27 Mar 2018

The author updates readers on currently circulating viruses, clinical signs to look for, diagnosis, treatment, surveillance and vaccination.

Figure 1. Sampling time points of nasopharyngeal swabbing and paired serum samples for equine influenza diagnosis. Reprinted with permission from Equiflunet.org.uk

Equine influenza (EI) remains a major cause of respiratory disease in horses around the world, with only a few countries, including New Zealand, Australia and Iceland, free from the virus.

The disease remains endemic in the UK as, although the majority of competition horses are vaccinated, the proportion of vaccinated pleasure horses is much lower and, as such, they act as a reservoir of virus. EI is caused by the single-stranded RNA (ribonucleic acid) orthomyxovirus influenza A.

Common to all influenza A viruses are the surface glycoproteins haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), which are central to virus entry and exit into cells. HA is an important component of commercial vaccines, as it is a major target for neutralising antibodies.

The importance of NA to EI immunity is unknown, but antibodies to human influenza virus NA have been shown to contribute to protection (Halbherr et al, 2015).

All currently circulating EI viruses belong to the H3N8 subtype. The previous H7N7 subtype is now thought to be extinct, having not been isolated for 30 years. The H3N8 virus originated in birds and, since jumping species to the horse, has diverged into different lineages and sub-lineages.

In the early 2000s, the Florida sub-lineage further divided into clade 1 and clade 2 subtypes, which remain the dominant circulating viruses. Clade 1 EI viruses have predominantly been isolated in North America, while the majority of Florida clade 2 viruses have been isolated in Europe and Asia (Rash et al, 2017).

The clinical outcome from viral exposure largely depends on immune status varying from a mild, inapparent infection to severe disease. Young male racehorses appear to be more susceptible to EI infection than their female cohort (Barquero et al, 2007), although the biological reasons for this are unclear.

Unvaccinated horses develop pyrexia, lethargy, anorexia and a harsh, dry, unproductive cough within one to five days of exposure. Conjunctivitis, submandibular lymphadenopathy and a mild serous or mucoid nasal discharge may also develop.

Clinical disease often lasts only a few days, and mildly affected horses recover uneventfully within two to three weeks. Vasculitis, myositis and myocarditis are seen infrequently.

Influenza viruses replicate within respiratory epithelial cells, resulting in destruction of tracheal and bronchial epithelium and cilia. It takes approximately 21 days for the epithelium to regenerate, during which time it is susceptible to opportunistic bacterial infection. Such secondary infections are usually accompanied by purulent nasal discharge, prolonged pyrexia, lethargy and malaise, and they can even lead to pneumonia and death in vulnerable horses.

This period of increased susceptibility to opportunistic infection can last up to 100 days post-infection, and care should be taken not to overwork or stress the horse during this timeframe. Complications are minimised by restricting exercise and improving airway hygiene.

Horses with only partial immunity to EI, due to irregular vaccination, suboptimal vaccination response, or the use of outdated vaccine strains, typically show signs of milder, non-specific respiratory disease. Such horses also shed lower viral loads for shorter periods of time (Paillot et al, 2013), but can still be important in disease transmission during outbreaks.

Definitive diagnosis is often not sought, but is extremely useful for surveillance purposes, and is offered free of charge by the Animal Health Trust (AHT) through its Equiflunet scheme. Diagnosis can be made by nasopharyngeal swabs or paired serum samples.

Patient-side ELISA assays have been used as a screening tool for horses entering quarantine and appear useful (Galvin et al, 2014).

Diagnostic samples should be taken from any unvaccinated horse with typical influenza signs, vaccinated horses with non-specific respiratory signs and unvaccinated in-contact horses. Nasopharyngeal swabs should be taken no longer than two to three days after clinical signs first appear to maximise the chances of obtaining sufficient virus (Figure 1).

After this timeframe, it may be more useful to take swabs from in-contact animals, as virus shedding occurs prior to clinical signs of disease, or to use paired serum samples taken on or after 14 days apart to detect an antibody response (haemagglutinin inhibition assay).

These serum samples can be taken further into the disease process (Figure 1), even after virus excretion is too low to detect with a swab, although diagnosis is delayed.

If EI is suspected, the individual should be isolated with appropriate barrier nursing. Close to a 100% infection rate within two to three days can be expected in a group of unvaccinated individuals, whereas the spread of EI in vaccinated horses is less explosive due to slower disease transmission.

Symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs and improved airway hygiene is often warranted. Horses should receive a minimum of three weeks’ rest to allow recovery of the respiratory tract epithelium. Exercise has been shown to decrease T-cell mediated immunity and to increase susceptibility of vaccinated horses to EI infection when compared to non-exercised vaccinates (Folsom et al, 2001). Therefore, resting in-contact horses may be a sensible precaution.

