19 Dec 2016

Laura Quiney and Sue Dyson consider the challenges of identifying the sources of pain causing lameness and poor performance in horses.

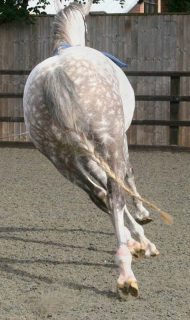

Figure 1. This horse had profound back pain and showed marked discomfort from lateral bending of the thoracolumbar spine when turned in small circles. Note the abnormal posture due to the thoracolumbar region being held stiffly in flexion, the outside hindlimb being placed to the outside of the circle, in an attempt to evade bending of the back, and the tail swishing.

Lameness and poor performance are common complaints for horses working in all disciplines, at all levels. Whether ridden professionally or recreationally, the presence of musculoskeletal pain or abnormality can have huge impact on horses being rideable and successful.

It can be challenging to definitively identify the source of lameness. This is especially true with subtle, multi-limb or referred lameness. Equally, lameness can only be seen under certain conditions. A comprehensive and detailed case history and physical examination are essential.

The ability to differentiate secondary pain from primary pain, particularly in the thoracolumbar region, is essential to prevent potentially erroneous diagnoses. The gait should ideally be evaluated under a variety of circumstances, including ridden exercise. Understanding the way horses may adapt their gait to avoid pain is important.

A judicious approach to diagnostic analgesia, combined with knowledge of its limitations, should allow identification of all sources of pain contributing to poor performance or lameness. An accurate prognosis and management plan will take the findings from each stage into account, including previous history, physical assessment of the horse, the effect lameness has on its performance and blocking pattern.

The search to identify one or more sources of pain in quadrupedal athletes and prey animals, which will try to hide signs of pain by nature, presents many challenges.

This is especially true for horses with subtle lameness or gait abnormalities that may only manifest under certain circumstances, neurological gait deficits, multi-limb lameness and those with multiple sources of pain in the same limb.

It is essential to have a thorough understanding of the biomechanics of the whole horse, discipline-specific training and competitive requirements, and to be critical of the diagnostic procedures and tests available. This allows informed decision making that leads to the most complete, accurate diagnosis possible and, subsequently, an accurate prognosis and tailored individual treatment and management plan.

The importance of a full, accurate case history is ubiquitous in all aspects of veterinary investigation. For lameness cases, it is important to know the work discipline and level the horse is worked and/or competed to, as well as understanding the terminology of the sport.

Understanding the demands of training and competition will not only aid successful identification of problems causing poor performance, but also in the development of a rational management or rehabilitation programme and to give a realistic prognosis.

As well as history directly pertaining to the perceived issue, the previous training and management of the horse can be directly relevant. For example, a horse that has become lame when starting to train or compete at a higher level may have had pre-existing problems it was able to cope with when working at a lower level with less athletic demands. Equally, a horse that has changed rider may be ridden differently, with alteration of stress on the musculoskeletal system, even if working at the same level as with the previous rider.

Changes in management – such as working on a different surface, starting to wear studs when jumping on grass and a new farrier – are all potentially relevant variables, because all may alter forces in the distal aspect of the limbs and predispose to injury.

Before the lameness examination, it is critical to ask the rider what the perceived problem is and under what circumstances they believe it manifests. Logically, if the complaint pertains to ridden exercise then lameness examination must include assessment when ridden.

The way to approach a physical examination is not to go specifically looking for the perceived problem – although it is the ultimate aim – but to systematically examine the horse and decide whether each structure is normal, insignificantly abnormal or significantly abnormal.

While the owner may pinpoint where he or she believes the problem to be, it is important to remember clinical signs often appear at distant sites to the source of lameness. For example, tension in the brachiocephalicus muscle and a shortened cranial phase to the step of a lame forelimb may appear to be pain in the shoulder region to laypeople, but reflect pain in the distal aspect of the limb (Dyson, 2011b).

Atrophy, tension and pain on palpation of the thoracolumbar epaxial muscles can commonly present as a result of stiffening of the thoracolumbosacral region secondary to hindlimb or forelimb lameness.

The horse should be assessed visually and by palpation in a familiar or stress-free environment, such as a stable. It is helpful to approach this in a methodical fashion to ensure nothing is missed. The horse’s posture, way of standing and response to palpation should be noted, as well as significant findings on palpation, including muscle tension, pain, atrophy and any areas of heat, swelling, or joint or bursa distension.

The limbs should all be assessed in both the weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing positions. The response to passive dynamic tests should also be assessed, including manipulation of the limb joints, thoracolumbar flexibility and stability in the dorsoventral and lateral planes, and degree of lumbosacral flexion.

