9 Apr 2021

James Breen, BVSc, PhD, DCHP, MRCVS provides responses to some commonly posed questions and misconceptions surrounding this controversial concept.

The administration of antibiotic dry cow therapy to all quarters of all cows at drying off has been a mainstay of contagious mastitis control in the UK and other countries for many years. The use of antibiotic dry cow therapy at drying off continues to be one of the most important roles for antibiotic use in dairy herds, as the chance of cure for infected cows is very high during the dry period – indeed, the chance of cure is much higher than at any time during lactation – making rational use of antibiotic dry cow therapy a very prudent use of antibiotic.

However, for many cows in UK herds the likelihood of infection with a major pathogen at the time of drying off is very low – and, therefore, prevention of new intramammary infection in these cows is key and research worldwide has demonstrated that the use of internal teat sealants at drying off significantly reduces the risk of new infection. Therefore, the selective use of antibiotic dry cow therapy is important not only for rational prescription of antibiotic dry cow therapy, but for other reasons including welfare of the cow; UK research has demonstrated that the use of dry cow antibiotic in low cell count cows increases the risk of coliform mastitis in the next lactation.

Despite many research papers, presentations and discussions, the concept of a selective approach to antibiotic dry cow therapy remains controversial and questions remain around decisions at drying off, identification of infected and uninfected cows, and monitoring herds over time.

Following the publication of the O’Neill report in 2016 and the Government’s response to recommendations, the Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture (RUMA) Alliance introduced sector-specific guidelines on antibiotic use and targets that were to be met by 2020 (RUMA Alliance, 2017).

For dairy herds, this included a 20% reduction in the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy, as well as a 10% reduction in the use of intramammary antibiotic used in the treatment of clinical and subclinical mastitis.

While other measures in the dairy sector are aimed at large-scale reductions in the use of high-priority, critically important antibiotics and a significant increase in the use of internal teat sealants, a selective approach to the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy is perhaps causing the most confusion regarding the likely impact on cow welfare and herd mastitis control.

As it remains a contentious issue for many vets and farmers, this article seeks to update veterinary surgeons in practice with responses to commonly posed questions and misconceptions.

For many herds and their veterinary advisors, a key driver of a selective approach to the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy is that this must surely reduce herd antibiotic use. Unfortunately this is not necessarily the case – particularly when compared to other drivers of antibiotic use in dairy herds, such as antibiotic footbath products and injectable antibiotic use.

A study looking at antibiotic use in 358 UK dairy herds showed that the impact of antibiotic dry cow therapy on overall herd mg use was very small, accounting for just 2mg/population corrected unit (PCU) to 3mg/PCU (Hyde et al, 2017).

Antibiotic dry cow therapy is excluded from calculations of defined daily doses as per European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption European Medicines Agency methodology, but is included in calculations of defined course doses (DCDvet). The latter averaged 1.93 DCDvet across the 358 herds in the Hyde study; the prescription of antibiotic dry cow therapy to every cow in a herd would result in a DCDvet of 1 (that is, 1 course of antibiotic to every cow), so reducing the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy will only reduce the courses for those situations where this metric may be more important.

The importance of an aseptic infusion technique when administering any form of intramammary product – dry or lactating cow – is well understood, but the unhygienic administration of an internal teat sealant to uninfected cows is the most readily appreciated situation of where a selective approach to antibiotic dry cow therapy can go “wrong”.

It is important that we, as a profession, can “push back” on claims that it is “impossible” to do this, and instead provide training and periodic supervision or assistance to ensure a consistent approach. Videos have been produced by the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board Dairy to illustrate an aseptic approach to infusion and may help veterinary surgeons in practice to gain confidence before they advise their own clients (Figure 1).

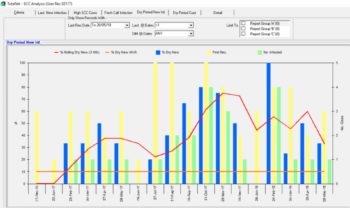

The use of a standard operating procedure that is routinely sent out with every dry cow therapy prescription to remind clients is useful – particularly if this is accompanied with cotton wool and surgical spirit. The lack of an aseptic infusion technique can be readily observed by monitoring clinical mastitis and cell count data, the latter illustrating situations where infusion technique may be poor (Figure 2).

