18 Dec 2017

Russell Parker describes non-septic and septic osteitis in horses, considering the signs, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.

Pedal osteitis is a general term used to describe inflammation of the distal phalanx – the lack of a medullary cavity in this bone makes osteitis the appropriate term, rather than osteomyelitis.

Broadly speaking, two forms of osteitis are recognised: non-septic and septic, depending on the presence of infection.

Non-septic pedal osteitis is a poorly defined, somewhat nebulous, condition describing inflammation of the distal phalanx. Chronic inflammation with a traumatic aetiology is the most common primary form, as a consequence of exercise on hard surfaces usually affecting the weight-bearing front feet. Alternatively, osteitis may develop secondary to focal blunt solar trauma or other disease processes, such as laminitis. Horses with poor quality, thin-soled feet, such as Thoroughbreds, appear predisposed.

Lameness is variable and may be transiently exacerbated by foot-related incidents, such as farriery or worse, during the summer months when the ground is hard. In bilaterally affected individuals a general restriction of gait, or performance loss, may be more appreciable rather than overt lameness. Visual assessment may identify individuals with poor foot conformation at increased risk. Clinical examination may reveal heat in the hoof capsule and elevated digital pulse amplitude, but this is not always present.

The application of hoof testers is usually resented, either focally or over the entire foot, depending on the scale of the lesion, but this response is not always as obvious as one would expect. Lameness is usually significantly improved by a palmar digital nerve block.

Good quality radiographs of the foot are the most commonly employed imaging modality. Lateromedial and dorsopalmar radiographs are useful for the assessment of foot balance and conformation, which can dictate future remedial farriery. The distal phalanx is best assessed with the standard dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique (upright pedal) projection and oblique projections of the palmar processes.

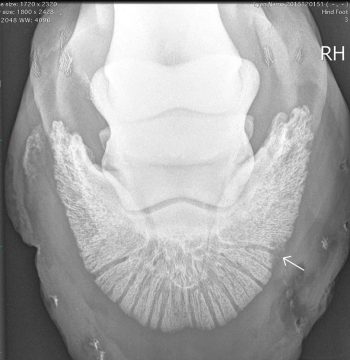

Pedal osteitis is characterised by radiolucency of the distal phalanx and irregularity of the solar margin, with irregular new bone formation in chronic cases (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the appearance of the solar margin in clinically normal horses varies widely (Rendano and Grant, 1978) and any radiographic changes must be consistent with the clinical picture. It should be noted the notch in the dorsal margin of P3 (crena solearis), seen on the upright pedal projection, can vary in appearance and is a normal finding.

MRI may be performed under standing sedation (low field) or general anaesthesia (high field) if radiographic changes are equivocal, or there are other radiographic findings of unknown significance. MRI findings consistent with non-septic osteitis include diffuse fluid signal within the laminae and solar margin of the distal phalanx. Focal laminar haemorrhage is seen as discrete areas of low signal due to the ferrous artefact. However, horses with capsular foot pain, including non-septic pedal osteitis, frequently have limited findings on MRI, and diagnosis is often one of exclusion rather than a positive finding.

In acute cases the horse should be rested with routine anti-inflammatory medication, while the inflammation resolves. Avoidance of exercise/turnout on hard ground is ideal for the ongoing management of these cases, but is clearly not practicable for athletes, which are required to compete in those conditions. In these cases, remedial farriery is key to maintaining soundness, and should focus on optimising foot balance and break over with some form of solar protection at the time of year when the ground is hard, such as a firm pad or gel insert.

Acute cases with a single traumatic aetiology respond well with treatment. Horses with chronic inflammation or conformational deficits, which predispose them to osteitis, are more challenging, particularly if exercise on hard ground is unavoidable. In these cases, lameness is managed rather than resolved, with varying degrees of success.

Septic pedal osteitis is defined by bacterial infection of the distal phalanx that most commonly arises as a sequel to subsolar/laminar abscessation. Other causes include penetrating solar injuries, deep cracks in the hoof capsule or keratoma – all of which allow egress of bacteria into the laminar or subsolar tissue.

In the acute stages, lameness is usually moderate to severe, with clinical signs indicating inflammation of the foot (elevated digital pulse amplitude, heat in the hoof capsule). As with a standard foot abscess, the application of hoof testers will often produce a localised pain response. However, in many cases, the horse may have been treated for a foot abscess some time before it is presented for veterinary investigation, and the level of lameness can be variable.

Removal of the shoe and exploration of the white line will often reveal a discharging tract, but this is not always apparent, particularly in cases with generalised white line disease. Solar penetrations are usually obvious, but the tracts can seal very quickly in some cases.