It is generally best to visually evaluate muscle symmetry with the horse standing outside, on a level surface, standing squarely with the feet level and bearing weight equally. Although assessment of conformation is still largely based on empirical – rather than scientific – evidence, several common injuries seen in sports horses appear to be associated with conformation traits (Dyson and Murray, 2003; Dyson and Murray, 2012; Holroyd et al, 2013).

The hindquarters should be visually assessed for atrophy of the gluteal or quadricep muscle groups that may indicate chronic hindlimb lameness, atrophy or abnormal contours of all other muscles and levelness of the tubera sacrale, which can also be assessed by palpation.

The feet should be assessed from all angles to gain the most information on balance and symmetry, including when picked up. If a major problem exists with the shoeing or balance, or if the hoof horn quality is particularly poor, deferring further investigation until this has improved may be prudent.

History and physical evaluation can yield potentially important findings; however, always bear in mind areas of abnormality on examination are not always significant and, equally, lack of physical abnormality does not preclude injury and pain-causing lameness in the same region.

The inter-observer agreement for the subjective evaluation of lameness has been shown to be variable in several studies (Hewetson et al, 2006; Keegan et al, 2010; Hammarberg et al, 2016).

Keegan et al (2010) demonstrated the poorest agreement exists when the lameness is in a hindlimb, compared with a forelimb, and when the lameness is more subtle.

Several grading systems have been proposed; however, we know the degree of lameness varies depending on the circumstance – in hand versus lungeing on a soft surface, versus lungeing on a firm surface – and it may be best to grade and describe the lameness characteristics under each observed circumstance (Dyson, 2011a).

Objective assessment is now possible with the use of inertial measurement unit (IMU) gait analysis, which quantifies the head nod or hip hike (Pfau et al, 2015a; 2015b). However, not only do we not know enough about how sound horses move under different circumstances when evaluating IMU data, but this system does not take into account many other gait abnormalities seen as a result of lameness. While kinematic evaluation may be superior to subjective assessment in horses with unilateral lameness, we do not know if the technology is sophisticated enough to successfully identify horses with bilateral lameness or distinguish neurological gait abnormalities.

The horse should first be seen moving in hand on an even, hard surface. The horse should be evaluated at walk from the front, back and side. The slowness of stride makes this the easiest gait to assess how the feet are placed on the ground and the point of breakover. The horse should be watched turning in small circles in both directions (Figure 1). This can exacerbate pain in the front feet and the horse may appear reluctant to turn and transfer weight off the painful foot quickly. Reluctance to turn may also reflect cervical or thoracolumbar region pain.

Placement of the limbs should be assessed as this can identify proprioceptive deficits and help differentiate a neurological gait abnormality from lameness. A horse with hindlimb ataxia may circumduct the outside hindlimb excessively and place the foot to the outside. Backing the horse may also highlight neurological deficits or gait abnormalities, such as shivering.

Height of limb flight at walk and trot should be assessed. Decreased height may indicate lameness and a reluctance to flex the limb, and may be accompanied by a toe drag. Increased height of limb flight appears to be an expressive pace, but may indicate hypermetria in association with ataxia.

The distal excursion (extension or dropping) of the fetlocks should be assessed. Increased extension may indicate breakdown of the suspensory apparatus, while decreased extension may indicate reluctance to fully bear weight through the limb. At trot, the horse should be assessed from behind, in front and the side while moving at a consistent, steady speed. Attention should be paid to pelvic displacement (hip hike), head nodding, length of step (a short-stepping horse may have bilateral lameness), expressiveness, straightness (a horse with hindlimb lameness may trot crookedly; Figure 2), rhythm and swing of the thoracolumbar region.

If asymmetry of the hindquarter muscles or pelvis is noted during the physical examination, this should be borne in mind when assessing pelvic symmetry at the trot. A horse with asymmetrical hindquarter musculature may give an untrue impression of asymmetrical pelvic displacement if assessing movement of the hindquarters. Assessing the relative movement of the tubera coxae and tubera sacrale is more accurate.

Some lameness appears more pronounced, or is only really seen, when decelerating from trot to walk, so the whole length of the trot up should be carefully watched. It is, therefore, also important to see the horse trotting in a straight line for long enough to assess acceleration, steady speed and deceleration independently. Equally, horses with neurological deficits may display more marked clinical signs during deceleration, such as loss of rhythm, erratic foot placement and increased movement of the hindquarters.

