kg to 20mg/kg) and regimes (single or repeat treatment three days later) have been reported.

Given that both rumen and liver fluke share the same intermediate and final hosts, co-infections in either host can occur, and the consequences of this could potentially range from negative through neutral to positive interactions.

Evidence from studies in G truncatula shows negative interactions insofar as dual infections are uncommon in the field, probably because they are detrimental and potentially fatal to the snail (Rondelaud et al, 2007). A recent investigation into an outbreak of acute paramphistomosis in Ireland revealed that C daubneyi was dominant in both snails and metacercariae, with only one snail infected with F hepatica (O’Shaughnessy et al, 2017), suggesting rumen fluke may have displaced liver fluke in the snail population at that location.

Co-infections in the final host do occur – in an abattoir study, 47% of cattle with adult rumen fluke were also infected with liver fluke or had liver pathology (Bellet et al, 2016); 53%, therefore, were only infected with a single trematode species. Whether negative associations can be seen between rumen and liver fluke within the final host is a matter of speculation, although it can be hypothesised that duodenal pathology (Figure 4), induced by juvenile C daubneyi, could interfere with:

A recent, as yet unpublished, study at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Glasgow, showed a significant negative association between the presence of rumen and liver fluke eggs in faecal samples (p-value <0.0001), which provides some support for a negative interaction between the two parasites in the final host.

Abundant evidence shows C daubneyi is a common parasite in sheep and cattle in the UK and Ireland, and may, in time, become as, or more, prevalent as liver fluke. This leads to the intriguing possibility rumen fluke could replace liver fluke on farms where both intermediate and final hosts are present, thus reducing the risk of fasciolosis (O’Shaughnessy et al, 2017).

As acute paramphistomosis is uncommon and requires a high pasture challenge with metacercariae and as infections with adult rumen fluke are largely benign, the impact of trematode infections could be reduced if F hepatica populations decline as a result of a predominance of C daubneyi.

Acute fasciolosis in sheep and chronic infections in both sheep and cattle remain among the most important helminth infections of domestic ruminants (Forbes, 2017; Rojo-Vazquez et al, 2012) and it is premature to assume liver fluke will pose less of a threat if it is displaced by rumen fluke. Nonetheless, this is a plausible scenario.

Of course, it is also possible that as rumen fluke infections become even more common, acute paramphistomosis could pose a greater threat. The apparent negative effects of C daubneyi on F hepatica also beg the question as to whether cattle or sheep with adult rumen fluke should be (routinely) treated with oxyclozanide, given that C daubneyi can help in the control of liver fluke, which is pathogenic both in its juvenile and adult stages.