8 Jul 2019

Laura Quiney and Sue Dyson take a look at the latest clinical research concerning this prevalent condition in horses.

Image: © yo camon / Adobe Stock

Laminitis is a common and debilitating condition that can result in recurrent lameness or euthanasia (Luthersson et al, 2017).

Research over the past decade has led to a complete rethink on the cause of laminitis, which is now considered to be a syndrome in association with systemic disease, rather than a primary disease entity (with the exception of supporting limb laminitis as a result of altered weightbearing; Patterson-Kane et al, 2018).

Improved understanding of the underlying causes has precipitated significant developments in the diagnosis and management of laminitis. It has also provided important insight into how laminitis may be prevented.

Laminitis episodes are often recurrent, and the outcome is often unpredictable and can cause irreversible changes within the foot. Therefore, prevention is key to improving the welfare of equids. The aim of this article is to present the latest clinically relevant research with regard to the diagnosis and prevention of laminitis.

While no truly pathognomonic clinical signs associated with laminitis exist (Wylie et al, 2013), diagnosis of acute or chronic laminitis is straightforward in many cases. Typical clinical signs include lameness involving one to four limbs, reluctance to move, lameness exacerbated by turning, weight shifting, weightbearing preferentially through the heels (a so-called “laminitis stance”), increased amplitude of digital pulses and a painful response to the application of hoof testers at the toe (Dyson, 2011). However, no one clinical sign is present in every case and the classic “laminitis stance” has been shown not to be a useful discriminator (Wylie et al, 2016).

Owners with prior experience of the disease were usually quite good at correctly suspecting laminitis. However, 45% of owners did not recognise the clinical signs of laminitis, which was later diagnosed by their vet (Pollard et al, 2017).

Subclinical laminitis may be underdiagnosed compared with the more well-recognised form of acute-onset of clinical signs. Subclinical laminitis is typically insidious in onset and can contribute to poor performance, bilaterally shortened forelimb step length or loss of extravagance of forelimb movement. It is thought that unrecognised subclinical laminitis may precede apparent acute-onset laminitis (Tadros et al, 2019).

One group showed advanced histological lesions may be present in horses with reportedly recent acute-onset endocrinopathic laminitis, indicating pre-existing pathology (Karikoski et al, 2015; 2016). Radiological changes associated with the distal phalanx or hoof wall have been reported in horses with subclinical laminitis (Linford et al, 1993).

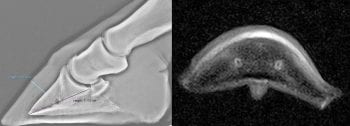

Mullard et al (2018) retrospectively reviewed the lateromedial radiographs of 415 feet of 279 horses with foot pain, but without any history or clinical signs of acute laminitis.

The ratio between the thickness of the dorsal hoof wall (hoof wall to distal phalanx distance; HDPD) and the palmar length of the distal phalanx (HDPD ratio) was reported to be 0.25, standard deviation 0.03 (range 0.19 to 0.36; median 0.25; interquartile range 0.23 to 0.26). Horse age, breed and height to bodyweight ratio had a significant effect on HDPD ratio in the final multivariable model; however, these only accounted for 8.4% of HDPD ratio variability.

A significant association existed between HDPD ratios of greater than 0.25 and new bone formation on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx (p=0.01). New bone formation may reflect increased or abnormal stress on the suspensory apparatus (including the lamellae) of the distal phalanx.

A trend (p=0.07) existed between HDPD ratios greater than 0.25 and modelling of the toe of the distal phalanx (so-called “slipper formation”), which is associated with chronic laminitis.

This study has indicated high HDPD ratios may reflect subclinical laminitis or laminar pathology.

The authors have observed horses with acute laminitis sometimes have high HDPD ratios without or preceding distal phalanx rotation and/or distal sinking (Figure 1).

High HDPD ratios appear to be a potential prodromal radiological sign of acute laminitis; however, further comparative and longitudinal studies are required to determine the association.

The management of laminitis can be challenging and disease progression can be unpredictable. Disease prevention is, therefore, the ultimate aim.

Epidemiological methods have been used to identify modifiable causes and risk factors for disease. Endocrinopathic laminitis is associated with insulin dysregulation and accounts for more than 90% of laminitis cases (Karikoski et al, 2011).

Although the relationship between hyperinsulinaemia and the development of laminitis has been confirmed in both clinical and experimental studies, the mechanism of action has not yet been determined (Durham et al, 2019).

Serum insulin concentrations are positively correlated with the Obel grade of laminitis (de Laat et al, 2019). Equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) are the two most common laminitis-associated endocrinopathies (Ireland et al, 2018; Durham et al, 2019). Menzies-Gow et al (2017) performed a prospective cohort study in which risk factors for the development of laminitis were assessed in a group of 446 horses without a previous history of the condition.

