5 Jun 2017

Romain Paillot, Adam Rash and Camilla Strang discuss surveillance efforts and the importance of following recommended vaccination schedules.

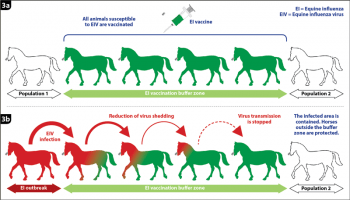

Figure 3. Emergency equine influenza vaccination. (3a) Principle of the vaccination buffer zone between two horse populations. (3b) Containment of the infected area through an effective reduction of virus shedding and disease transmission, with subsequent protection of the horse population outside the buffer zone.

Equine influenza (EI), one of the most important and contagious respiratory diseases of horses, is characterised by an elevation of body temperature and frequent coughing.

The causative agent is an influenza A virus – EI virus (EIV) subtype H3N8 – which targets epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract. Following infection, morbidity is high and the risk of secondary bacterial infection is important.

Beyond the welfare issue, the financial consequences may be significant in cases of large EI outbreaks. To date, surveillance and vaccination prove to be one of the best combinations to prevent and control EI in our horse population.

Disease surveillance provides essential information about how and where outbreaks occur. It also improves our understanding of the pathogen and how it constantly evolves to evade natural and/or vaccine immunity.

In the case of EIV, this information is essential to produce effective vaccines. As a World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) reference laboratory for EI, the AHT investigates how EIVs evolve through studying outbreaks and viral isolates around the world.

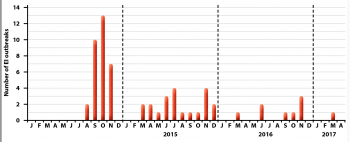

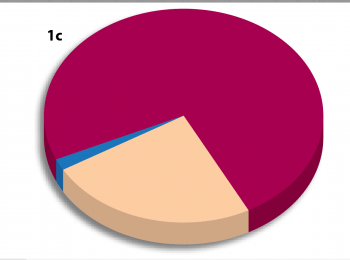

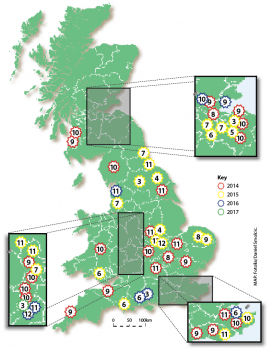

Despite the availability of several vaccines, EI remains a threat to the UK horse population. In the past three years, several EI outbreaks have been confirmed by the AHT EI surveillance programme, which is supported by the Horserace Betting Levy Board (Figure 1).

While all information is not always available, it is important to note the majority of EI cases concern unvaccinated horses or animals with a lapsed vaccination history. These data clearly illustrate the importance of EI vaccination, but also highlight EIV is still circulating in the UK.

EI outbreak details and updates are posted on the AHT’s EquiFluNet website – www.equiflunet.org.uk – and alerts are sent through the @equiflunet Twitter account and the Tell-Tail text messaging service, provided by Merial Animal Health; to register, visit www.ewagroup.com/merial/alertservice

EI vaccination has a proven record of efficacy in endemic zones and when used in an emergency in the face of an imminent risk of infection and outbreak.

Vaccines are expected to reduce clinical signs of disease, and improve overall welfare and recovery. A significant reduction of virus shedding is also necessary to limit the risk of transmission of the virus to other susceptible animals and subsequent propagation of the disease.

Several EI vaccines are available in the UK, and all demonstrate field and experimental efficacy. Protection against EI induced by vaccination is mostly dependent on the production of circulating antibodies, which will recognise and neutralise the EIV before it can infect the horse. Most EI vaccines will also stimulate cell-mediated immunity, which acts as a second line of defence against the virus by clearing virus-infected cells.

The following elements should be considered to optimise the effectiveness of EI vaccination and subsequent protection:

In some cases, administration of an EI vaccine may induce some mild reactions – such as transient fever and/or local inflammation – which indicate the horse immune system is responding to immunisation. These reactions are not unexpected, but should remain limited in terms of duration and severity.

