10 May 2021

Rob Pilsworth MA, VETMB, CERTVR, BSC(HONS), MRCVS and Derek Knottenbelt OBE, BVM&S, DVM&S, DIPECEIM, DACVIM, MRCVS discuss the establishment of this form of iodine in veterinary medicine, as well as its uses and efficacy in equids today.

In 1811 the French nation was in the midst of the intense battle campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars. The Battle of Trafalgar had passed into history, but immediately ahead lay major confrontations on many fronts, including the disastrous march on Moscow.

Vast amounts of gunpowder were required; to make gunpowder, they needed “saltpetre” (potassium nitrate), traditionally sourced by burning wood to produce ash. But wood was running out in many parts of the world, all of which had been at war now for decades.

At the same time a French scientist, Bernard Courtois, was experimenting with extracting potassium nitrate from seaweed, since a seemingly inexhaustible supply existed along the coast of Normandy. He found that when adding sulphuric acid to the ash residue left after burning dried seaweed, a strange and beautiful purple vapour was given off, which then formed a deposit of iridescent purple-black crystals on the walls of the vessel. Courtois had discovered iodine.

The first medical use of iodine occurred approximately seven years later when a Swiss doctor discovered that administration of iodine to patients with goitre was curative.

A few years later, John Davies, a surgeon working at Hertford General Infirmary in Britain, described in his textbook on surgery the use of tincture of iodine on wounds. The purpose was, in his own words, “to bring into general notice a remedy whose superior curative properties as an external application appeared to be but little known to the profession”.

Iodine was commonly used in the treatment of contaminated wounds in the American Civil War and in 1881 Robert Koch (the originator of Koch’s postulates) was among the first to confirm the antiseptic properties of an aqueous solution of iodine. For many years thereafter it became the traditional method of sterilisation of catgut suture materials.

In 1916, in the height of the First World War, a new combination of iodine was in widespread use for treatment of contaminated wounds in both horses and soldiers. Rutherford Morison named his formulation “BIPP” (bismuth iodoform paraffin paste) and was so enthusiastic of its efficacy that he claimed “in BIPP we have discovered an antidote to true sepsis”.

While BIPP is still in frequent use in some equine practices, this is usually limited to use as a cavity packing agent following drainage of “pus” from the foot in the horse. This aside, with the exception of povidone-iodine hand scrubs and the use of iodine navel dressings, routine medical uses of iodine have largely fallen out of favour. This is unfortunate since iodine exerts its lethal effect on bacteria in a way that makes it extremely unlikely that resistance will occur.

In an age of increasing incidence of multiple-resistant bacterial organisms, it is perhaps time to revisit something that was originally interpreted as a miracle cure. Can iodine in its various forms be a useful addition to our antibacterial armoury? Can we relearn from history and thereby reduce our antibiotic reliance?

The British Veterinary Codex (Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Department of Pharmaceutical Science,1965) lists several therapeutic uses of iodine in various forms, including sodium and potassium iodide administered by mouth, or in the case of sodium iodide, by IV injection to cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats and poultry. Its primary uses were listed as treatment for spasmodic asthma and catarrh due to its expectorant effects in increasing the volume of bronchial secretions.

Potassium and sodium iodides were considered to be contraindicated as an IV injection in horses, but IV sodium iodide was listed as an effective antibacterial in the treatment of actinomycosis and actinobacillosis in cattle. Historically this appears to be the only systemic use of iodine compounds as antibacterial agents.

Methods by which iodine treatment is carried out in the horse today are now listed.

Currently, no licensed injectable products containing iodine are available for use in the horse. One product – Iodure, manufactured by Vetoquinol – is commonly used under the prescription cascade system. This drug is manufactured for treatment of actinobacillosis in small ruminants and cattle.

Anyone who has worked in mixed practice will remember just how efficacious this product is, with often only one administration necessary to effect a complete cure.

When used off-licence in the horse, it is normally administered for its effect as a mucolytic agent, to help in rapid recovery from respiratory disease, especially in horses in active competition where the use of other adjunctive mucolytics may infringe anti-doping regulations.

Iodure comes in 250ml bottles, each ml containing 160mg of sodium iodide. Normally half a bottle is administered by slow IV injection every three days. This delivers approximately 20g of sodium iodide, providing an approximate peak dose of 44mg/kg to the average 450kg racehorse, at administration, which would then reduce over succeeding days.

No evidence-based study has existed to show any efficacy of this product in the horse and, following more than one experience of a horse collapsing fatally during very slow IV infusion, practitioners have been made wary of its use.

Potassium iodide can be given orally in the horse, either as a liquid solution or as a powder, given in the feed. In one large Newmarket practice (Newmarket Equine Hospital), the oral solution is made up of 750g of potassium iodide dissolved in 5 litres of water. This gives a concentration of 150mg/ml.

The conventional dose is 50ml of the solution once daily by mouth, which gives an effective dose of 16.5mg/kg once a day for a 450kg horse. The alternative is direct oral administration of potassium iodide powder (Newmarket Premixes). The recommended daily dose in this situation is 8g per horse once a day, giving an effective dosage level for the same 450kg horse of 18mg/kg, similar to that achieved with the solution regime described already.

These doses are much lower than those described for use in humans, both for treatment as an expectorant and for treatment of sporotrichosis, where doses of 4g to 6g per person per day are recommended.

