19 Apr 2022

Zoë Gratwick BVSc, MSc, MMedVet, DipECEIM, MRCVS outlines causes and considerations to be taken when looking at these indicators of disease in equine patients.

Image: © pimmimemom/ Adobe Stock

Polyuria (PU) and polydipsia (PD) can be indicators of significant disease; therefore, their presence should prompt further investigation. This will often enable appropriate management and, therefore (depending on the issue), may lead to a better prognosis. PU/PD can also be frustrating for horse owners, leading to frequent stops during exercise and an increased workload in the stable.

To meet their maintenance requirements, healthy horses require an intake of 25ml/kg/day to 70ml/kg/day of water1,2. Healthy horses usually produce 15ml/kg/day to 30ml/kg/day of urine3.

When suspicious of PU/PD, the first step is to establish whether water intake is increased.

PD in adult horses can be defined as consuming more than 100ml/kg/day of water. However, it can potentially be present when more than 60ml/kg/day is consumed, as factors such as low ambient temperature and high grass water content reduce the basic drinking requirement.

PU can be defined as production of more than 50ml/kg/day of urine. It is rarely practical to measure the urine output of an adult horse and, for this reason, water intake alone is often more useful, alongside subjective assessment of urine output.

Numerous physiologic methods of water loss exist, such as in faeces (major route), via the respiratory tract and in sweat.

Horses exercising in a warm environment or encountering substantial water losses because of large colon disease may consume water in excess of 100L/d without a corresponding increase in urine volume4.

Increased frequency of urination can be mistaken for increased volume of urination and this ought to be considered when water intake is normal.

If PD is present, the next question is whether this is directly due to an increase in thirst, or whether it is secondary to PU: which came first?

An understanding of normal water homeostasis facilitates a systematic approach to PU/PD.

Normal water homeostasis requires adequate pituitary release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), a functioning renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, adequate renal function and sensitivity of nephrons to ADH. Disruption of any of these processes may limit the ability to respond to changes in water balance and can result in PU/PD.

ADH is produced in the hypothalamus and stored within the pituitary. It is released primarily in response to increased plasma osmolarity, which is detected by hypothalamic osmoreceptors. ADH acts on the distal renal tubule and collecting ducts to promote the absorption of water into the renal medullary interstitium, with the subsequent production of more concentrated urine.

Renin is released from the renal juxtaglomerular cells in response to a decreased circulating volume. This leads to angiotensin II production, which directly stimulates sodium and water resorption in the proximal renal tubule. It also prompts aldosterone release, which subsequently stimulates sodium resorption in the distal renal tubule. Angiotensin II is also partially responsible for stimulation of thirst.

PU/PD can occur as the result of diseases that either increase water consumption directly or where diuresis is the driving factor.

This describes an increase in thirst due to physiologic requirement. For example, following exercise, during hot weather or while lactating. Increased intake may also be seen following fluid loss due to haemorrhage or diarrhoea.

Psychogenic PD describes when horses choose to drink an excessive amount, without an increased water requirement. This is poorly understood, but is typically thought to be associated with boredom or stress5. The presence of pain may also be a possibility.

Horses with psychogenic PD can drink vast volumes and water intake is typically greater than that seen with other causes of PU/PD. When this is protracted, renal medullary washout can develop, resulting in a loss of renal concentrating ability.

Systemic diseases such hepatopathies or those involving endotoxaemia may also lead to PU/PD. The reasons for this may be multifactorial, but are incompletely understood in the horse.

Regardless of the cause of renal disease, a reduction in renal concentrating ability can lead to water loss and a subsequent requirement for increased water intake.

Multiple mechanisms have been postulated for the development of PU/PD in horses with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID). However, none of them seem likely to represent the full picture.

Suggestions have included PU/PD secondary to glycosuria or hypercortisolaemia (not that common in PPID cases6), and development of central diabetes insipidus due to direct pressure from an expanding pituitary pars intermedia.

The kidney’s ability to concentrate urine is impaired when high levels of solutes such as sodium or glucose are present in the filtrate. Diabetes mellitus is uncommon in the horse, but can occur, sometimes leading to glycosuria.

Although stress does not typically cause glycosuria in horses, it is reported to be observed in some cases suffering from chronic or severe stress.

Neoplasia or the use of parenteral nutrition can lead to hyperglycaemia, which can lead to glycosuria.

In the absence of renal disease, high urine sodium levels would typically (albeit uncommonly) be due to excessive dietary salt supplementation, or overzealous salt lick consumption.

Central diabetes insipidus describes inadequate production of ADH, leading to a reduction in the ability of the distal tubule and collecting ducts to concentrate urine. This is thought to be rare in horses, but has been reported idiopathically and alongside encephalitis.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus describes an inability of the kidney to respond to ADH despite the availability of an appropriate amount. This is thought to be uncommon, but can occur alone or alongside other disease states.

In addition to the aforementioned reasons, administration of medications such as alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, diuretics and steroids can lead to diuresis.

Any cause of a sustained increase in water intake can lead to renal medullary washout. This loss of hypertonic medullary interstitium leads to an inability to concentrate urine. This is thought to be seen most commonly due to psychogenic polydipsia.

Clarify whether PD is present: is water intake more than 100ml/kg/day? If so, obtain a clinical history and perform a thorough clinical examination. This may give important clues regarding possible causes. Further information can be gained by the following.

Often (but not always) azotaemia will be present in cases with renal failure.

Disease in other organs may be suggested. For example, if gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), glutamate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase or aspartate aminotransferase are increased, hepatic disease could be a consideration.

PPID may be suggested by an increase in ACTH concentration.

However, plasma ACTH can be increased by physiologic stress or pain, and may also be normal in affected animals. If suspicious of PPID despite a normal or “equivocal” ACTH concentration, a thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test should be performed.

If urine specific gravity is 1.008 to 1.012, renal concentrating ability is likely to be affected.

If urine specific gravity is less than 1.008, increased water intake or diuresis are likely.

Other indicators of renal disease could include an increase in GGT:creatinine ratio, an increase in urine protein:creatinine ratio, or the presence of renal tubular epithelial cells or casts.

Glycosuria may be observed and could reflect PPID, primary diabetes mellitus, severe physiologic stress or administration of alpha-2 adrenergic agonists.

Occasionally urinalysis results might prompt further testing for altered renal function – for example, assessment of fractional electrolyte excretion ratios.

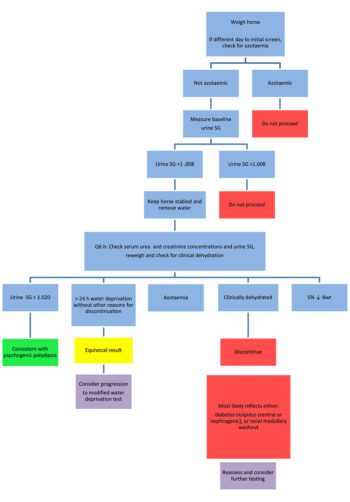

If no evidence is present of PU being caused by renal failure, PPID or other systemic disease, psychogenic PD, renal medullary washout or diabetes insipidus are likely causes. This can be investigated further by a water deprivation test (Figure 1), or a modified water deprivation test (Figure 2).

The primary purpose of this testing is to determine whether the horse can produce concentrated urine.

These tests must not be performed on azotaemic horses, or those suspected to have renal compromise.

If concluded that PU/PD is truly present, a number of causes should be considered.

Psychogenic PD, PPID and renal disease are thought to be relatively frequent causes, with other reasons such as diabetes insipidus being uncommon. A systematic approach will help to safely determine the reason for these symptoms.