19 Apr 2021

In this article, Davinia Hinde runs through all the important aspects of the disease vets and keepers of sheep need to know.

Figure 1. Smaller lamb with diarrhoea due to coccidiosis. IMAGE: Fiona Lovatt

Coccidia are single-cell organisms that are host specific and will affect most lambs early in life.

Only two species are pathogenic in sheep (Eimeria ovinoidalis and Eimeria crandallis), but many other non-pathogenic species can be found on faecal examination, and this indicates why speciation of coccidia is so important. Cocci can be found in the intestines of normal, healthy adult sheep without causing any problems and these sheep are often the infective sources, contaminating the bedding and, therefore, providing an infective source for young lambs.

If young lambs are only exposed to low numbers, disease is unlikely and, in fact, this can be beneficial, as it helps provide the lambs with some immunity to the parasite for later in life. If the cocci is present in large numbers and overwhelms the lamb, this is when clinical disease develops. During this period, the lamb also sheds more cocci oocysts into the environment, therefore providing more environmental contamination for other young lambs and increasing the chances of them developing clinical disease.

Coccidiosis can have a significant economic impact on flocks, with decreased weight gains, clinical disease and death arising (Chartier and Paraud, 2012). Lambs become infected after ingesting the sporulated oocysts of Eimeria from contaminated feed, the environment or water. When in the environment, the sporulated oocysts are very resistant. Their survival is mostly limited by exposure to direct sunlight (Chartier and Paraud, 2012).

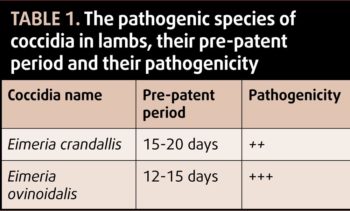

In the UK, clinical symptoms are most often seen in lambs aged between four and eight weeks, depending on species prepatent period (Table 1) and level of challenge. Other factors that influence when clinical disease is observed include genetic susceptibility, physical conditions, and stress factors such as inclement weather and change of diet (Khodakaram-Tafti and Hashemnia, 2017).

Clinical disease is not often seen in younger lambs as they are more resistant to the pathogenic Eimeria due to the presence of maternal colostral antibodies through immunoglobulin G providing protection for up to 40 days (Dominguez et al, 2001).

The main clinical symptom seen is diarrhoea, which can be haemorrhagic, but this is less frequent in lambs than calves. Affected lambs can go on to show dehydration, paleness of conjunctiva, listlessness, abdominal pain, tenesmus and weight loss. Death can be the end result, sometimes without the lamb exhibiting any clinical signs (Khodakaram-Tafti and Hashemnia, 2017). Ongoing poor growth rates in older lambs is often the sequalae of clinical disease as per Figures 1 and 2.

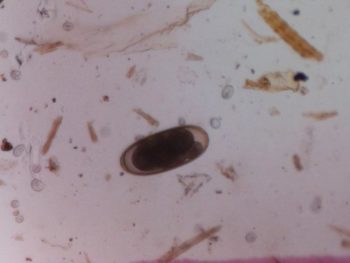

Diagnosis is usually performed by faecal flotations, either in live animals or following on from postmortems. The Eimeria can be speciated to anticipate the pathogenicity of the species in other animals, as well as the pre-patent period of the species. Of the 15 species of Eimeria present in sheep, only the two are pathogenic and, therefore, it is not unusual to have high counts of oocysts without any clinical disease being present (Taylor, 2019). Figure 3 demonstrates the difference in size between Nematodirus egg and cocci.

Any factor that decreases a lamb’s immunity can increase a lamb’s susceptibility to coccidiosis (Khodakaram-Tafti and Hashemnia, 2017), and it is not unusual to find high coccidial counts in faecal flotations during postmortems for other reasons, such as deaths due to Pasteurella pneumonia (Carson et al, 2019). In terms of postmortem findings, nodule formation and thickening of the intestinal wall is often seen. Mesenteric lymph nodes are often enlarged on gross postmortem.