Equine medicine occasionally chances on a product that is widely used before basic studies on absorption have ever taken place. One such example is creatine, which gained widespread use in the competition horse industry on the back of successful administration to both human athletes and racing pigeons as an ergogenic aid.

Only after proper scientific studies later showed that the horse, as an obligate herbivore, had no enzyme systems to break down or absorb an amino acid only found in meat did its widespread use decline.

So, is potassium iodide absorbed? The big problem with this drug is that it is freely available as a feed additive, not a medicine, and relatively inexpensive. Therefore, little drive exists for detailed clinical trials to be carried out on the drug, as the money to fund these trials is unlikely to be forthcoming. Even basic pharmacokinetic studies on blood and tissue levels have not been carried out.

Nevertheless, the British Veterinary Codex carries a good description of its pharmaceutical and chemical properties. The salt is soluble in water, alcohol and glycerine. It is reported here to be rapidly absorbed from the intestine, and excreted mainly through the kidneys into urine and into other body secretions, such as bronchial mucus, sweat and sebum. As the iodine is included into mucus, sebum and sweat, water is taken with it and this probably accounts for its expectorant properties.

However, in addition it seems the low concentration of iodine also has a usable antibacterial property, which has been anecdotally reported for many years. Of course, this same property is said to be the reason for its particular efficacy against Actinobacillus lignieresii, the cause of wooden tongue in cattle, and actinomycosis, the cause of “lumpy jaw” in cattle. This then may account for its anecdotal antibacterial effects on skin and airway infections.

For the clinician, the reassuring aspect of the use of potassium iodide is the ability of this drug to produce profuse thick bilateral conjunctivitis after only a few days of admission in many horses. The likelihood is that the early signs of iodism resulting from high systemic concentrations results in nasal and ocular discharges, a soft productive cough and a scurfy skin. This, at least, indicates that the drug is gaining access to the circulatory system and is being delivered to the precorneal tear film.

It is likely that the sticky nature of this discharge from the nose and the eyes is due to bacterial death within the conjunctival sac and airway, respectively. This reaction appears to be harmless and rapidly disappears following withdrawal of the potassium iodide for 24 hours since excretion is very effective. Recurrence is seemingly rare if potassium iodide re-administration begins after this withdrawal period, but dosage should then be limited to 8g every 48 hours, rather than daily.

Probably the most common indications for iodide-based treatments are in one of the following four categories:

Frustratingly, no evidence-based studies further explore the efficacy of these agents in any of these situations. One of the authors (Rob Pilsworth) began to use potassium iodide after it was suggested by his immediate superior, Raymond Hopes, as an adjunctive treatment for treatment of post-castration infection/seroma (Figure 1).

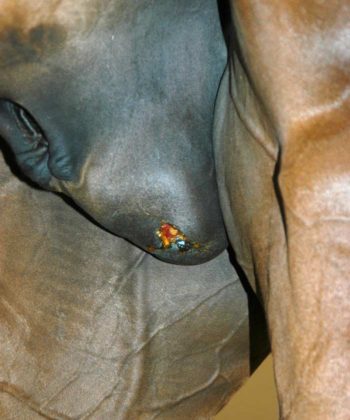

As a relatively new member of the large Rossdales practice in Newmarket, Rob was keen to avoid subsequent problems following castration. After asking Raymond’s advice, following one intractable case that ended up at surgery eventually with a “scirrhous” cord (Figure 2), he began to use potassium iodide on a routine basis for any horse that subsequently developed a seroma or infection requiring further treatment.

He was pleasantly surprised by the fact that adding this to his normal practice of reopening the seroma, flushing out the cavity and administration of parenteral antibiotics resulted in very rare recurrence, which was in contrast to his previous experience.

In 40 years of practice he never had another case of scirrhous cord. Several eminent equine clinicians in Newmarket don’t wait for the complication, but give a course of 10 days of potassium iodide following all open castrations as a routine prophylactic measure.

Everyone hates anecdotal evidence. Nonetheless, and on the basis that two anecdotes don’t make evidence, one author (Dr Pilsworth) carried out a limited unpublished study to explore use of potassium iodide in the management of post-castration infection.

Part way through this study the double blinding was withdrawn since two cases of recurrence had occurred following treatment. Release of the blinding data showed that both cases had been in the placebo group. The study had to be closed at that time so further information was not obtained. This illustrates the difficulty of gaining sufficient evidence of efficacy from clinical practice where placebo use is not ethically justifiable.

To the clinician, current cost of a bottle of Iodure containing two treatments for a horse is approximately £37. As the drug is intensely irritant perivascularly, it is normally administered with an infusion set and catheter, adding approximately £8 per horse, so overall approximately £26 per horse for consumables and any additional professional fee for administration.

This would normally be repeated after three days, so for a one-week course of treatment £52 for consumables, and two injection charges and visit costs. Realistically this will approximate to a total cost of at least £100.

The most readily available form of potassium iodide to UK practitioners is as a powder or larger crystals, produced as a food supplement (Newmarket Premixes, Sudbury). Cost to the practitioner is £60 per 750g tub, (8p/g). The normal daily dose of 8g for a 450kg racehorse therefore equates to 64p/day. A one‑week course would, therefore, work out at £4.48, plus any dispensing fee and mark-up.

Perhaps one of the schools of veterinary medicine could be induced to carry out some very basic research on this old remedy, still trusted by many to be effective. With the day looming in which antibiotics may no longer be efficacious, it is knowledge we may one day be extremely grateful to have.