6 Mar 2017

Claire Wylie reviews peer-reviewed studies regarding diagnosis, treatment and prevention published in 2016.

Figure 4. Research is exploring the use of novel drugs, digital hypothermia and gene therapy as potential mechanisms to prevent failure of the dermal/epidermal joint progressing to catastrophic loss of support for the distal phalanx. Image: Simon Collins

Laminitis remains a threat to all equidae. This article reviews peer-reviewed studies regarding diagnosis, treatment and prevention published in 2016. Two studies improved the diagnosis evidence base. The first identified the key clinical signs differentiating laminitics and non-laminitics as bilateral forelimb lameness, increased digital pulses and a flat/convex sole. However, it found the classic “laminitis stance” was present in fewer than half of laminitis cases. The second supported further investigation into the Horse Grimace Scale as a tool for quantifying pain severity, with the advantage of not requiring locomotion. The treatment of laminitis has been controversial, with provision of pain relief remaining a considerable challenge.

Recent studies have found tramadol and the soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor t-TUCB show promise as new tools within the multi-modal approach to analgesia. In-depth study of chemokine receptor antagonists and gene therapy to mitigate lamellar damage was justified. Further exploration of the benefits of hypothermia identified ice water immersion of the foot and a portion of the distal limb and a prototype portable dry sleeve were the most effective.

Finally, four studies improved the epidemiological knowledge base for the disease. Collaborative research will continue to refresh the latest thinking until laminitis is a disease of the past.

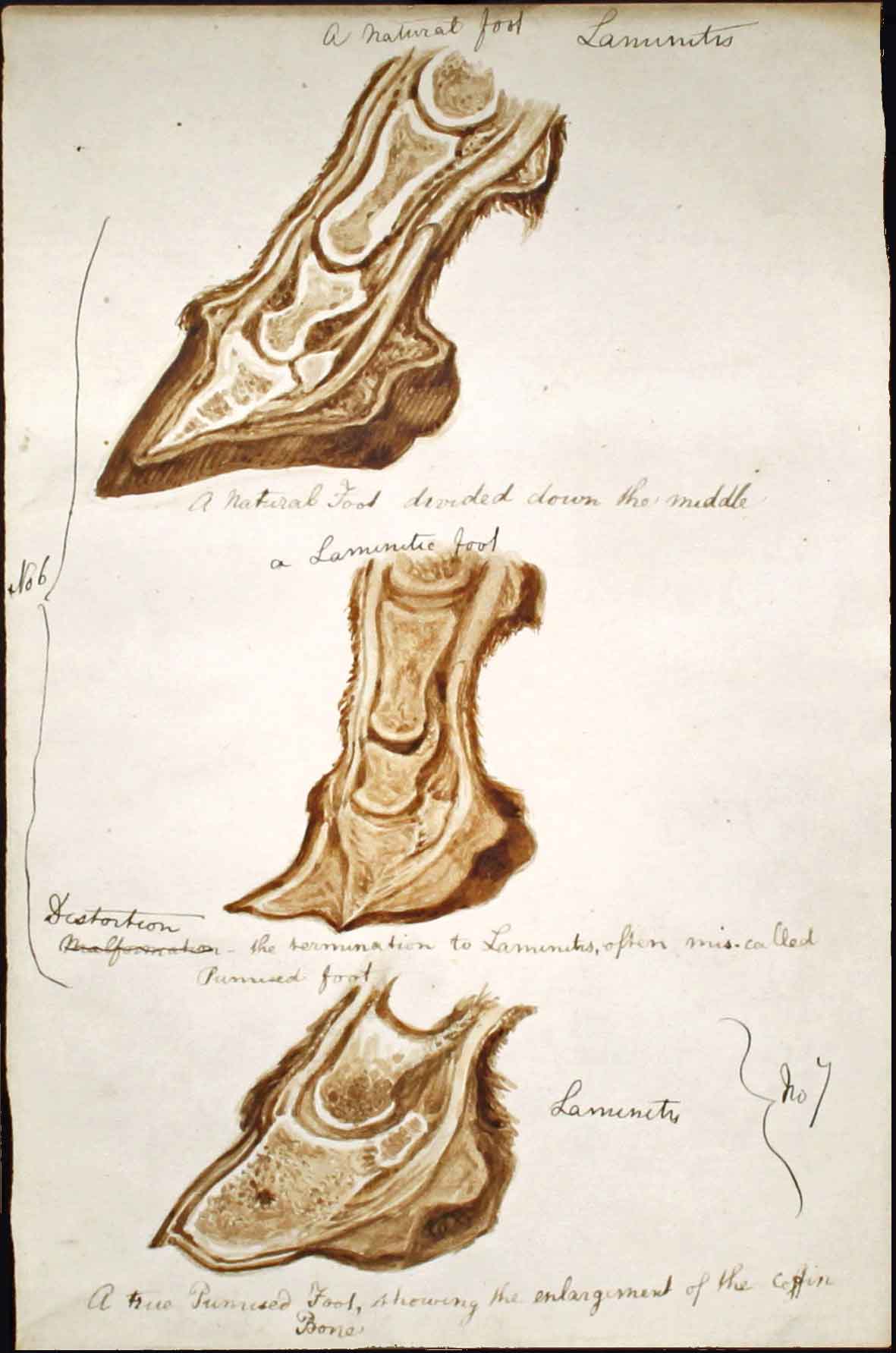

Laminitis is nothing new. Examination of equine fossil specimens in the US suggested around 75% displayed evidence of chronic laminitis and the disease has been well recorded historically (Figure 1).

However, laminitis continues to threaten the welfare of all horses and ponies and has profound humane, economic and emotional effects on all involved. This article reviews the latest peer-reviewed primary studies on the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of equine laminitis.

Despite the perceived importance of laminitis, remarkably few evidence-based studies have been conducted regarding its clinical presentation and strategies for effective diagnosis. Gone are the days when laminitis was considered easy to diagnose.

Research into laminitis pathophysiology has highlighted the complexities of the underlying disease processes and it has been increasingly recognised clinical presentations will be variable depending on such aetiology, disease stage, number of feet involved and concurrent diseases. Two studies published in 2016 have addressed the diagnosis of laminitis.

The first study evaluated the potential for veterinary-recognised clinical signs to discriminate an active episode of acute or chronic laminitis from other causes of lameness1. The prevalence of each clinical sign was compared between 588 horses diagnosed with laminitis and 201 horses diagnosed with non-laminitic lameness.

“Bilateral forelimb lameness” was the best discriminator, such that 92% of horses with this clinical sign had laminitis, while the additional presence of “increased digital pulses” improved this to 99%.

Presence of a flat/convex sole also significantly supported discrimination between laminitics and non-laminitics. However, the difficulties in accurately diagnosing laminitis in the field were highlighted. No clinical signs were present in every case, and notably “front feet in front of the body” (representing the classic “laminitis stance”) was found in fewer than half of the diagnosed laminitis cases, and did not prove to be a useful discriminator (Figure 2).

The appropriate reluctance of vets to trot suspect laminitis cases on welfare grounds hampered the assessment of some clinical signs and precluded classification on the basis of the classic severity scoring system proposed by Obel2.

A potential alternative approach to quantifying the severity of pain associated with laminitis was described by the other paper regarding laminitis diagnosis3.

This study investigated a way to describe acute laminitis pain severity at rest, without requiring any forced locomotion, on the basis of the recently developed Horse Grimace Scale (HGS). This is a method of coding facial expressions on the basis of a three-point score for six different units: “stiffly backwards ears”, “orbital tightening”, “tension above the eye area”, “prominent strained chewing muscles”, “mouth strained and pronounced chin”, and “strained nostrils and flattening of the profile” (Figure 3).

Ten acutely laminitic horses were examined before, and seven days after, routine, standardised treatment. For both time points, three levels of assessment were used: in the first, one vet provided an Obel score after watching the horses walk and trot; in the second, two still images were reviewed by four vets to provide the HGS score and a subjective assessment of the intensity of pain, from 0 (no pain) to 3 (severe) was made, and in the third a 15-second video clip was reviewed by two vets to provide another HGS score.

The authors reported the HGS was a potentially effective method of assessing pain in acute laminitic horses at rest. Horses with higher HGS scores received higher Obel scores and were subjectively classified as more severely painful.

Higher HGS scores were also given to horses prior to treatment compared to seven days later. Interestingly, the authors reported the video clips appeared more difficult to score than the still images, suggesting potential challenges in implementing the HGS for diagnosis of laminitis in clinical settings.

Effective diagnosis of early-stage laminitis is challenging and further work to elucidate and highlight the difficulties is required to enable recognition of all the permutations of laminitis. This is crucial as early diagnosis facilitates timely palliative and therapeutic treatments to maximise recovery prospects.

Over time, the treatment of laminitis has been controversial. Many strategies fall in and out of favour, resulting in regular changes to treatment approaches. One of the main priorities in laminitis treatment is pain relief. However, with inflammatory cytokine and neuropathic pain pathways, treatment remains complex and, to date, none has proven to provide effective analgesia in all cases.

Two studies regarding analgesia were published in 2016 and, while they were limited with regards to study design and size, they present promising new approaches to the difficulties surrounding pain management. Further work may result in these drugs being recommended for use in general practice in the future.

Tramadol has been identified as a potentially attractive analgesic due to its multimodal mechanisms of action and one study quantified its effect in four horses with chronic laminitis4. Tramadol was given orally for 7 days every 12 hours at both 5mg/kg bw and 10mg/kg bw doses. Before and during the treatment, physiological variables (arterial blood pressure, heart and respiratory rates and intestinal sound scores) were measured and the analgesic effect was quantified as an “off-loading frequency” via a force-plate system.

Off-loading frequencies are defined as a proportion of weight withdrawal from the limb relative to its mean load over time and are increasingly being used as a method of assessing pain – with laminitic horses displaying an off-loading frequency between 4 and 10 times greater than non-laminitics. The 5mg/kg dose did not appear effective, with no significant change in off-loading frequency observed (9% reduction). However, the 10mg/kg dose showed promise, with the off-loading frequency significantly decreasing by an average of 40%.

Disappointingly, analgesia was not complete, suggesting tramadol is unlikely to be the analgesic panacea. None of the physiological variables changed significantly with either 5mg/kg or 10mg/kg treatment. However, concerns remain even greater concentrations may lead to adverse gastrointestinal effects, with transient colic signs reported at the 10mg/kg dose. While further work needs to be done to assess its safety, tramadol may, at least, prove to be another component of the multimodal approach to laminitic analgesia.

Another novel approach to pain management is the pharmacologic inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase, implicated as a component of both inflammatory and neuropathic pain.

One study investigated the efficacy of a soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor t-TUCB once a day for 1 to 10 days at 0.1mg/kg bw as adjunct analgesic therapy to 10 chronically laminitic horses refractory to pain management and/or for which euthanasia was being considered5. The t-TUCB was found to significantly reduce the frequency of forelimb lifts measured over a five-minute period by 36%, and the pain score as assessed by two vets and/or vet technicians using a visual analogue scale, from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), by 18%.

No significant changes were found in the physiological variables (heart and respiratory rates, mean arterial pressure or gastrointestinal sound score). However, as with tramadol, not all horses experienced complete pain relief, despite t-TUCB being given in combination with other varying medications. Current research efforts are refining the therapeutic approach.