Prognosis depends on the susceptibility of the lambs and the degree of infection with oocysts. Sometimes, death occurs without clinical signs, but in those demonstrating signs, prognosis depends on speed of treatment and correction of other clinical signs, such as dehydration.

Depending on the degree of damage to the intestinal mucosa, lambs can have decreased weight gain for life if they do survive.

Coccidiosis is treated through groups rather than of individual animals. Diclazuril and toltrazuril are both licensed for the treatment of coccidiosis in the UK (Simcock, 2019).

All available products are oral drenches that can be used in the face of an outbreak, and given to lambs from three weeks of age as a preventive measure where coccidiosis has been diagnosed on farm as a cause of clinical disease and speciation has been performed. It may be necessary to repeat dosing with diclazuril after three weeks.

Most ruminants will develop good species-specific immunity, but this depends largely on the dose of Eimeria present. Therefore, pasture contamination for next year’s lambs can still occur (Jolley and Bardsley, 2006).

Key to prevention and control of coccidiosis is environmental hygiene. This helps to prevent naive lambs being exposed to levels of coccidia at any one time that would overwhelm them and cause disease. It can, however, be beneficial to have a low, slow exposure that allows the lambs to develop immunity to the disease (Carson et al, 2019).

Ewes being in good nutrition, with good passive transfer of colostral antibodies, will help prevent against concurrent disease and, therefore, minimise the effect of the Eimeria present. To this end, metabolic profiling of the ewes may well be beneficial, as well as checking the passive transfer status of the lambs through blood samples.

Removing stressors that predispose the lambs to coccidiosis is also beneficial, although this can sometimes be difficult to achieve – for example, protection from inclement weather. Maintaining good hygiene in sheep houses is essential to prevention and control. The areas where lambing occurs should be kept as clean and dry as possible.

Long lambing intervals predispose to more environmental contamination, so attempting to maintain a short lambing period can be beneficial in prevention and control. Minimising mixing of age groups within housing can also help prevent against environmental contamination and, therefore, clinical disease.

Minimising faecal contamination of a ewe’s fleeces, water and feed troughs is essential. Floor feeding should be avoided if environmental contamination is present, especially if overcrowding of the housing is a problem (Khodakaram-Tafti and Hashemnia, 2017).

Diclazuril and toltrazuril are licensed in the UK for the prevention of coccidiosis in lambs. The two products act differently, but both are usually able to allow the lamb to develop immunity (Carson et al, 2019). Decoquinate is an in-feed medication licensed for the prevention of coccidiosis in sheep. It is recommended on veterinary prescription and it is incorporated at a concentration of 100mg decoquinate per kg feed (100 parts per million) for the duration of the risk period and fed for a minimum of 28 days.

Each 10kg lamb must ingest 100g of creep feed a day to maintain adequate decoquinate levels. Decoquinate is also active in the small intestine and animals may still shed occysts from the large intestine, despite eating the medicated feed, and therefore provide more pasture contamination (Simcock, 2019).

Maintaining young lambs on pastures with known low levels of contamination can be beneficial in terms of building up immunity to the coccidia, but this strategy must be taken with caution. When coccidiosis has been diagnosed as a previous pathogenic clinical disease on farm, it is important to treat lambs early to prevent clinical disease from approximately three to four weeks of age. Lambs treated with either diclazuril or toltrazuril shed fewer occysts on to pasture when clinical disease is present. They also have less, or no, diarrhoea and grow faster than untreated lambs.

A single dose of toltrazuril has been shown to be more effective at reducing the number of occysts that are shed into the environment than either a single or double dose of diclazuril, so use of toltrazuril therefore assists in minimising pasture contamination.

Many thanks to Fiona Lovatt, of Flock Health, and Eurion Thomas, of Fecpak, for contributing photographs for this article.