It is also important to resist claims that mastitis shortly after drying off is the result of bacterial infection that has been “sealed in”, leading to disease following infusion. This is simply not the case, with research demonstrating that glands already infected with a major pathogen do not develop mastitis during the dry period – instead these infections may cause issues in the next lactation if they fail to cure (Bradley et al, 2015).

For many herds and their veterinary surgeons, this remains a key “sticking point”, with a real concern that a relatively low sensitivity for many tests at drying off will result in missing cows that are truly infected.

While some wrong decisions will always be made, the practitioner also needs to appreciate the potentially damaging consequences of administering antibiotic dry cow therapy to cows that are not infected.

In well-managed, low somatic cell count herds (bulk milk somatic cell count below 200,000cells/ml) the prevalence of infection will be relatively low, and therefore many more cows will be uninfected at drying off. This means that typically cautious approaches – whereby only very low cell count cows are selected for internal teat sealant alone – will result in a) many cows receiving antibiotic dry cow therapy that don’t need it, and b) the risk of cows with severe mastitis after drying off in those herds that are starting out with this approach and are unfamiliar with aseptic infusion technique/are not doing enough to become practised.

Ultimately, even if some cows are “missed”, we have to ask ourselves what are the consequences of a missed infection, and then how many are we likely to miss.

For example, a cow is dried off with internal teat sealant alone as her last three somatic cell counts are less than 200,000cells/ml and she has not been detected with clinical mastitis for the past three months.

Let us assume she is in fact infected with Streptococcus uberis – what are the likely consequences?

How many major pathogen infections are we likely to miss? Work from Canada investigating culture at drying off to inform decision‑making looked at 360 cows from 16 herds, all of which had the previous three somatic cell counts prior to drying off less than 200,000 cells/ml, had not been detected with clinical mastitis for the past three months and had not received antibiotic in the past 14 days (Cameron et al, 2013).

Based on the bacterial culture results of samples taken the day before drying off, using individual cow somatic cell count in this way missed 1.2% of quarters infected with an environmental Streptococcus species and 0.5% quarters infected with S aureus. Clearly, in many herds this is acceptable given the huge proportion of quarters that are uninfected and for which antibiotic treatment is not warranted.

Some debate remains about cows at drying off with very low somatic cell counts – that is, individual cow cell count of less than 50,000cells/ml and certainly less than 20,000cells/ml. These cows are at increased risk of new infection during the dry period and previous work has shown that administration of antibiotic dry cow therapy with extended Gram-negative spectrum results in a significant reduction in clinical mastitis in the next lactation (Bradley and Green, 2001).

However, in all the studies that the authors have worked on since the inception of internal teat sealants, these cows have not received antibiotic dry cow therapy.

It is also worth reflecting on the issues around sealant retention in the presence of antibiotic dry cow therapy, with more recent work showing that quarters receiving antibiotic dry cow therapy and internal teat sealant in combination were significantly less likely to recover the full 4g of bismuth subnitrate after calving – suggesting an effect of the antibiotic dry cow therapy on sealant retention (Bradley et al, 2010).

The increase in risk of new infection after drying off related to increases in milk yield prior to drying off is a well-recognised issue in the modern dairy herd.

Work from 29 herds in south-west England showed that milk yield prior to drying off had increased from an average of 8.9 litres in 1999 to 17.8 litres in 2015. Based on previous UK work, as a result of this increase in milk yield, on average, cows in these herds are now around 1.8 times the risk of acquiring a new infection in the dry period compared to the cows in these herds in 1999 (Bradley and Green, 2015).

While many practitioners and farmers feel that prescribing antibiotic dry cow therapy will mitigate this increase in risk, it must be remembered that all the past research demonstrating increased risk of new infection was in the presence of antibiotic dry cow therapy.

Ultimately, the risk posed by increased yield at drying off should be reduced by strategies that reduce milk yield, and these may be aimed at individual cows (regrouping, isolation, diet change) or with pre-drying off groups.

