16 Feb 2021

Vaccination of cattle can provide immunity against many diseases that affect the animals during various stages of their lives. Here, Tony Andrews discusses how to raise its benefits with farming clients.

Figure 1. Preparing to undertake a dairy herd vaccination. IMAGE: John Sproat

It is always said “prevention is better than cure”, and this quote has been used by many of us when dealing with vaccination and other disease control measures.

The sentiment is certainly not new, but dates back to around AD58, when the Roman poet Persius said: “Meet the malady on its way.” What seems common sense does not always appear to be so today – especially in human medicine. In these days of fake news, convincing people child vaccination is good can be very difficult until a disease outbreak occurs and people start to die.

Farmers tend to be much more rational and practical than most of the public, but they still need convincing that vaccination is worthwhile. Again, they sometimes only consider vaccination when a disease outbreak has occurred on their farm or when a problem threatens their district or their country.

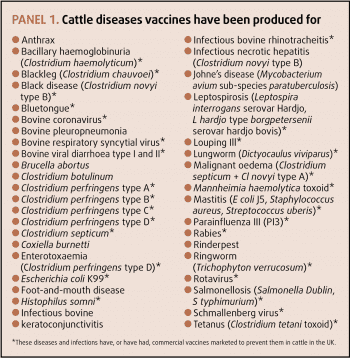

Many different bovine diseases in the UK and abroad exist, against which vaccination can be provided (Panel 1), and some problems have a choice of several vaccines. Farmers cannot use all vaccines, so they need guidance when making a rational choice. They have to weigh up the risks of disease, and also the benefits and financial outlay of vaccination. Optimising a good cattle vaccination strategy requires a trusting relationship and effective communication between the vet and farmer (Richens et al, 2016).

Each vaccination data sheet should be carefully studied to ensure the best results are obtained. When given to calves, some vaccines should not be used under certain ages – usually because of the potential interference of colostral antibodies with the vaccine to produce an active immunity.

In adult animals, it is always best to check if injections can be given during pregnancy and, if so, during the whole of pregnancy. When cattle have a high health status for certain infections then, if vaccine is to be used, any antibody production should be capable of differentiation from field infection – that is, marker vaccines.

Most vaccines should only be used when cattle are healthy and timed to ensure the animals have maximum protection when they are most vulnerable to disease. With some vaccines, this may mean after two vaccine doses and a period for immunity to develop. This at its longest may be six to eight weeks.

Some live vaccines can be used in the face of the outbreak of disease. Therefore, some live intranasal vaccines will produce resistance to the pathogen by interferon production a few hours after administration.

When vaccination is being performed, the organisation of the procedure should be made to ensure it is undertaken as swiftly, and in as stress-free a way, as possible (Figure 1). It is also important to ensure the vaccine is suitably stored prior to injection (Figure 2). The right site should be used for the vaccine, and it should be undertaken as cleanly as possible (Figure 3).

The problem for many farmers is the one of money. Many do not like reaching into their back pockets to find money unless they are convinced of the benefits of vaccination. The skill comes in deciding which vaccines to use on a particular farm and then ensuring they are cost effective.

When vaccines are first used on a farm, it is important to take the time to explain how they work (Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture Alliance; RUMA, 2006a,b) and the probable results to be achieved. This takes much time and effort. The likely cost benefits should also be discussed.

About 20 years ago, the author conducted an on-farm study concerning the cost of respiratory disease in dairy-bred calves and in suckler calves. The trial took a long time to complete and could not have been finished without the enthusiasm of several capable vets and their farmer clients.

It was financed as a leap of faith by the then Pfizer Animal Health, which had no input to the study except to approve the investigation protocol.

The results have stood the test of time, and unfortunately the costs are still believable, as the economics of the farming industry have not increased much in the intervening 20 years. To my mind, this is criminal for farmers and their investment in the future.

The study findings are still quoted; for example, Mahendran (2016) indicated the cost of calf pneumonia in a group of young calves where disease had occurred was £29.58 (the ill animal cost £43.26). These same costs were considerably higher in suckler calves at £74.10 per group member (cost per ill calf was £82.10). Also, on some farms the study continued and further costs from subsequent illness, deaths and culling made the losses appreciably higher.

