15 Aug 2023

Drawing on his own experiences, PHIL ELKINS BVM&S, CertAVP (Cattle), MRCVS provides a guide for new vets on tough call-out preparation.

As a new cohort of members of the royal college is sworn in, joining this amazing profession, it is worth looking at some of the challenges they will face over the next few years.

One of those is the emergency call-out to farm animals. While new graduates may not be on the out-of-hours rota by themselves initially, it is worth remembering emergencies do not only happen after 5pm, and that – even with the best planning, mentoring and structured responsibility – a time will come when less experienced vets will have to deal with their first emergency by themselves (or with an experienced colleague following some time behind).

In this article, the author will cover some thoughts regarding farm animal emergencies, learned through 15 years of clinical practice, mentoring new graduates, and providing training to structured graduate programmes on the subject.

Hopefully, these thoughts can help reduce the risk of a bad situation turning into a disaster. This article is based on personal experience, and rarely supported by published evidence.

Without a shadow of a doubt, the most common farm animal emergency is, and likely will be for a long time, dystocia. Despite advances in management and breeding decisions, a high rate of vet-assisted calvings and lambings still occurs, in particular with certain anecdotal patterns to distribution:

Following dystocia, individual sick animals and recumbency, followed by injuries, would represent the vast majority of farm animal emergencies. Occasionally, group level issues occur, and often represent the biggest challenge. This article is going to concentrate primarily on dystocia, but the principles transfer to all farm animal emergencies.

Many maxims in management speak exist for the most important tip with regards to all emergencies, but they are particularly relevant to dystocia:

And the author’s favourite:

Preparation takes time and commitment. Putting this effort in well in advance of the need will make positive outcomes more likely.

This may sound self-explanatory, but it really is essential to approaching dystocia. It is not uncommon to get called out by less-experienced stockmen to animals in first-stage labour, and understanding that, in many cases, these animals need nothing more than time. Equally, understanding the natural progression of parturition allows interventions to take place at appropriate times. The author’s indicators of relative urgency, based on this understanding, are:

All of these indicate a potential issue for normal parturition – either a lack of progress, cessation of stage-two labour, or foetal distress, and require urgent attention.

Although it is often emphasised during veterinary training, the taking of an appropriate history may seem superfluous for a dystocia – surely, if the client has rung for assistance, the focus should be getting there as quickly as is safe?

In many circumstances, this would be true. However, situations where, especially for the less-experienced clinician, an appropriate history can lead to a number of different actions, including – but not limited to – preparing a colleague for assistance, telephone advice to the client and discussing a set of circumstances with a colleague en route to the visit.

Consider the following scenarios. It is possible to successfully talk even the least-experienced farmer through a vaginal examination that will allow the clinician to determine the best course of action for the cow and calf.

Of course, if the client is not comfortable with this, visiting and examining the animal yourself is a viable option, but proceeding to calve the cow in early first-stage labour, rather than allowing time for soft tissue dilation and natural progression, may lead to more damage for the cow.

In both of these scenarios, taking a brief, but appropriate, history has allowed better preparation, and as a result, better outcomes for cows, vets, clients and practice. Both scenarios are based on the author’s experience as a recent graduate.

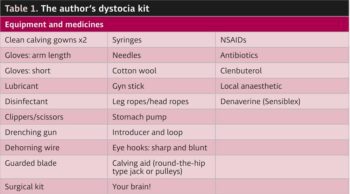

With farm animal emergencies, it is important to plan for every likely eventuality. Again, this may seem rudimentary, but little irks clients quite like vets having to return to the surgery to collect something, or the client having to make a special journey to collect medicines they would expect you to carry for aftercare. The author’s dystocia kit list can be seen in Table 1.

Ensuring the items in Table 1 are in your vehicle at all times means you are likely prepared for most dystocias. A drenching gun can be extremely useful for applying lubricant to difficult-to-access areas. A pump can be used in cases of rotten calves to apply gentle lavage to the uterus. A gyn stick is a length of food-grade plastic designed to assist with correcting uterine torsions or other malpresentations.

With dystocias, the temptation for farmers and vets alike is to grab something and pull. For farmers, this is often a case of continuing to do the same thing and hoping for a different outcome. Once the decision has been made to call the vet for assistance, the best approach for farmers is often to find something else to do until you arrive.

Communicating this in the right way can prevent you arriving to a situation that is far worse. Similarly, for vets, taking your time with the initial assessment will often lead to better actions. Use a clean, gloved hand and plenty of lubricant to assess the situation – count limbs, follow them all to a body and ensure you are aware whether they are front or back limbs. Take a few minutes to come up with a logical plan of approach, and some end points: if you have not achieved certain landmarks within a set time, it is time to consider changing your plan.

Some reliable indicators for success with cattle also can be adapted for sheep. If these points are not achieved with minimal tension, vaginal delivery without significant consequences for cow or calf is unlikely and an alternative route (caesarean, fetotomy or euthanasia) should be considered.

Some situations occur where easy delivery is not achieved despite achieving these landmarks: an underdeveloped or undilated vulva (episiotomy or caesarean), ‘water belly’ (fetotomy) and hip-locked calves (fetotomy).

With regards to caesarean surgeries, better outcomes are achieved when a decision to undertake surgery is taken early. In the absence of smooth, early progress, a decision to undertake a caesarean is rarely a bad one.

Take every opportunity to experience all stages of dystocias. It is only through involvement that you can get a true understanding of the range of “normal”. This extends to sick animals – by doing a full clinical exam on all sick cows, you will not only perceive all symptoms, you will also experience more “normal” symptoms.

With regards to dystocias, this, in particular, extends to the use of head ropes. A head rope will make parturition easier anyway, by bringing the rapid dilation needed by the nose to a narrower part of the legs, therefore decreasing the space required. However, most parturitions by definition do not need a head rope to progress. By placing a head rope at every occasion, it ensures that, when a head rope is needed, the manual dexterity and muscle memory needed to make this sometimes-awkward task routine is present.

So, in summary, for all farm animal emergencies, but particular with regards to the most common, dystocia, these steps will help increase the chances of a successful outcome: