21 Oct 2019

Karin Kruger shares some of the techniques and drugs she has found helpful when sedating and anaesthetising horses.

No one right answer exists to the question of how to sedate a horse, but this article will share some of the techniques and drugs the author finds helpful in various circumstances.

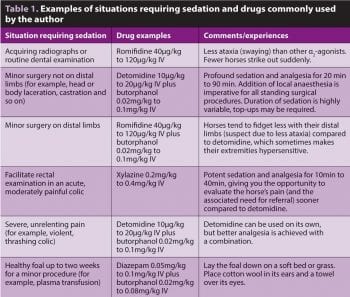

The most commonly used sedatives in horses for short-term sedation are the α2-adrenergic agonists, either alone or in combination with opioids. Acepromazine (ACP) can also be used alone to achieve mild to moderate sedation, or in combination with other sedatives. Due to differences in depth of sedation, peripheral sensitisation and ataxia, the author’s preference changes depending on the circumstance (Table 1).

The majority of handled horses will tolerate the IV injection of medications, which is done predominantly in the jugular vein using a 20g (yellow) hypodermic needle. Injection of sedative drugs into the cephalic vein using a 23g (blue) needle is a useful alternative in jumpy foals when the handler is battling to hold it still.

Spending a few extra minutes to desensitise and teach a foal or fearful horse to accept injections will stand both the horse and the veterinarian in good stead for many future interactions.

The skin overlying the intended injection site can be desensitised by firm pinching while holding the needle and syringe in the other hand (Figure 1). This can be done several times while praising the horse and feeding it treats until it relaxes when the veterinarian approaches the neck with a needle.

By using a new needle (not the one just used to draw up the drug), tissue drag and associated discomfort are minimised. The handler can also be asked to use a flat hand positioned caudal to the eye to obscure the horse’s peripheral vision on the side of the intended injection (Figure 2).

In poorly trained or needle-shy horses where IV injection poses a risk to handlers, sedation can be achieved using oral detomidine paste administered sublingually. It takes approximately 40 minutes to reach maximal sedation, which in some instances may be profound enough to facilitate handling or minor procedures (for example, dental examination).

Oral ACP is also useful to facilitate mild to moderate sedation, and administration well in advance of a procedure can be particularly helpful in dealing with healthy young or fractious horses (for example, colts for castration).

Some horses that do not tolerate jugular injection may be more amenable to IM injection. Although none are licensed for IM use, all commonly used α2-adrenergic agonists and opioids have good bioavailability after IM injection, but require higher dosages and a longer time to reach maximal effect.

An extension set attached to a needle, which is pre-loaded with sedative drugs, can be used to allow the injector to step away from the horse immediately after placing it in a muscle.

Horses that cannot be safely handled at all can be injected with a pole syringe if appropriate infrastructure is available to adequately separate the horse from the injector (for example, chute), or the horse can be darted by a professional. Veterinarians should never compromise their own safety or that of their team.

Field anaesthesia can be appropriate for healthy horses where a minimal likelihood of complications exists or in selected emergencies. Always consider whether transporting a horse to an equine hospital or standing sedation is more appropriate. Where possible, a complete physical examination, with particular attention to the cardiac and respiratory systems, is imperative in establishing whether a horse is a good candidate for field anaesthesia.

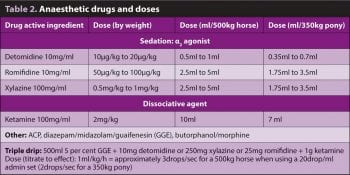

The most widely used protocol for equine field anaesthesia comprises of heavy sedation with an α2-adrenergic agonist, followed by ketamine induction and maintenance with a triple drip. To improve muscle relaxation and smooth induction, diazepam/midazolam or guaifenesin may be added for induction.

Depending on the type of procedure and patient requirements, further sedation (for example, ACP), analgesia (for example, butorphanol or morphine), anti-inflammatories (for example, flunixin meglumine), appropriate antibiotics and a tetanus booster should be considered (Coumbe, 2013).

