18 Apr 2017

Sara Pedersen runs through full treatment options and prevention strategies – and outlines best foot-bathing practices.

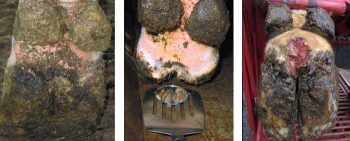

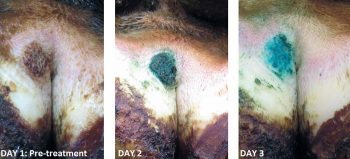

Figure 3. Response of a mild active lesion to treatment with topical oxytetracycline spray. Daily treatment for two consecutive days required. IMAGES: Farm Dynamics.

Most UK farms will have digital dermatitis (DD) present, and tackling it requires an integrated approach and a commitment to ensuring all aspects of it are carried out effectively and thoroughly. DD is best identified when cows are in the milking parlour and each foot can be individually inspected. Cases should be treated individually, although an outbreak will necessitate a “blitz treat” approach for all cows with active lesions. The author runs through full treatment options and prevention strategies – and outlines best foot-bathing practices.

Digital dermatitis (DD) is estimated to be present on more than 95% of UK farms and is often an ongoing grumbling issue, leading to decreased herd performance through reduced yields, poorer fertility (Argáez-RodrÍguez et al, 1997) and an increased susceptibility to other causes of lameness due to changes in hoof conformation (Gomez et al, 2015).

Tackling DD needs an integrated approach and, while on many farms several components of the integrated control plan will be in place, they are often not carried out effectively or thoroughly enough to gain long-term control.

It is often thought DD exists in only its active red, ulcerative form. However, it has many different stages that the infection cycles through, and many ways of identifying and categorising the different lesions have been suggested, although the most commonly used are the “M stages” (Döpfer et al, 1997; Berry et al, 2012; Panel 1).

Due to the invasive nature of the Treponema species that cause DD, they don’t just colonise the surface of the skin, but burrow deeper down into the dermis, encysting and creating a “carrier” state (M4; dormant lesion; Figure 1). It is these cows that are the main reservoir of infection in the herd.

The key to bringing DD under control once and for all is to firstly treat active (M2) cases and ensure they either return to uninfected (M0) or go through the healing process (M3) successfully to reach the dormant stage (M4), so effective measures can be put in place to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Early detection and prompt effective treatment is essential for all causes of lameness. However, not all cows with DD are lame, therefore mobility scoring alone isn’t an effective method of identifying all cows with it.

M0: Healthy skin with no evidence of previous lesion.

M1: A small, focal active red/grey circumscribed lesion less than 2cm wide with 1mm red foci.

M2: A painful large, ulcerative red/grey active lesion more than 2cm wide.

M3: A healing, painless brown scab typically seen after treatment.

M4: A chronic stage presenting as dyskeratosis or irregular proliferative hyperkeratotic overgrowths.

M4.1: A chronic stage with active, painful M1 focus.

Döpfer et al, 1997; Berry et al, 2012.

Research has shown the length of time taken from when treponemes first start to erode the outer skin layers to forming a red, active lesion resulting in lameness is, on average, 133 days (Krull et al, 2016). Therefore, a large window of opportunity is often missed if clinical signs of lameness are the sole method of detection.

Instead, to identify DD, feet must be inspected individually. The easiest way to do this is when cows are in the parlour during milking. Feet must first be washed to improve visualisation. Identification of early lesions can be aided by use of a mirror on a fish slice and a torch.

For dry cows, youngstock or robotic herds, this can be carried out at the feed barrier, but is hindered if the feet are dirty, so extra caution needs to be taken when deciding if a cow needs further inspection (Figure 2).

Cases of DD should be treated at an individual, rather than herd, level. In the face of an outbreak, or where DD levels are consistently high in a herd, the key to quickly gaining control of the infection level is to “blitz treat” all cows with any sign of an active lesion (M1, M2, M4.1).

Since the infected cow itself is the main risk to other cows, treating all infected cattle at once results in a rapid reduction in infection pressure since the treponemes only survive in slurry for a relatively short period (less than 24 hours at 17°C; Carter, personal communication).

The aims of treatment are for a quick resolution of the active lesion while minimising pain to the cow, using antimicrobials responsibly and reducing the risk of further encysting bacteria. Due to the way treponemes encyst in the skin, a true bacteriological cure is unachievable in the majority of cases, and so the aim is to resolve the secondary infection that develops on the skin surface – thus resolving the animal’s pain and also reducing shedding into the environment.

Topical therapies remain the most common method of treatment, although systemic treatments have been trialled to determine if a true bacteriological cure can be reached. Evidence remains ambiguous as to the benefits of systemic treatment (Laven and Logue, 2006) and, if compared to the treatment of treponeme infections in humans (syphilis and yaws), it is likely a true bacteriological cure will only be achieved through very high antimicrobial doses for a prolonged period (Evans et al, 2016).