When observed, adverse effects of vaccination – including failure to protect against an EIV infection – should be reported to the VMD and vaccine manufacturer.

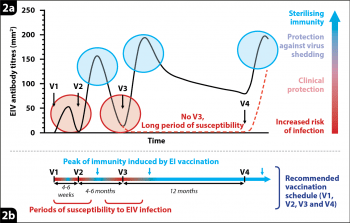

As illustrated in Figure 2, protection induced by EI vaccination will fluctuate through time. It is, therefore, important to follow the appropriate schedule of vaccination, provided by the vaccine’s manufacturer, to maximise levels of protection provided by EI vaccines.

Partial protection against infection, a reduction of clinical signs of disease, and virus shedding have been observed as soon as a few days after the first immunisation. However, this initial protection is short-lived. A more robust protection against EI usually appears about two weeks following the second vaccination. This was illustrated by a case of EI reported to the surveillance programme. A five-year-old horse had received its first immunisation, but was exposed to EIV two months later while waiting to receive its second vaccination. The juvenile and immature immune response, induced by the first immunisation, was not sufficient to provide significant protection and was overwhelmed by EIV, resulting in the horse developing clinical signs of disease. This highlights the need to follow the vaccination schedule specific to the EI vaccine used, whenever possible, to minimise the periods of susceptibility.

Protection could also significantly decrease between immunisations, especially following the second dose of the primary course of vaccination when an immunity gap frequently occurs between the second and third vaccinations. The third immunisation of the primary course is extremely important for inducing long-lived immunity.

Vaccination of the pregnant mare is useful, as maternal protective antibodies will be passed to the foal through colostrum ingestion – providing protection to the young foal for several months after birth. However, the presence of maternal-derived antibodies may interfere with some EI vaccines. On this basis, it is advised to respect the minimum age of EI vaccine administration provided by the manufacturer.

EI vaccine protection may be reduced in old horses due to a reduction in the immune response in older animals.

Emergency vaccination could help significantly reduce the size and frequency of EI outbreaks, as illustrated in Australia when 75,000 horses were infected with EIV in a five-month period. An emergency EI vaccination programme was implemented four weeks after the start of the epizooty, and involved between 130,000 and 170,000 horses. One striking action was to create vaccination buffer zones, or “rings”, of 10km or wider around identified infected areas. Horses within these zones were vaccinated with the canarypox-based EI vaccine.

As illustrated in Figure 3, vaccination buffer zones aim to contain and stop the disease spread to protect horse populations outside these areas. When infected with EIV, a naive, unvaccinated horse may be infectious and spread the disease for several days, usually up to one week.

All commercialised EI vaccines significantly reduce the duration of virus shedding and, therefore, the duration of transmission and disease spread. This characteristic is fundamental for the successful implementation of buffer zones and outbreak controls.

In Australia, a combination of emergency vaccination, surveillance and horse movement controls allowed the Australian veterinary authorities to eradicate EI. Australia regained its EI-free status one year after the last EI case.

The same principle applies to countries where EI is endemic. A high EI vaccination coverage will act in the same way as a vaccination buffer zone, by reducing the duration of virus shedding if animals are infected, and limiting the propagation of the pathogen and disease.

For influenza, it is usually accepted a good level of protection could be achieved if 70% to 80% of the targeted population is vaccinated.

Regretfully, the EI vaccination coverage of the horse population in the UK is likely to be well below this threshold, which could, in part, explain why EI is still circulating.

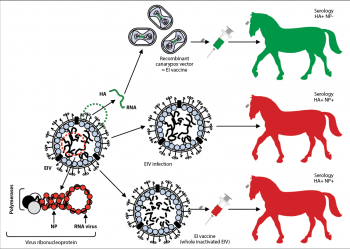

The ability to differentiate infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) is important to:

Regretfully, only one EI vaccine commercially available in the UK has DIVA ability.

The DIVA concept is explained and summarised in Figure 4.

Due to active surveillance and the availability of efficacious vaccines, EI cases remain sparse in the UK, isolated and limited to unvaccinated horses or animals with a lapsed vaccination history. However, the threat should not be underestimated; EIV is still circulating in the UK horse population, waiting for our vigilance to falter.

Clinical Assist