For optimal safety, the horse should be as relaxed as possible prior to induction. If time allows, ACP and anti-inflammatories may be given several hours prior to anaesthesia. By sedating the horse well in advance of any potentially stressful handling, lower doses of drugs will be needed and induction tends to be much smoother.

Although not always possible, appropriate antibiotics should ideally be given so adequate tissue levels are reached at the time of incision. For IM penicillin, aiming for four hours prior to incision would be ideal (Ensink et al, 1996). IV antibiotics can be given shortly before induction.

Each horse’s weight can be estimated as accurately as possible and drug doses calculated: bodyweight (kg) = (heart girth[cm]2) × length/10312.5; length = point of shoulder to point of the hip.

The key to a safe anaesthetic lies in planning and preparation. The following are a few planning tips to ensure the procedure is as safe and stress-free as possible:

The horse should be sedated with an α2 agonist and an opioid given at the same time (Table 2). For healthy horses undergoing short elective procedures, the author prefers romifidine for pre-anaesthetic sedation, as it causes less ataxia during recovery. Wait at least five minutes for drugs to reach maximal effect.

In anxious horses, you may need to increase the dose of α2 agonist. The author considers a horse adequately sedated for induction if she can stick her finger in its ear without eliciting a reaction.

Once the horse is deeply sedated, ketamine is injected as a fast bolus. The anaesthetist maintains control of the horse’s head and pushes the shoulder away as the horse starts to go down. The horse may take up to 60 seconds (rarely even 120 seconds) to go down after ketamine injection. Should you decide to use diazepam or midazolam, this should be given immediately prior to, or together with, ketamine.

To minimise the risk of myopathy and neuropathy, care should be taken with the positioning of patients. In lateral recumbency, the dependent forelimb should be pulled as far forward and dorsal as possible to decrease pressure on the radial nerve and triceps muscle, with the upper limbs supported in an anatomic position.

Headcollars should be soft, padded, smooth and not tight to prevent damage to the facial nerve, or can be removed. The lower eye should be protected.

After heavy sedation and induction with an α2 agonist and ketamine, most horses will sleep for 15 minutes to 20 minutes (depending on the horse and the procedure). Local anaesthesia, analgesia and anti-inflammatories will help to extend the duration of anaesthesia.

For an additional 10 minutes to 15 minutes of anaesthesia, top up with one-third to half the ketamine dose, preferably before the anaesthetic plane becomes too light. For longer procedures (up to an hour), a triple drip is more appropriate. The longer the anaesthetic, the higher the risk of drug accumulation and a poor recovery.

The person fulfilling the role of the anaesthetist should be able to answer the following questions at all times:

This may seem rather obvious, but not paying attention even for a short time could have catastrophic consequences. Remember to monitor A (airway), B (breathing) and C (circulation). An anaesthetised horse should take at least six to eight deep breaths per minute. Pulse quality and capillary refill time will provide valuable information about the adequacy of circulation. Heart rate is not correlated to the depth of anaesthesia.

Signs that the anaesthetic plane is too light include an increased rate and depth of respiration, fast palpebral reflex, nystagmus, swallowing and movement. Rapid shallow breathing, apnoea, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, weak pulses, absent palpebral and corneal reflexes, and a central globe are signs that the anaesthetic plane is too deep.

If multiple top-up doses of ketamine were given, sedation for recovery is highly recommended. Administering a small dose of romifidine as soon as the horse starts to move generally smooths recovery. The horse should not be stimulated to get up too soon. You can decrease sound with cotton wool and earmuffs, and cover the horse’s eyes with a towel or drape to decrease light stimulation.

Ensure the horse has adequate analgesia on board. With the right technique, even large horses can usually be held down for their first two to three attempts to stand, which will make subsequent standing attempts much more coordinated (Figure 3). Depending on the skill of the handlers, head and tail ropes may assist the horse with recovery. Untrained owners and onlookers should not be anywhere near a recovering horse to prevent injury.

In summary, whether sedation or anaesthesia is the end goal, thoughtful planning with due consideration of the temperament and training of the patient, the skill of the handlers and the work environment will go a long way to ensure a smooth, safe procedure.