Physical observations and biochemical values were acquired at the start of the study, and the horses were followed over three years. Obesity was common (72.2%); however, in the final multivariable model, this was, surprisingly, not a risk factor for the development of laminitis.

Risk factors included low plasma adiponectin, high basal insulin and high post-dexamethasone insulin levels. Further prospective studies would be necessary to determine the fluctuation and inter-relationship of these biochemical markers prior to a laminitis episode.

It is now clear normalisation of hyperinsulinaemia through the successful management of underlying endocrinopathies is central to the prevention of laminitis. For both EMS and PPID, early detection and management prior to the development of subclinical laminitis – and especially acute laminitis – is essential to prevent permanent architectural alterations to the suspensory apparatus of the distal phalanx.

EMS appears to occur as a result of the interaction between both genetic and environmental factors (McCue et al, 2015).

It is recognised horses with EMS have a typical phenotype and are commonly described as “good-doers”. Two genome-wide association studies have identified a risk locus associated with EMS in Arabian and Welsh ponies (Lewis et al, 2017; Norton et al, 2017). Obesity and intake of highly glycaemic foodstuffs, such as non-structural carbohydrates, are believed to contribute to, or exacerbate, insulin dysregulation (Bamford et al, 2016; Coleman et al, 2018). Inactivity may also play a role (Liburt et al, 2011).

Weight loss through dietary modification has been shown to mitigate hyperinsulinaemia in horses with EMS (Van Weyenberg et al, 2008).

Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for managing and monitoring insulin dysregulation in horses with EMS have been published (Durham et al, 2019). Metformin hydrochloride is a pharmacological aid used for insulin dysregulation in horses (off-licence) and humans. However, its clinical efficacy is debatable. One study demonstrated decreased basal serum insulin concentrations over time in horses administered 15mg/kg metformin hydrochloride orally twice daily (Durham et al, 2008). However, a more recent study demonstrated no effect on insulin regulation (Tinworth et al, 2012).

The bioavailability of metformin hydrochloride in horses is poor (Hustace et al, 2009). Metformin hydrochloride may decrease glucose absorption via a direct effect on enterocytes, which may explain altered postprandial insulin responses in some treated individuals (Rendle et al, 2013).

Although metformin hydrochloride may be a useful adjunct in some individual patients, it should never replace the implementation of an appropriate diet and exercise management plan.

In PPID-affected horses with laminitis, serum insulin concentration at the time of diagnosis was positively correlated with the subjective severity of radiological changes consistent with laminitis (Tadros et al, 2019).

In a histological study on horses with PPID, those with lamellar pathology had high fasting serum insulin concentrations, whereas those without lamellar pathology had normal fasting insulin concentrations (Karikosi et al, 2016). Hyperinsulinaemia is estimated to have a prevalence of 32% of horses with PPID (McGowan et al, 2013). It is likely the development of concurrent hyperinsulinaemia in horses with PPID is multifactorial, and may be influenced by obesity, diet, activity and age. A direct pathophysiological association between PPID and hyperinsulinaemia has not been identified.

Pergolide mesylate, a dopamine receptor agonist, normalises pituitary hormone secretion through re-establishment of dopamine inhibition and improves long-term survival times for horses with PPID (Horn et al, 2019). It has been observed pergolide mesylate may improve insulin sensitivity in horses with insulin dysregulation (Durham et al, 2019). Hyperinsulinaemia should be managed by dietary and activity modification, similar to the management of hyperinsulinaemia in horses with EMS (Durham et al, 2019).

A long-standing perceived risk exists of iatrogenic laminitis following administration of glucocorticoids – so-called “steroid-associated laminitis”.

A case-control study demonstrated no significant difference exists between the incidence of laminitis in horses treated with oral prednisolone compared with time-matched controls (p=0.8; Jordan et al, 2017). Univariable analyses identified age, endocrinopathy and having a history of previous episode of laminitis as risk factors. Age and EMS were the major risk factors as determined by multivariable analysis. No association existed between mortality as a result of laminitis and prednisolone administration.

In a large prospective study of 889 horses to which glucocorticoids were administered therapeutically, the prevalence of laminitis over a 13-month period was low (0.6%; Potter et al, 2016). The development of laminitis was significantly associated with breed, the presence of underlying endocrinopathy and a history of previous laminitis (p<0.001). The type and route of administration of glucocorticoid was not associated with the development of laminitis.

Contrary to previous belief, administration of glucocorticoids does not appear to be a risk factor for the development of laminitis. However, this may also be a reflection of the doses administered and the presence of other concurrent risk factors, and is not necessarily a reflection of individual vets’ experiences.

In conclusion, several recent important developments have occurred that will have an impact on the diagnosis and prevention of laminitis in horses.

Recognition of the presence and radiological signs of subclinical laminitis – and of underlying endocrinopathies – is hugely important, and the prompt instigation of management changes may positively contribute to the prevention of acute laminitis and improvement of welfare.