9 Jun 2020

Oliver Tilling explains the importance of successfully preventing this issue on farms, and describes its causes and diagnosis.

A total of 48.2% of all calves in the UK suffer from scour1 (Figure 1). It is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in preweaned calves2, accounting for up to 50% of all preweaned mortality3.

In severe outbreaks, scour can cause 20% mortality of affected calves4. But calf mortality only represents a small proportion of the financial damage an outbreak can cause.

Scour costs at least £44 per calf affected, excluding labour5. Additionally, a delay exists in reaching age at first calving and lower yields in first lactation.

Many infectious and non-infectious causes of scour exist – and as clinical signs are general, it is not possible to identify or predict a specific cause from clinical signs alone.

The infectious bacteria, viruses and protozoa that cause scour are important, but they can also be found on farms with and without clinical disease. Furthermore, mixed infections with one or more agents are common.

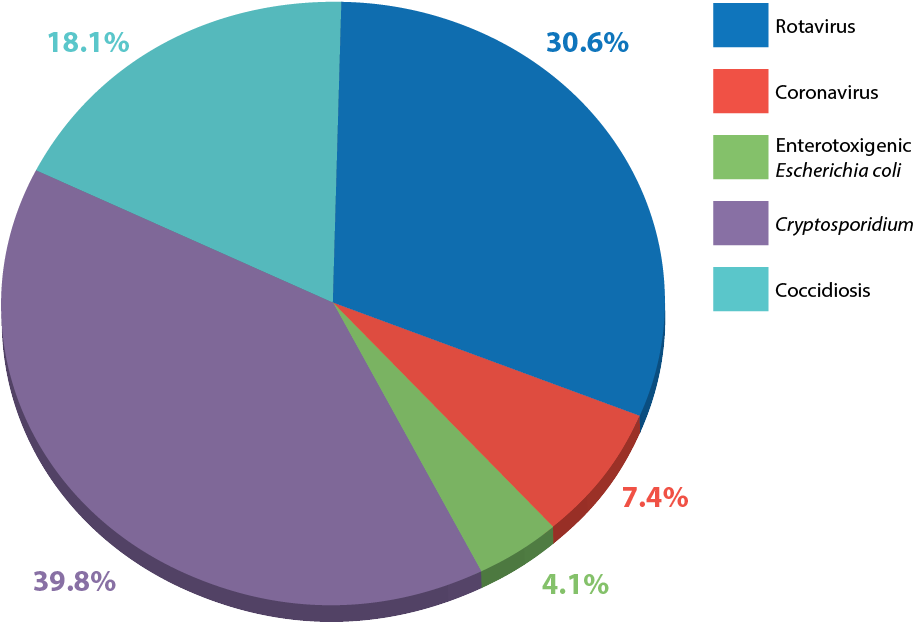

Although many infectious agents have the potential to cause scour in calves, currently six pathogens are significant:

Figure 2 shows their frequency of diagnosis in the UK between 2011-20186.

Non-infectious scour – usually referred to as a nutritional scour – is a result of a disruption to normal feeding patterns.

Diagnostic testing will influence treatment, prevention and control strategies, which vary for the different infectious causes of scour. A thorough history and observation of feeding management will help determine if a nutritional scour is occurring.

Collection of six faecal samples (minimum 15g each) from untreated calves in the early stages of disease gives the best possible chance of a diagnosis. Samples must come direct from the rectum and not the floor, where they would be contaminated. Samples should be tested for all potential causes of infectious scour, while taking into account age of animals affected and clinical signs.

If any calves have died then a postmortem examination (Figure 3) is an excellent way to reach a diagnosis – preferably at an approved laboratory where any necessary follow-up testing can be performed. Calves must have died less than 24 hours earlier to give the greatest opportunity of reaching a diagnosis.

Irrespective of the causal agent, route of infection for infectious calf scour is the same – ingestion or inhalation of the organism from an environment heavily contaminated by faeces.

Hygiene, cleanliness and good colostrum management are paramount, and, along with suitable nutrition, are the key to prevention and control of calf scour.

Good hygiene must start from the moment the calf is born, as many infections are picked up from the calving area. Hygiene and cleanliness must be maintained throughout the calf-rearing period, with specific care taken to clean and disinfect feeding equipment between feeds (Figure 4), and to thoroughly clean the environment on regular occasions and between batches of calves (Figure 5).

Scour is 1.9 times as likely when calves are reared on wet bedding and 0.6 times as likely when disinfection is carried out between groups7.

The following protocol at two-weekly intervals (more if heavy contamination or high stocking rates) will ensure a suitably clean calf environment:

General farm disinfectants are usually satisfactory. However, Cryptosporidium oocysts are highly resistant and persist in the environment for long periods of time, so suitable disinfectants in this situation include:

Effective colostrum management requires a focus on the five Qs:

Ensuring all calves receive adequate quantities of clean, good-quality measured colostrum within the first four hours of life will provide the essential immunity a calf needs to fight off scour and other pathogens.

Having protocols in place to regularly monitor colostrum management will encourage farmers to maintain high standards, but also identify if the system is failing.

Vaccination is available for many infectious scour organisms – specifically vaccines for rotavirus, coronavirus and ETEC; a vaccine is also available for Salmonella. Both vaccines require vaccination of the cow during the dry period or the heifer as she approaches calving (it is possible to also vaccinate healthy calves aged three weeks and older for Salmonella).

A vaccine is not a substitute for good management and both vaccines rely on good colostrum management to ensure immunoglobulins are passed from cow to calf.

Some causes of infectious scour have specific licensed treatments – for example, halofuginone for Cryptosporidium. Halofuginone can be used as both a treatment and preventively. It reduces disease severity and oocyst output – minimising further spread.

On a group basis, prophylactic use of halofuginone can prevent further scour due to Cryptosporidium after a diagnosis has been made. The drug is given daily for seven days. It has a narrow safety margin and is toxic at twice the therapeutic dose, so ensure clients administer the correct dose.

Calves that have had scour for longer than 24 hours should not be treated with halofuginone, and dehydrated calves should not be treated unless on oral fluids.

When feeding calves, we are not just feeding for growth, but feeding their immune system. To an undernourished calf, an immune system is a luxury it can’t afford.

Adequate consistent feeding of calves reduces the risk of both nutritional scour and infectious scour developing:

Anyone who is involved in the calf feeding must be aware of the routine. Clear lines of communication should be in place between staff – such as a diary; a noticeboard in the calf shed; and telephone calls, text messages, WhatsApp or email to pass on relevant information.

The routine should also include regular assessment of the success of the feeding programme in conjunction with the vet, which will include monitoring performance and record‑keeping.

With such high endemic levels of calf scour in the UK cattle population, cattle practitioners must help their clients address this costly disease. The idea that “calves just scour” is simply unacceptable and straightforward ways exist to address this.

Cleanliness and hygiene, effective colostrum management and adequate consistent feeding form the basis of this. Judicious use of vaccines and other preventive therapies will further help in the defence against this disease.