The only licensed systemic antimicrobial in the UK is cefquinome. As it is a fourth generation cephalosporin – and, therefore, a critically important antibiotic – while licensed, it has to be considered whether its use in the treatment of DD can be considered responsible.

Antibiotic foot baths have often been the mainstay of DD control on many farms and still continue to be used. However, the increasing drive to reduce antimicrobial use – and also consider more responsible use – means they cannot be justified as part of routine treatment/control protocols. Aside from the fact the antimicrobial products commonly used in foot baths are not licensed – and, therefore, carry a seven-day milk withhold – they fall under the category of prophylactic use.

1: Lift affected foot in crush.

2: Wash lesion (including interdigital space) with clean water.

3: Dry lesion gently (do not aggravate) using swabs or similar (cotton wool not recommended as it sticks to the lesion).

4: Thoroughly spray with licensed topical antibiotic.

5: Leave to dry for 30 seconds.

6: Spray again and lower foot.

7: Return to clean, dry yard.

8: Record cow as treated and visibly mark to ensure follow-up treatments.

A reported tool for assessing antimicrobial use on farm demonstrated the use of a monthly antibiotic foot bath would add 25mg/kg (mg of antibiotic used per kg of livestock) to a farm’s usage over a year – the overall target per farm is less than 50mg/kg. Therefore, foot bathing alone would account for half of the target usage (Hyde et al, 2017).

It has been common practice to use bandages in the treatment of DD – either to hold a product on to the lesion, or to keep the foot clean. The disadvantages of using a bandage are plentiful and include cost, hassle/time taken to remove, risk of tendon injury if not removed, ability to create the ideal environment for DD to thrive once the product is no longer active, risk of chemical burn if the cow is passing through a caustic foot bath, and the inability to see the lesion and reassess it.

However, despite these disadvantages and their widespread use, a comparative trial has shown no benefit to bandages when it comes to a successful outcome (Cutler et al, 2013).

Perhaps a greater consideration is not what the bandage achieves, but why it is being used? If using bandages then it is also important to consider what it is holding on the lesion. Licensed treatments for DD are in the form of aerosol sprays and, therefore, do not require bandaging, which also allows for repeated treatments.

While products such as copper sulphate or zinc sulphate pastes have commonly been used in the past, these are no longer recommended, as not only are they painful for the cow and can be damaging to the raw skin, but they are also caustic and it is thought they can encourage the bacteria to go deeper into the skin and encyst, creating a chronic carrier state (Döpfer, personal communication).

While many products are used off-label for DD, such as tylosin phosphate, erythromycin or lincomycin hydrochloride powder, none are licensed for this use in cattle and carry a statutory seven-day milk withhold.

Given the research by Cramer and Johnston (2015) demonstrated application of antibiotic powder to DD lesions resulted in both contamination of the teats and also the milk with antibiotics, this off-label use should be strongly discouraged. Off-label antibiotics are often reached for when the alternative is not deemed to be successful – in this case, licensed topical antibiotic sprays that carry no milk withhold and do not put the producer’s milk contract at risk.

It is the author’s experience that in most cases where these products have “not worked”, it is because they have not been applied correctly, or repeated treatments have not been given.

If the lesion isn’t prepared sufficiently (including washing and drying gently), the lesion isn’t sprayed thoroughly or the cows walk through a foot bath during treatment, the outcome is likely to be less successful. The recommended best treatment regime is given in Panel 2.

It should be noted while many farmers may carry out treatment during milking, this contravenes Red Tractor Assurance Standards and should not be encouraged. Higher success rates are also achieved when cows are treated in the crush as opposed to standing (Bell, personal communication).

Figures 3 and 4 show the responses of both mild and severe DD lesions to best practice treatment recommendations (note neither cow was foot bathed on days when treatment was administered).

Prevention – biosecurity, hygiene and foot bathing

Once all cattle with active lesions have been treated, the focus shifts to preventing new infections in the first instance and, crucially, preventing recurrence of dormant (M4) lesions, which are the key driving force behind outbreaks. While there are many components that come into prevention, the key ones are biosecurity, hygiene and foot bathing.

Purchased stock are the greatest risk when it comes to introducing DD into a naïve herd. However, even when DD is present, it is still important to practise good internal and external biosecurity. People are a risk factor for the introduction of DD on to farm, but also between different groups of animals.

If youngstock are naïve then care must be taken not to spread it to this group from affected adult groups, with certain management practices increasing the risk – for example, communal use of a scrapper tractor or gathering the herd for TB testing.

The dirtier the cows, the greater the risk of DD (Figure 5). Keeping cattle cleaner is essential through more effective scraping out, targeted timing of automatic scrapers to periods of least cow traffic and ensuring slurry pooling is minimised in high-traffic areas, such as the collecting yard.

Poor cubicle comfort – leading to perching cows, inadequate ventilation and overstocking – can all increase exposure to slurry and should be addressed where issues are present.

Not only does slurry act as a transport medium for the treponemes, but it also causes the necessary damage to the skin (maceration) to allow the treponemes to penetrate it – therefore, a two-fold benefit exists to improved hygiene.