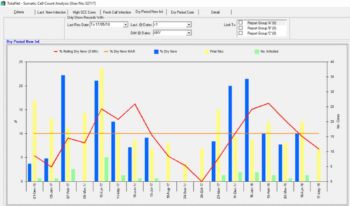

Again, monitoring data will often disprove the practice of using antibiotic dry cow therapy in combination with internal teat sealant during periods of increased environmental challenge (“We dried the low cell count cows off with antibiotic because we knew the pressure on the straw yards would be high this winter”), with increases in new infections readily demonstrable in herds despite using antibiotic (Figure 3).

Correct – none of the tests at drying off can ever definitively categorise a cow as infected or uninfected; even bacteriology is imperfect. Despite this, a selective approach to antibiotic dry cow therapy is not a waste of time – we just need to accept that we will make some wrong decisions (and by using antibiotic dry cow therapy in combination with internal teat sealant we are making some wrong decisions now).

Although much interest exists in on-farm culture to make decisions about antibiotic dry cow therapy, we must remember that bacteriology also has issues with test sensitivity (some infections may be missed – for example, intermittently shed pathogens, non-viable pathogens, inadequate incubation period and so on) and specificity (growth of some organisms may be deemed significant – for example, interpretation of non-aureus Staphylococcus species).

The Canadian study mentioned earlier highlighted a positive predictive value of 70% for bacteriology, meaning around 3 in 10 of treatment decisions will be incorrect, and this is assuming that a decision to treat a non-aureus Staphylococcus species is “correct” (Cameron et al, 2013).

Similarly, the use of the California Mastitis Test (CMT), while useful at the beginning of lactation to highlight infected quarters, suffers from similar issues with sensitivity and specificity, but particularly the latter, with an increased number of false positives likely due to the normal pattern of increasing cell count in late lactation cows as milk yield is reduced. While in high cell count herds this may be less of a problem, in low cell count, low prevalence herds the use of CMT alone or in combination with cell count is likely to result in overtreatment of quarters with dry cow therapy.

The quarter-level approach to dry cow therapy is receiving attention due to the perception that this will target treatment (possibly) and therefore reduce antibiotic use (the latter as we have seen is very marginal).

It may be that treating infected quarters with antibiotic dry cow is a logical step forward from selective antibiotic dry cow use at the cow level, but the practitioner should pause and ask questions around the tests we are using to identify infected quarters – what are the thresholds for infection? What is the likelihood of a false positive or false negative?

Currently, the best advice is to treat at the cow level as quarters are not independent within a cow – although this advice may change with new research – and research is currently ongoing.

Perhaps the most concerning trend is those herds that have removed antibiotic dry cow therapy completely or are restricting the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy in combination with internal teat sealant to only those cows with very high cell counts at drying off (for example, greater than 500,000cells/ml or similar).

We must remind herds of the importance of the dry period for a time to cure existing infection, and even in low cell count herds (especially in higher cell count herds) there will be cows that are infected; therefore, the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy in combination with an internal teat sealant is an entirely rational decision and responsible use of antibiotic.

Claims that “nothing has gone wrong” are, of course, invalid – the consequence of missing some infected cows now will not be immediately felt – but missing infected cows over a longer periods of time will inevitably result in a higher prevalence of infection at calving, with consequences for the bulk cell count – and the importance of monitoring data becomes clear.

Ultimately, the profession should continue to promote the use of internal teat sealants at drying off in all cows and remind clients that a selective approach to the use of antibiotic dry cow therapy is based on the effectiveness of internal teat sealant to prevent new intramammary infection in uninfected, low cell count cows.

A meta-analysis (the highest level of research evidence) is available on the use of internal teat sealants and highlights the significant reduction in the risk of infection (Rabiee and Lean, 2013).

While all these questions are valid and important, we come finally to the most important question of all when making decisions about dry cow therapy – “How will the dry cow environment be managed?”

Too often we still come across situations where the environment of the dry cows is not managed to the same standard as the milking cows – only bedded up three times a week, only scraped through once daily and so on.

For many herds this represents the most important pressure on risk of new infection – particularly when our low cell count cows that are giving 25 litres at drying off are dried off into a straw yard that is overstocked, poorly ventilated and only cleaned out every four to six weeks (Figure 4) or dried off into a paddock that has been in use for four weeks already.

Advise and prescribe dry cow therapy responsibly, and use evidence to help us – but don’t forget to follow these cows through the dry period, and use this opportunity to review current husbandry and environment management.

The author would like to acknowledge: