19 Jan 2022

Graham Duncanson BVSc, DProf, MSc(VetGP), FRCVS explores issues relating to this common procedure by analysing his first 4,000 cases – as well as a couple of “disasters”.

Castration of normal animals is probably the most common surgical procedure carried out by primary care practitioners in equine practice.

In this article, I am going to explore the problems related to the surgery by referring to the first 4,000 castrations I carried out in practice. I will describe my disasters, but hope to reassure the readers of their extremely low incidence. Of course, these disasters loom very large in my memory.

Naturally, rig animals were found at surgery or reported by owners before surgery was commenced. These are not included in my figures. Historically, castrating rigs would have been tackled by experienced primary care veterinarians; I suspect nowadays referral is more common.

The first 22 straightforward castrations were carried out in Kenya, while 15 were carried out during locum spells in Western Australia and the rest in the UK.

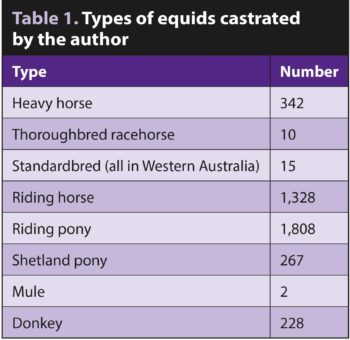

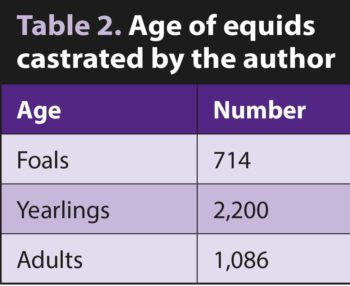

It was an unusual caseload, with very few racehorses and a large number of donkeys (Tables 1 and 2).

In my area of Norfolk, the myth that equine skeletons do not mature in a normal manner if gelded as foals is not believed – many owners request their foals to be castrated while still suckling their mothers. It has been my experience that foals recover from what I believe is a serious surgical intervention with considerably less stress.

I consider the easiest and safest place to carry out a castration with a short‑acting general anaesthetic is in a large dry paddock. The vast majority (3,909) of my cases were castrated in paddocks.

Only 67 were castrated in a knockdown box at the owner’s request. Sadly, through force of circumstances, I had to castrate 24 animals in totally unsuitable conditions (Figure 1).

All my castrations were carried out under a short‑acting anaesthetic. I am sure if I had been working in a racehorse practice, I would have been forced to carry out the surgery on the standing animal because of the unproven myth that a general anaesthetic adversely affects a horse’s racing potential.

The development of short‑acting anaesthesia was relatively rapid through the early years of my career. The first 22 castrations in Kenya were carried out after premedication with acepromazine (ACP) with a bolus of thiopental.

The recoveries were often far from ideal; however, the use of courageous, dedicated staff saved any catastrophes.

I was lucky that I did not see any penile prolapse in these patients, as was reported by other clinicians from the use of ACP. I did experience a goose egg-sized swelling over one jugular because of some injection of the highly irritant thiopental perivascularly. This resolved without treatment after three months without surgical intervention.

When I arrived in Norfolk in 1974, the anaesthetic agent in vogue was Large Animal Immobilon. This was a mixture of an extremely powerful morphine derivative – etorphine – and ACP. I used it in 72 patients and was fortunate that only one patient suffered from penile prolapse, which, mercifully, resolved following prompt supportive treatment using a pair of tights.

My main problems with Large Animal Immobilon were on recovery. The standard protocol was to inject an appropriate dose of Large Animal Revivon on completion of the surgery IV. I experienced one case of recycling in a pony. From then on, I used to inject an extra half of the calculated dose of Large Animal Revivon IM.

I also experienced nine cases of recycling in donkeys, so then used to inject an extra full dose of Large Animal Revivon in this species.

I was very relieved with the arrival of a protocol of IV premedication with romifidine, followed by IV ketamine. This was my preferred short‑acting general anaesthetic in 3,891 castrations.

While doing thee locum placements in Western Australia, I castrated 15 standardbred yearlings. This breed is renowned for inguinal prolapse. Australia’s equivalent of The Veterinary Defence Society will not cover practitioners who carry out an open method of castration. The protocol for anaesthesia was premedication with ACP and detomidine followed by a mixture of guaifenesin and thiopental given by flutter valve to effect.

No anaesthetic deaths occurred.

In total, 3,905 animals were castrated using a standard open technique. The vascular and non‑vascular portions were emasculated. The instrument was held in position for one minute on the vascular part.

As aforementioned, 15 animals were castrated in Australia with a semi‑closed method. Each testicle enclosed in its tunics was ligatured with a transfixing ligature before being removed with the emasculator.

The 2 mules and the first 78 donkeys were castrated using a standard open technique together with ligatures placed on the vascular and the non-vascular portions, as I had been taught at college in 1966.

I then gave a lecture in Newmarket to 58 veterinary practitioners after I had carried out 1,000 castrations. During the discussion it became evident some in the audience felt the ligatures were unnecessary. We had a show of hands, 24 practitioners did not ligature donkeys and had experienced no problems with haemorrhage.

Since that meeting, I have castrated a further 148 donkeys without using ligatures. None of these had a postoperative haemorrhage.

Owners reported seven cases of postoperative haemorrhage. Six were found not to be serious and received no further treatment.

A single case was found to be in extremis. Euthanasia was carried out. The cause of the failure of the emasculator was never found.

All the animals had an unassisted recovery from the general anaesthetic. No problems were seen.

Postoperative infection and the use of antibiotics

In total, 342 animals (8.5 per cent) were reported by the owners to have postoperative infection.

Of these, 338 were thought not to be serious. They were given five days of oral sulfadiazine and trimethoprim.

Three animals were clinically sick with a fever. These were given three days of IV penicillin and gentamicin. A single animal was found to have an infected cord. This was removed under sedation. It was given three days of IV penicillin and gentamicin, followed by five days of IV cephalosporin. All these animals then made uneventful recoveries.

The use of antibiotics at the time of surgery is controversial. Until 1998 I never gave any antibiotics. I was then persuaded by my younger colleagues to inject penicillin at the time of surgery. They could give me no evidence of their effectiveness; however, they claimed owners expected their patients to be given antibiotic cover. They also pointed out that my level of postoperative sepsis was high.

From my records, I could not see any advantage. I consider that education of clients is the most important factor.

Clients who did not bring their animals into a stable for at least 10 days on my instructions never seemed to have problems.

Although I always dressed the wounds with an oily preparation of acriflavine post‑surgery, I was never convinced of its effectiveness; however, possibly the oil helped to keep the wounds open to allow drainage. Certainly, the use of oxytetracycline spray is unlikely to be beneficial.

I think it is vital to forewarn owners swelling will occur after such radical surgery. It nearly always occurs, and in my experience it quickly lessens with time and exercise.

The use of pain relief and anti-inflammatory drugs was not considered in 1966; in the intervening years they have become the norm.

I would strongly urge clinicians to support their patients with whatever they feel is the most effective protocol. I have never used local anaesthesia; however, I think its use should be considered.

Clinicians should use their own judgement, but I do not think the use of tetanus antitoxin is required if the animal has been fully vaccinated, but is vital otherwise. It would seem prudent to start or complete tetanus vaccination at the time of surgery.

I see no problem in giving equine influenza vaccination at the same time; however, I always tried to dissuade owners from other procedures – such as foot trimming or mane pulling – as I was concerned for the anaesthetic recovery from any unnecessary delay.

I castrated a two‑year‑old Cleveland bay colt one afternoon on a paddock behind a surgery. Everything appeared to be well when the owner collected it at 5pm for the three‑mile journey home. I was called at 6am the following day – the patient had 3ft of small intestine prolapsed through the left incision. It appeared to be undamaged.

I managed to anaesthetise the horse with detomidine/ketamine. I washed the bowel in sterile saline, enlarged the incision, replaced the bowel and, with difficulty, tried as best I could to suture the inguinal ring. I then sutured the skin.

The animal recovered from the general anaesthetic and no further prolapse occurred; however, the animal died of shock at 4pm.

With the excellent assistance of a veterinary student, Jess Bartman, we gave the pony a general anaesthetic. We pulled a couple more inches of the omentum out of the wound, then removed the contaminated omentum with scissors. Jess managed to get a good mattress suture into the inguinal ring while I kept the omentum out of her way. She then sutured the skin.

The colt made an uneventful recovery with antibiotics and pain relief.

I hope this article will encourage younger equine practitioners. I only had two deaths occur following 4,000 standard castrations (0.025 per cent) – one from haemorrhage and the other, the Cleveland bay, from herniation.

I wonder if the single animal that died of haemorrhage had a clotting disorder. I would like to think so; however, I have to admit it might have been my error with the closing of the emasculator.

I have never been asked to castrate another Cleveland bay colt. I think if I was, I would use a closed or semi‑closed method.

Some drugs mentioned in this article are not licensed for veterinary use.