Foot bathing is commonly viewed as a treatment for DD, although its role is one of prevention – to prevent new infections in the first instance and to also prevent the recurrence of dormant lesions. Flare-ups are common when foot bathing is stopped or where it is only used in the face of an outbreak. Many things should be considered when it comes to foot bathing and these are discussed in Panel 3.

DD has a complex cycle of infection in a herd, requiring an integrated approach to its control. While many unanswered questions remain regarding DD, we have sufficient knowledge to be able to manage it to a very low level. While many herds live with a background level of DD, with a strategic plan in place it doesn’t have to be a hassle for either the producer or the cow.

The photographic material that accompanies this article is from an on-farm case study carried out for Arla Sustainable Dairy Farming Strategy autumn/winter workshops. Further information on the case study demonstrating how DD can be brought under control and kept under control in the long term will be presented at the forthcoming Cattle Hoof Care Standards Board CPD Day (Bristol, 25 April) and The Cattle Lameness Conference (Worcester, 26 April).

Panel 3. The who, what, when, where and how of footbathing

Who: All at-risk cattle are foot bathed, including milkers, dry cows and youngstock. The latter are often overlooked, but heifers suffering active cases of DD prior to first calving are much more likely to have an active case in first lactation, as well as have reduced fertility and lower milk yield (Gomez et al, 2014). Given the length of time it takes for a lesion to develop, it is important to start foot bathing heifers at least three months younger than the age active lesions are first detected at.

What: Relatively few robust clinical trials exist behind many of the chemicals used in foot baths. The aim is disinfection rather than treatment, and both copper sulphate and formalin have been demonstrated to be effective at controlling DD. However, both must be used with caution for differing reasons.

Formalin. While highly effective at concentrations of 2% to 5%, formalin was upgraded to a category 1b carcinogen at the beginning of 2016 and, therefore, a need exists to have strict health and safety measures in place for anyone handling it on farm. This includes training in its correct use and sufficient personal protective equipment being worn during handling, such as a respirator, long gloves, goggles and a chemical suit. Use of automatic foot baths, or a simple system set up with a water-powered proportional dosing pump, can help alleviate handling.

When: How often foot bathing should be carried out is farm-specific and may also vary during the year, with increased frequency during periods of higher risk – for example, more cows calving into the herd. As a general guideline, the dirtier the cows and the higher the herd prevalence, the more frequently foot bathing is required. Since cleanliness can be subjective, it is useful to use scoring systems such as the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board Cleanliness Scoring Chart.

Where: A foot bath is most effective when it is incorporated into the cows’ normal routine, so limited disruption to cow flow occurs. The parlour exit/return lane is commonplace; however, if using formalin, consider distance to the parlour and ventilation. Where foot baths are positioned on the entrance to the parlour, consideration must be given to the risk of cows bringing chemical fumes into the parlour, plus the cost-effectiveness of having a larger bath to account for ease of cow flow.

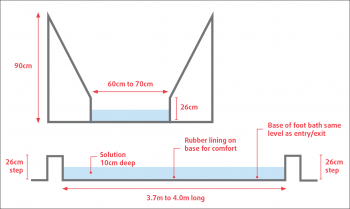

How: Good cow flow through the foot bath is essential to reduce faecal contamination and displacement of the foot bath contents, as well as ensuring minimal disruption to cow traffic. Rigid plastic baths with pronounced ridges on the bottom are uncomfortable for cows to walk through and are not recommended. Instead, permanent built-in foot baths provide better cow comfort and cow flow. Cows do not like stepping up or down into a bath; therefore, the bottom of the bath should be on the same level as the entry/exit points and also provide the cow with grip as she walks. Rubber matting on the bottom of the bath will provide grip as well as comfort as the cow walks through.

Length, width and depth of the bath are also critical. It is recommended each foot should be dunked at least twice – preferably three times – requiring a footbath 3.7 to 4 metres long. As reported by the Dairyland Initiative, reducing the width of the bath to 60cm to 70cm reduces the filling cost, while still allowing cows a comfortable walk through the foot bath (Figures 6 and 7). While wider footbaths are often used for ease of cow flow, these can be costly to fill if they are to be long enough to achieve the required dunks.

Fixing sloping side panels to the edge of the bath helps ensure cows place their feet in the solution rather than on the sides of the bath, as well as reducing loss of solution through splashing.

High entry and exit steps also reduce solution loss and increase the number of dunks achieved, with 26cm steps the recommendation. To ensure feet are completely immersed in the solution, it should be filled to a depth of 10cm. As well as considering cow flow, when designing the foot bath it is important to pay attention to its position and how easy it is to fill, empty and clean. A wide-bore bung can help with rapid emptying and easier cleaning out (Figure 8).

As a rough rule of thumb, for every litre the foot bath holds, one cow should be allowed to pass through – that is, a 240L bath will be sufficient for 240 cows. However, it is not recommended baths are used on more than one occasion as many disinfectants are deactivated in the presence of organic matter.