15 Jan 2018

Philip Ivens discusses this common eye disease in horses, highlighting its subclinical insidious form and how to identify it.

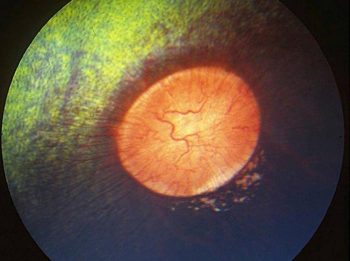

Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU) – also known as moon blindness, iridocyclitis and periodic ophthalmia – is the most common cause of blindness in horses globally.

ERU is characterised by repeated episodes of intraocular inflammation that develops weeks to months after an initial uveitis episode subsides. Not every case of initial equine uveitis will develop into ERU, but each horse that has signs consistent with uveitis is considered at risk of reoccurrence until several years without relapse have passed.

This article will focus on cases of subclinical uveitis where the initial uveitic episodes and subsequent episodes of intraocular inflammation are often subclinical and/or go undetected by the equid’s carer.

The uveal tract embryologically derives from the middle vascular component of the eye (mesoderm) between the outer layer (cornea and sclera; ectoderm) and the inner layer of the eye (retina and corneal endothelium/Descemet’s membrane – endoderm). The uvea can be divided into anterior and posterior components.

The anterior component consists of blood vessels within their connective tissue lined by a double layer of epithelium, including the iris and ciliary body.

The posterior component consists of primary vascular supply of the horse retina between the retina and sclera, containing the choroid, which is divided into dorsal and ventral regions:

Choroidal vasculature is not usually observed, but may become visible – especially with tapetal hypoplasia and ocular albinism.

The uveal tract contains most of the blood supply of the eye and is in direct contact with the peripheral vasculature.

A barrier exists between this blood circulation and internal aspects of the eye, called the blood-ocular barrier (the tight junctions between the non-pigmented epithelial cells of the ciliary body and non-fenestrated iridial blood vessels) and the blood-retinal barrier (tight junctions between the cells of the retinal pigmented epithelium and non-fenestrated retinal vessels).

In cases of trauma or inflammation, these barriers can be disrupted, allowing blood products and cells to enter the eye. This disruption enables activation of host immune responses, including production of antibodies to self-antigens not normally recognised by the horse’s own immune system, as well as production of antibodies to foreign antigens inside the eye.

ERU can be classified a number of different ways (Table 1), which can be helpful clinically. The focus of this article is to highlight the importance of the subclinical insidious form of the disease.

Most clinicians are well-versed in the presenting signs of classic acute inflammatory episodes, presenting with ocular pain, miosis, epiphora and blepharospasm. Periocular swelling, corneal oedema and aqueous flare may be present, and the iris may be dull. Mottled pigmentation and hyperaemia may also be seen.

Insidious ERU is characterised by a low-grade, intraocular inflammation that does not manifest as outwardly painful episodes.

Internal ocular inflammation persists and leads to degeneration of ocular structures and chronic sequela of ERU. These cases, in the author’s opinion, are harder to recognise and often found at routine ocular examination, as part of pre-purchase examination (PPE), for example.

When examining an eye and an abnormality – for example, a cataract – is seen, it is imperative for the clinician to see if evidence of other signs/sequela of ocular inflammation is present, which would point to ERU being a possible aetiology. Appaloosa and draft horses are thought to be more commonly effected by this type of uveitis.

It is beyond the scope of this article to talk about each diagnostic step in detail. It is assumed a good working knowledge of these diagnostic steps exists, and only tips and tricks for adding evidence or highlighting a possibility of insidious ERU will be described.

Optimising our indicators of disease is key and then knowing when to refer for a more specialist opinion is important so we reduce the clinical horizon for this disease.

Any history of repeated eye problems should raise alarm bells. Particularly common, in this author’s experience, is the horse that has repeat bouts of conjunctivitis, which is commonly blamed on the flies in the summertime.

Looking at the patient and observing eyelid angle (decreased/down) for mild blepharospasm from front on to the horse can be helpful. Observing any signs of chronic epiphora, such as areas of alopecia below the medial canthus or depigmentation in that area, can be helpful.

Having a quiet dark room can be a challenge on some yards and, if the author is struggling to get that environment, it is suggested the horse is brought to the clinic as for other ailments – lameness, for example.

Examining the eye before and after mydriasis is important – one per cent tropicamide is recommended to achieve diagnostic mydriasis; not atropine, which can cause mydriasis in the healthy eye for an extended period of time.

Examining the patient in a controlled and restrained manner is really helpful. Stocks can be helpful in this regard, as can chemical restraint (for example, detomidine and butorphanol IV), with the patient’s head being placed on a head stand to keep it still, so the clinician can focus on individual anatomic regions, without the patient moving.

Transilluminating the anterior structures using the light of the direct ophthalmoscope (this can also be achieved with a transilluminator and pen torch/mobile phone torch) without looking down the ophthalmoscope, using different angles of both light and observer, can highlight subtle cornea hazing, for example, or an atrophied corpora nigra.

Distant ophthalmoscopy – where retroillumination of vitreous, lens and aqueous can be achieved by holding the direct ophthalmoscope at arm’s length – can be really helpful in identifying opacities (such as cataracts) or changes in colour or turbidity of the humours.

The author prefers the technique of focusing on the retina first (after transillumination of the adnexa and anterior segment, and retroillumination have been completed) and using the positive dioptres to move through the vitreous, posterior lens capsule, lens cortex, anterior lens capsule and finishing on the iris, while the observer stays the same distance away from the object – in this case, the patient’s eye.

Slit lamp microscopy (Figure 4) improves visualisation and localisation of even slight lesions of the cornea, anterior chamber, lens and anterior vitreous. It can also be used to assess corneal thickness, anterior chamber depth and aqueous flare. The author recommends use where nothing is found with direct ophthalmoscopy and/or it is unclear what and where the observed lesion is.

Indirect ophthalmoscopy (Figure 5) involves using a handheld converging lens near the patient and a light source near the examiner’s eye.

A larger area of ocular fundus can be visualised at any one point in time, with indirect versus direct ophthalmoscopy. This may allow the examiner to detect disease more easily.

Anaesthetising the cornea with topical tetracaine with or without an auriculopalpebral nerve block will greatly facilitate getting reliable measurements. Normal IOP is 15mmHg to 30mmHg, with IOP of the right and left eye of the given horse being within 5mmHg to 8mmHg.

Most eyes with acute uveitis are hypotensive and the anterior chambers are shallow, with a tonometry of 5mmHg to 12mmHg. Some classic cases that have had numerous reoccurrences and insidious cases may develop secondary glaucoma (greater than 30mmHg to 35mmHg). However, many cases of insidious ERU have normal IOP, even on repeat measurement over different time periods. A normal IOP does not rule out insidious ERU.

Insidious ERU can be easy to miss and vary from a subtle hint of ocular disease of the uvea and associated structures, to the dramatic sequela in horses that “have never had any eye problems” picked up at routine examinations, such as PPE.

Thorough examination will greatly aid diagnosis and referral to a specialist will help in some circumstances, even to further document more subtle signs and join the dots together to get a firmer diagnosis and prognosis.