It is useful to assess the horse being lunged on soft ground, such as an arena. Some lameness is exacerbated by working the horse on a circle, although many will adapt their gait to avoid pain and, thereby, reduce lameness. Adaptations in gait or posture to reduce pain can be identified and should raise suspicion in the absence of overt lameness. Lame horses may lean inwards with their bodies, look out of the circle, hold the thoracolumbar region stiffly, have a shortened cranial phase of the step or have irregular rhythm (Figure 3). Horses with hindlimb lameness may swing the inside hindlimb under the trunk during protraction, presumably to limit flexion of the limb if this elicits pain. Leaving the limb behind (increased caudal phase) during downward transitions, or not pushing evenly into upward transitions, may also indicate hindlimb lameness.

In addition to trotting, the quality of transitions and canter can be revealing. A sound horse should be forward-going and maintain good rhythm, balance, movement of the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral regions and, in canter, produce a regular and fluent three-time gait without becoming disunited or showing conflict behaviour.

Assessing the horse when lunged on a firm surface with good grip may exacerbate lameness, especially that attributed to foot pain.

Unless the horse is unbroken, unsafe to ride or has marked lameness in hand that does not warrant ridden evaluation, it is crucial to see the horse ridden – especially because the owner complaint usually pertains to a problem identified when ridden.

Many lameness and poor performance problems are exacerbated or, more importantly, only manifest when ridden (Licka et al, 2004; Dyson and Murray, 2003; Figure 4). This may be for several reasons, including the interaction of the tack and rider, the horse being asked to work in an outline, preventing the horse from adopting postures or gait abnormalities that reduce the source of pain and visible lameness, and the increased athletic demands of ridden work.

Assessing the rider-tack-horse relationship is important. The skill of a rider can significantly change the way of going of a horse. A skilled rider may be able to improve the way of going in the face of lameness by riding strongly, but, equally, a horse may appear more lame with a skilled rider because he or she is likely to demand more of it. An unskilled rider who is unbalanced may create gait abnormalities, or a horse may appear sounder when ridden by an unskilled rider because less is being asked of it. Seeing the horse ridden by the usual rider is, therefore, important.

It is important to assess the fit of the saddle to identify any pressure points that may cause back discomfort or asymmetry of flocking that may cause saddle slip. Research has correlated the presence of saddle slip to hindlimb lameness, with abolition of lameness by diagnostic analgesia resolving saddle slip (Greve and Dyson, 2013).

The horse should be assessed at walk, trot and canter, including lateral work, and over a fence if problems have been noted when jumping. As well as looking for signs consistent with lameness, a horse in pain may show general signs, such as not being forward-going, displaying conflict behaviour or being spooky.

Sacroiliac joint region pain is often exacerbated when ridden and the quality of canter, including flying-changes, depending on the level of training, should be assessed (Barstow and Dyson, 2015). In canter, thoracolumbar stiffness, poor separation of the hindlimbs spatially and temporally, poor bit contact, kicking out, bucking, bunny-hopping and tail swishing are all rather non-specific signs of pain, but may reflect sacroiliac joint region pain (Barstow and Dyson, 2015).

Another reason to evaluate the horse ridden is to assess whether the lameness deteriorates or improves with exercise. It is important to identify inconsistent lamenesses, before proceeding with diagnostic analgesia, to avoid erroneous interpretation of the response. When performing diagnostic analgesia, it is important to reassess the horse under the appropriate conditions – those under which clinical signs were initially seen.

Few causes of lameness have gait abnormalities truly pathognomonic and in the absence of localising signs – such as heat, swelling or pain – the sites of pain must be determined by diagnostic analgesia (nerve or joint blocks).

Key to correctly interpreting diagnostic analgesia is a thorough understanding of the limitations of each block, potential for confounding results and a critical, unbiased evaluation of gait alteration. The majority of nerve blocks are easily performed; however, accurate needle placement and choice of volume of local anaesthetic solution used are very important. For example, using too large a volume of local anaesthetic in a synovial space may increase diffusion into adjacent tissues and lead to false-positive results (Schumacher et al, 2001). Using too small a volume in a synovial space may lead to false-negative results.

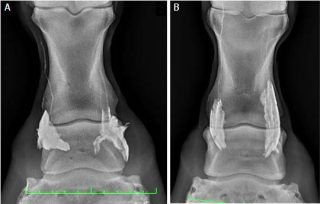

Proximal diffusion of local anaesthetic following perineural analgesia should also be considered when interpreting nerve blocks, and the greatest diffusion of contrast medium has been shown to occur in the first 10 minutes following injection (Nagy et al, 2009). Nagy and Malton (2015) demonstrated the importance of both needle placement location and volume of contrast medium in minimising proximal diffusion after palmar digital nerve blocks, concluding less than, or equal to, 2.5ml of local anaesthetic deposited at the level of the ungular cartilages, and not proximal to them, would maximise specificity of this nerve block (Figure 5).

Inadvertent penetration of a synovial structure can occur with perineural injection, depending on technique and proximity of the target nerve (Nagy et al, 2012). Equally, diffusion can occur from a perineural deposition site into a synovial space and vice versa, so it is important to bear this in mind from both a sterility and diagnostic point of view.

Contino et al (2015) demonstrated diffusion using both contrast medium and mepivacaine studies in vivo following analgesia of the tarsometatarsal joint and the deep branch of the lateral plantar nerve. The results support the practice of cross-blocking by performing both perineural and intra-articular analgesia on separate occasions if one results in improvement in lameness, to reduce the chance of misleading results and subsequent misdiagnosis due to diffusion.

The proximity of extra-articular structures should always be borne in mind when performing intra-articular diagnostic analgesia. For example, pain in association with a collateral ligament of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) or a suspensory ligament branch injury may improve following intra-articular analgesia of the DIP, or metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints, respectively (Dyson et al, 2004; Minshall and Wright, 2006).

In cases with multilimb lameness, teasing out the relative importance of each, in relation to poor performance, can be difficult. We know referred, or so-called compensatory, lameness can be seen – for example, a horse with hindlimb lameness may have a head nod mimicking an ipsilateral forelimb lameness in the absence of forelimb pain.

Evaluating the horse under different circumstances, as aforementioned, should allow the observer to determine the lame, or lamest, limb and identify the presence of referred versus multilimb lameness. Of course, the two may also co-exist.

When starting diagnostic analgesia in a horse with multilimb lameness, it is important to always start, and continue thereafter, with blocking the lamest limb. In some cases, multilimb lameness is not identified at the initial evaluation. However, a horse with apparent unilateral lameness may show lameness in other limbs once the lamest limb has been successfully blocked.

When dealing with lameness in more than one limb, it is important to recognise the local anaesthetic solution has a limited duration of effect. If blocks of the lamest limb start to wear off, this may preclude further investigation of any remaining sources of pain causing lameness. It is, therefore, important to assess the horse promptly and efficiently between blocks and allow sufficient time for investigating all lame limbs.

When evaluating horses following blocking, it is important to remember complete resolution of lameness is sometimes seen, but, equally, residual lameness or gait abnormalities may persist in the absence of an additional source of pain. Experience is a huge factor in the ability to distinguish between horses that have improved following a block, but have another source of pain causing lameness, and those that have improved significantly enough to preclude the presence of another source of pain in the limb. For example, it is not unusual for horses with pain associated with the stifle to show improvement, rather than elimination, of lameness (Dyson, 2002).

An improvement in response to intra-articular analgesia of the stifle may not be seen until up to 90 minutes after injection, so it is important to wait long enough before declaring the block as being negative. A delayed response of up to 60 minutes can be seen following perineural analgesia of the tibial and fibular (peroneal) nerves. A successful block at this level may affect motor function and increase toe drag. It is important, therefore, to assess all other features of lameness, including pelvic displacement, step length, rhythm and push, and not mistake a newly observed toe drag for worsening of lameness or a persistent toe drag for lack of response.

By performing a thorough assessment, including gait evaluation under different circumstances and ridden exercise wherever possible, and performing comprehensive diagnostic analgesia, it should be possible to locate all regions of pain causing lameness and poor performance. This provides clinicians with a list of problem areas warranting further investigation using diagnostic imaging.

It is crucial to interpret the results of diagnostic imaging in light of the clinical picture and blocking pattern to assign the relative importance of findings. When it comes to determining the prognosis for an individual horse, the findings of initial examination should be revisited. This includes the degree to which the horse’s work is affected by the problems, the presence of any risk factors or poor prognostic indicators, such as poor conformation, and the potential to improve any aspect of management that may help the horse cope with the problems.

The response to intra-articular analgesia may help predict the potential benefit for intra-articular medication.

The treatment and management plan should consider all of these factors and be mindful of the rider’s expectations of the horse. Any treatment plan should aim to improve the causes of lameness or poor performance, while maintaining physical strength and stability, to allow the horse to eventually return to its level of work without being at increased risk of subsequent injury due to physical deterioration in the rehabilitation period.

Any other weaknesses identified on initial physical examination, even if not directly related to pain causing lameness – for example, poor development of the thoracolumbar epaxial muscles – should be addressed and steps taken to improve and maintain strength or stability to optimise overall health.