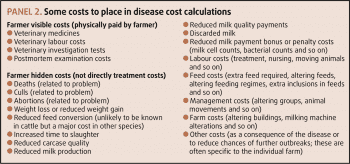

While these costs are partly historical, they did show that in both dairy-bred calves and suckler calves the farmer-perceived costs – namely, what was immediately paid out by the farmer in veterinary visits and manpower – were only about 40% of the total costs. The remaining 60% were the hidden costs (not immediately paid out by the farmer).

The losses included weight loss or reduced weight gain (highest of these hidden costs), mortality, culls, labour costs, materials and other costs (such as altering buildings, improving ventilation, extra feeding, or vitamin and mineral provision). After each outbreak, the costs were discussed with, and agreed by, the farmer as being realistic and correct.

The author has explained the aforementioned because time needs to be taken with the farmer to explain why it is in his or her best interests to invest in a vaccination programme. Determining the costs is far easier to do during, or soon after, an outbreak of any disease. This is the same for all diseases against which vaccines are available.

As in my calf pneumonia example, the costs of the treatment and veterinary involvement are probably best first calculated. However, the other costs – such as labour, extra nursing of ill animals, alterations in their management, lost production (milk or weight gain), mortality, culls and any subsequent costs – should be included. Panel 2 includes some of the cost elements that might be included.

On most farms, not all of these costs will be known, but it is possible to make a best estimate of them with the farmer’s assistance. Then all the seen and unseen costs can be totalled up for the individual infected animal and then for the group or herd. It would be surprising if these did not indicate the benefit of vaccination.

If the disease is not currently on farm, or a previous outbreak cannot be used, a putative percentage infected and requiring treatment can be used. These will be the average numbers of affected animals within herds for most diseases, and often milk testing will indicate the levels of infected animals in the herd (for example, bovine viral diarrhoea or infectious bovine rhinotracheitis).

However, when the author undertook the bovine respiratory disease work, the author had previously considered that, in most outbreaks, about a third would require treatment. However, in this cost study we looked at all cases of pneumonia until one week after the final case, and then again a month after this previous visit.

As it can take time to build up the disease picture on a particular farm, it is often best to use costs for a particular disease that have been calculated within the literature. Many vaccine-producing pharmaceutical companies have such information or computer programs to indicate the costs of a disease. However, when using any general costs it is important they fit into what happens on the particular farm in terms of severity or incidence, so they are believable to the farmer.

One question that often arises when vaccines have been used for several years is “can I stop vaccination?” The answer is complicated, but it is “no”, even if disease has not been seen. In such cases, the argument to the farmer is to calculate how much has been saved annually by not having the disease.

Many of the diseases vaccines are available for can be treated with antimicrobials. Broadly, while vaccination cannot always be 100% effective, it does tend to reduce disease incidence, lower disease severity, reduce its duration and decrease the need for antibiotic usage.

Much better justification can be given for using treatments where preventive measures, including vaccination, have been undertaken, than when the farmer is leaving things to chance.

Some years ago, in anticipation of the need to drastically reduce the quantity of antimicrobial preparations used on farm, the Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture Alliance (RUMA) produced guidelines for vaccination use in general, and also for each major animal production species.

Two versions were produced for each subject, with the fuller, more technical, version for reading by veterinary surgeons, other professional people advising on farms, farmers and farm managers, and a shorter version for those interested in disease generally (RUMA, 2006a,b; 2007a,b).

Most farmers are already well aware of the problem of antimicrobial resistance and the need to reduce antimicrobial usage. It should be a no-brainer to them that vaccination is likely to reduce disease, their disease costs and also their use of treatment. However, some recalcitrant individuals still wish to continue in the same ways when dealing with disease.

If they continue to resist this change, it is likely their own – and everyone else’s – ability to obtain and use antibiotics for necessary disease incidence will be considerably restricted. While antimicrobial use in disease has produced the mantra “as little as possible, as much as necessary”, this is to avoid animal welfare problems. However, the use of vaccines is even more welfare friendly. It prevents the damage to the animal’s body caused by the infection – some of which may be irreparable.

Even if disease still occurs despite vaccination, then it is likely to be less severe and easier to treat effectively. Obviously, this is exactly the same for human illnesses, as well as in animals.

Returning to the author’s introduction, and without being too presumptuous, might he suggest we modernise Persius’ original thoughts to “vaccine prevention is better than antimicrobial cure”?