Radiography is often sufficient to achieve a diagnosis and reveals a focal area of poorly defined radiolucency in the solar margin, if associated with a laminar abscess (Figure 2). However, radiographic changes are often subtle in the early stages and repeat radiographs are recommended 10 to 14 days later if clinical signs are still suggestive of deeper infection that is not resolving.

Differentiating between a keratoma and septic pedal osteitis can be challenging, particularly as both conditions may be present concurrently. However, a keratoma tends to produce a more discrete defect in the solar margin, with less diffuse radiolucency, compared with a pure septic osteitis. Penetrating injuries also lead to focal areas of bone lysis and, potentially, sequestrum formation (Figure 3), which can initially be subtle.

In horses with definitive radiographic findings, further imaging, such as MRI, is not usually necessary and often contributes little to case management. In cases with more subtle radiographic changes, or those in which a penetrating injury has been sustained close to significant soft tissue structures, MRI is helpful in providing a diagnosis, guiding surgical treatment and giving some idea of a prognosis.

MRI findings include inflammatory fluid signal within the affected parts of the distal phalanx and the tract itself is usually seen as a poorly defined area of low signal within the laminae or solar tissue (Figure 4). A sequestrum is seen as a discrete area of low signal (Figure 5), but can be hard to distinguish from focal haemorrhage in some cases. MRI also allows evaluation of important soft tissue structures, such as the insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon and the synovial structures.

Once infection is established, prolonged antimicrobial therapy is usually unsuccessful and surgical debridement is necessary to remove infected tissue and establish drainage. Penetrating injuries involving a synovial structure, in addition to septic pedal osteitis, present additional surgical challenges and are not discussed further in this article.

In cases with a discharging tract, the site of surgical debridement is obvious, but in those without a tract the use of preoperative diagnostic imaging with radio-opaque markers is useful to guide the surgical approach. Prior to surgery the hoof capsule is rasped, pared and scrubbed with povidone iodine to reduce bacterial load. In chronic cases, significant deformity of the hoof capsule may exist, which should be addressed prior to surgery.

Preoperative antimicrobial therapy is ideally dictated by bacterial culture and sensitivity. However, if this is not available, potentiated sulphonamides or oxytetracycline are the author’s routine choice. Standard NSAID medication usually provides adequate postoperative analgesia, but, in severe cases, additional analgesic options (opioids, epidural medication or perineural analgesia) may be required.

Debridement may be performed under general anaesthesia or standing under chemical restraint and perineural analgesia. This decision is dictated by surgeon preference, the location and extent of the lesion, and the temperament of the animal. Routine sedation protocol at the author’s hospital involves acepromazine, morphine and a continuous rate infusion with detomidine.

The foot is desensitised with an abaxial sesamoid nerve block using either mepivicaine or bupivacaine – depending on the anticipated duration of the procedure. A tourniquet is placed at the level of the pastern/fetlock and is mandatory to control haemorrhage, which is otherwise profuse. The surgical approach is dictated by the location of the lesion, but should aim to achieve debridement via the smallest possible defect in the hoof capsule.

For laminar infection, debridement initially starts at the white line on the solar surface, extending up the laminae as far as possible. A partial hoof wall resection is then performed using a trephine or rotary tool to access the laminar tissue further proximally, while maintaining an intact bridge of hoof capsule at the weight-bearing surface (Figure 6).

Partial wall resection was found to lead to reduced postoperative complications, improved postoperative comfort and a quicker return to exercise (Boys-Smith et al, 2006) in horses undergoing keratoma removal – and, in the author‘s experience, the same is true in cases of septic pedal osteitis. Infected laminar or solar tissue is discoloured, with disrupted architecture, and is removed using curettage along with any necrotic bone. After debridement is complete a pressure dressing is applied to the foot before the tourniquet is released to control haemorrhage.

Dressings and antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory medication are maintained while the wound granulates, and a hospital plate is fitted to the foot 5 to 10 days after surgery to protect the defect in the medium term. Keratinisation of the granulation tissue usually takes six to eight weeks, after which, the defect can be filled with acrylic and the foot managed as normal. Most horses resume light-ridden exercise approximately three months after surgery, unless a significant soft tissue injury exists, which prolongs the rehabilitation period.

Clinical experience and the peer-reviewed literature suggest an excellent prognosis for a full return to athletic soundness with appropriate surgical debridement (Cauvin and Munroe, 1998; Gaughan et al, 1989; Lindford et al, 1994). Complications primarily involve healing of the hoof wall defect, but are usually manageable and recurrence of sepsis is unusual if the initial debridement was effective.

Return to exercise is usually dictated by the extent of the hoof capsule defect after surgery, but most horses are ready to resume ridden exercise within three to six months.