6 May 2022

Nick Bell MA, VetMB, PhD, PGCertVetEd, FHEA, DipECAWBM(AWSEL), MRCVS discusses a significant problem facing the dairy sector across the world.

Figure 1a. Acute M1 lesions.

Lameness is a significant problem facing the dairy industry worldwide, having a major impact on cattle welfare and leading to substantial economic losses from reduced milk yield1 and infertility2. Digital dermatitis (DD) is one of the most common causes of lameness in dairy cattle3, and studies have shown that the prevalence of DD in dairy cattle can exceed 30%4,5,6.

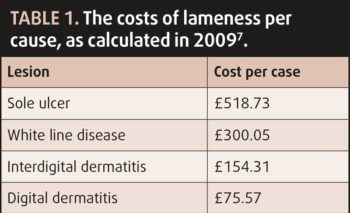

Economically, the costs of treating lameness are significantly outweighed by losses caused by a decline in production7. Reduced reproductive performance was responsible for 39% of the total costs, with decreased milk yield and increased culling contributing to 24% each; the cost of an “average” case of lameness was calculated to be £323.477.

DD is a highly infectious polymicrobial infection, with a complex, multifactorial aetiology of spirochetes from three families of Treponema species being commonly isolated8-10. Initially, early colonisers (for example, Gram-positive cocci, Campylobacter, Bacteroides and Fusobacterium) have been shown to change the environment of the skin from an aerobic to a more anaerobic one10, allowing treponemes to invade the skin through hair follicles and sebaceous glands11 or through wounds10.

Treponemes appear, over time, to encyst deep in the interdigital space, supporting the theory that they have mechanisms to facilitate recurrent infections deep in bovine skin, leading to the persistent, chronic and recurrent nature of DD12.

Typical DD lesions range from a superficial, circumscribed erosive type to deep dermal ulcers to dyskeratotic/hyperkeratotic growths, and deeply inflamed “proliferative” mixed skin lesions.

The M-score13,14 is commonly used to assess lesion progress, with M1 and M2 representing active lesions, M3 healing lesions, M4 chronic hyperkeratotic lesions and M4.1 reactivating hyperkeratotic lesions. Following infection, the condition will progress from small (less than 2cm) and active M1 lesions to the larger and ulcerated M2 type.

From this point, lesion progression can vary between the healing, the chronic and the reactivating stages, depending on type and speed of treatment offered. Prompt and effective treatment of M1/M2 lesions can reduce progression to the chronic and reactivating stages.

Infected lesions represent the major reservoir of infection, particularly the reactivation of M4 lesions. The slurry “foot-print” and fomites are considered key routes of transmission.

Under ideal induction conditions, lesions can develop within 21 days of infection10,15, but the average time from initial skin pathology to clinical lesion has been reported as 133 days10, allowing time for the prevention of new DD lesions forming in infected cattle by employing strict hygiene, foot disinfection and regular monitoring. Reactivation of chronically infected cows can happen over a much shorter time period, commonly within two weeks16.

Early detection and the targeted treatment of affected cows are key elements of control, along with environmental management (clean and dry feet), biocontainment (preventing spread to youngstock), biosecurity measures (closed herd) and disinfection protocols (daily foot bathing and disinfection of equipment used to examine, trim or treat the feet of cattle).

Early detection and treatment can deliver improved success rates, leading to enhanced welfare and production. The early treatment of acute DD lesions (M1 and M2) will have improved cure rates versus chronic lesions (M4/M4.1) where it is likely that the condition will be recurrent, despite treatment (Figure 1). As the major reservoirs of infection are DD foot lesions, it may be advisable to treat all lesions at the same time, regardless of severity or M-score.

Unless cows are out at clean pasture, DD lesions are usually covered in slurry, bedding material or mud, together with scabs, fibrin and exudates. Thorough cleaning, debriding and drying of the affected area is important for visualisation and to allow topical treatments to properly contact and penetrate the lesion.

Treponemes are sensitive to a range of antimicrobials17 and topical antibiotic spray is a good option in early DD lesions, following cleaning, debriding and drying. Standard oxytetracycline (OTC) spray contains approximately 200mg of active ingredient per application, exceeding the MIC for treponemes at the wound surface. This protocol appears more effective than the use of systemic antibiotics18.

The hyperkeratotic and necrotic nature of most lesions means injectable antibiotics are unlikely to penetrate lesions sufficiently well. Given targeted topical treatments appear more efficacious and carry less risk of resistance selection pressure, topical treatment represents the most responsible use of antibiotic for this condition.

In the days following treatment, foot bathing using an appropriately diluted disinfectant is likely to be beneficial for healing. No evidence is available to show that the off-licence use of antibiotic powders in footbaths has any advantage over other biocides. Indeed, responsible and ethical considerations on antimicrobial use mean use of antibiotic footbaths cannot be justified except for some very specific circumstance where they are needed on welfare grounds19.

Given that DD is a painful condition, the use of NSAIDs, alongside topical treatment, can be justified on welfare grounds. Surveys have reported that 9 out of 12 experts would recommend the use of NSAIDs for the treatment of active DD, but would reserve them only for cows with a mobility score of 320 – raising the question “why not also use in those cows with a mobility score of 2?”

A study (2021)21 explored the potential welfare and production benefits of using an NSAID (ketoprofen) to treat cows suffering from active DD lesions. A total of 158 cows with active DD lesions (score M1, M2 and M4.1) were enrolled and split into two groups (treatment and control). Each cow was mobility scored and assessed as lame if it had a score of two or three. Their stage of lactation and daily milk yield was recorded. At the start of the trial, the DD lesions present in both groups were cleaned, dried and treated with an over-the-counter (OTC) antibacterial spray. The treatment group then received a single IM injection of ketoprofen 100mg/ml. Both groups were assessed one week after treatment for their lameness score and milk yield.

Data analysed from cows that were lame at enrolment showed those receiving ketoprofen, at the first evaluation, were 20.2 times less likely to be lame at the second evaluation than those only receiving a topical OTC spray (p=0.027).

During the study, milk yield was assessed across a range of lactation periods21. Cows in the treatment group produced 3kg/day more milk than those in the control group for the week following enrolment. When data was considered only from freshly calved cows that were lame at enrolment, there was a significant benefit in milk yield of 10.5kg/day if they were given ketoprofen compared to the control animals (p < 0.05)21.

DD is a complex condition that can cause long-term cattle welfare and production challenges, although controlling it can be relatively simple. The chronic and recurrent nature of the disease means strict adherence to straight-forward foot hygiene protocols will control the disease, but the potential for frequent breakdowns can lead to frustration and stress for farmers.

A systematic approach to early detection, rapid and thorough treatment alongside disciplined prevention protocols should reduce the level of DD lesions, particularly in heifers and eventually in the whole herd as chronically infected animals are culled. The addition of NSAIDs (ketoprofen) to the treatment of active DD lesions can be beneficial for animal welfare and productivity.