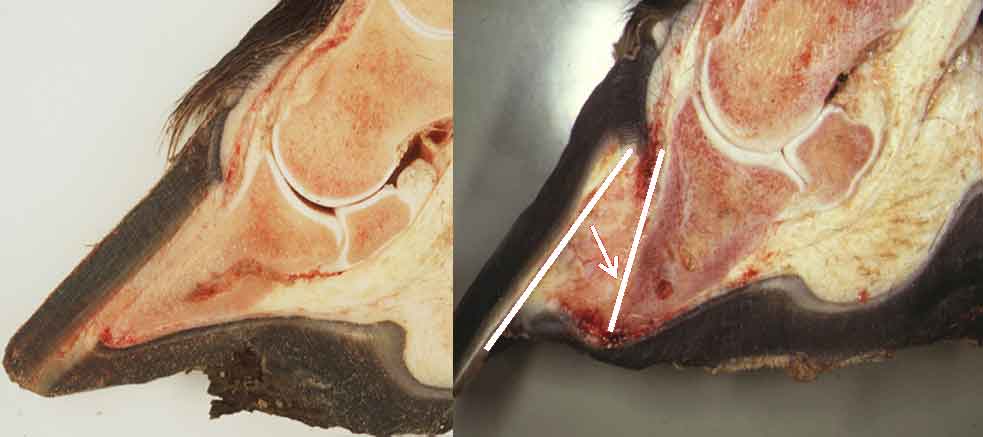

Another major challenge in laminitis treatment is the prevention of disease progression and three studies have explored novel approaches to possible treatment and prevention.

One of the practical challenges in effective treatment is targeting the lamellae encased deep within the equine foot. One study reported on efforts to develop a method to deliver therapeutic proteins on the basis of “gene therapy” – using a virus as a vehicle to insert a therapeutic gene efficiently within inaccessible tissue6.

Three vector serotypes of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors (rAAV2/1, 2/8 and 2/9) successfully transduced equine foot tissues in seven horses. The addition of surfactant-containing saline significantly increased transduction. This work marks a positive start to the authors’ long-term goal of providing a practical clinical therapy. Future work will aim to improve the technique in the standing horse and evaluate therapeutic proteins that could block the enzymatic degradation of dermal:epidermal interface.

The initial event triggering failure of the dermal-epidermal junction has yet to be elucidated (Figure 4). However, evidence exists of considerable leukocyte involvement and neutrophil infiltration. CXCR1 and CXCR2 are two G-protein receptors with a high affinity for chemokines previously detected in other neutrophil-associated equine conditions.

One study investigated the effect of treatment with the CXCR1/2 antagonist DF1681B every six hours in a 24-hour period in six horses with oligofructose-induced laminitis compared to six untreated controls7. A significant increase in the mean score of histological lamellar degradation was found from baseline to 12 and 36 hours post-laminitis induction in the untreated group, yet no significant increase was found in the treated group.

These preliminary findings have suggested the CXCR1/2 antagonist DF1681B may play a role in the mitigation of inflammatory lamellar damage and dermal-epidermal junction damage. Further study is required to clarify any therapeutic benefits.

The benefits of prophylactic digital hypothermia have been recognised in experimental models and clinical studies. More recently, evidence is available of prevention of lamellar failure, even when applied after the onset of laminitis-associated lameness, suggesting a therapeutic role.

It is recommended at-risk horses maintain a hoof wall surface temperature of 5°C to 10°C for 48 to 72 hours; however, the practical challenges of such an intervention in the equine patient are considerable8.

Further work has been published comparing seven methods of providing continuous therapeutic cooling of the equine digit in clinical practice9. Using four horses, they found the two ice water immersion methods that included the foot and a portion of the distal limb – a wader-style boot or a repurposed 5L fluid bag with the top cut off secured to the limb with adhesive tape and a prototype portable dry-sleeve cooling device – were capable of sustaining the hoof wall surface temperature lower than 10°C for an eight-hour period.

These methods should act as the basis for further studies validating the optimum systems and generating protocols clinicians can adopt to prevent and/or treat laminitis.

While these novel therapeutic approaches justify further work, as with any disease the holy grail for laminitis research remains its total prevention. Determination of risk factors using epidemiological techniques is key and four such studies have been published in 2016 (Table 1). Agreement between studies existed for an increased risk of laminitis with increased serum insulin, a diagnosis of equine metabolic syndrome and for pony breeds. The studies also agreed no evidence was seen that prednisolone was a risk factor for initial laminitis episodes, although one study found an association with subsequent laminitis episodes. Further work to explore whether identified modifiable risk factors have a causal relationship with laminitis may help us reduce the impact of the disease in the future.

Laminitis may be nothing new, but it is encouraging scientists, epidemiologists, veterinarians, farriers and horse owners are continuing to research new avenues regarding its diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Collaborative research will continue to refresh the latest thinking until the goal to make laminitis a disease of the past is realised.