Aerosolised virus spreads rapidly across long distances by droplets, so 100m isolation from susceptible horses is recommended. The virus can survive for limited periods outside of the host, so fomite transmission is also possible. However, the virus is fairly labile, so simple hygiene measures – such as hand washing, minimising horse-to-horse contact and controlling fomites – significantly reduce the risk of disease transmission.

Prevention of EI is best achieved via a combination of biosecurity and vaccination. Strict isolation of new arrivals for two weeks reduces the risk of disease introduction – a breakdown of quarantine biosecurity has been cited as central to the initiation of the 2007 Australian EI outbreak when, ultimately, more than 75,000 horses were infected (Callinan, 2008).

Monitoring the rectal temperature of in-contact horses twice daily is sensitive for detection of new clinical cases. In the event of an outbreak, vaccination of primed horses to induce a rapid, anamnestic response may be useful and is recommended for in-contact horses with no clinical signs in the preceding 24 hours (Slater et al, 2014).

Booster vaccination appears to be effective even when the vaccine does not contain the circulating virus strain, or does not match the previously administered vaccines (Barquero et al, 2007).

Protection against EI largely relies on the production of antibodies to the HA glycoprotein, which can be produced following exposure to the virus or following vaccination.

A definite correlation between HA antibody titres and protective immunity against EI has been verified in both experimental challenge studies and the field (Mumford et al, 1994; Newton et al, 2000). It is estimated approximately 70% of a given horse population needs to be fully vaccinated to prevent EI epidemics (Baker, 1986). The true vaccination rate of the UK horse population is difficult to determine. A questionnaire study of UK horse owners cited 80% vaccination uptake (Bambra et al, 2017), but voluntary response bias is likely to have influenced this figure.

Owners can become complacent to the threat of EI due to the infrequent nature of large-scale outbreaks in the UK. The UK typically reports 10 or 11 outbreaks of EI per year, with most confirmed cases occurring in unvaccinated horses or horses with lapsed vaccination. This is likely to be a gross under-representation of the true situation, however, due to owners or veterinary surgeons failing to investigate mild infections.

Larger outbreaks occur when a mismatch exists between circulating virus and vaccine strains.

A period of increased susceptibility, known as an immunity gap – when antibodies have significantly waned – is known to occur between second and third vaccinations (Cullinane et al, 2001; Gildea et al, 2011a). Indeed, vaccinated horses experimentally infected with EI two to three months after the second immunisation have been able to infect naive sentinels (Paillot et al, 2013).

This immunity gap occurs regardless of whether manufacturer or Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) recommended vaccination intervals are followed. However, increasing the interval between vaccinations increases the vulnerable period between first and second, and second and third, doses (Cullinane et al, 2014), indicating manufacturer guidelines should be followed if possible.

Suboptimal vaccination response in a small proportion of horses is a recognised phenomenon, and such horses have been identified as highly susceptible to EI during outbreaks (Gildea et al, 2013). Additionally, the risk and size of an EI epidemic increases significantly if poor vaccine responders are concentrated in a small area close to the index case (Baguelin et al, 2010).

Such poor responders can be divided into horses that fail to mount a substantial response to the first vaccination (only) and those that repeatedly do not produce or sustain adequate immunity. Maternally derived antibodies interfere with vaccine response and, therefore, it is recommended initial doses of inactivated or subunit vaccines should not be given until after six months of age, regardless of some manufacturer datasheet recommendations.

The use of the canarypox virus-based vaccine (Proteqflu: Merial) may circumvent the neutralising effect of maternal antibodies on vaccine efficacy (Paillot et al, 2006).

Weanlings and yearlings have a reduced response to first EI vaccination compared with two and three-year-old horses (Cullinane et al, 2014), and epidemiological analysis of EI outbreaks has shown earlier vaccination appeared to increase the risk of horses suffering influenza infection later in life (Barquero et al, 2007).

Similarly, older (more than 20 years old) horses show “immunosenescence” and a reduced antibody response to standard vaccination compared to younger horses (Adams et al, 2011). Poor initial vaccination response is also influenced by vaccine type, and has been reported to be as high as 79%, depending on the age of the horse and the vaccine used (Gildea et al, 2011a; 2013).

The whole inactivated EI vaccine with carbopol adjuvant (Duvaxyn IE: Elanco) induced a greater HA antibody response and had a lower rate of poor responders in all age groups than other vaccines (Gildea et al, 2011a; 2013).

Analysis of post-race samples showed up to 7.5% of Thoroughbred horses had no detectable levels of HA antibody, despite vaccination records compliant with FEI regulations (Daly et al, 2004). A study of antibody response to booster vaccination in 44 National Hunt horses showed 41% did not demonstrate a significant rise in HA antibodies following booster vaccination, and two had no detectable increase in antibody titre (Gildea et al, 2011b).

Pre-existing HA antibody titres significantly correlated with this lack of response to booster vaccination (Gildea et al, 2011b), illustrating the fine line between immunity gap and immune interference at the time of the booster immunisation.

Epidemiological analysis of a 2003 Newmarket EI outbreak determined vaccination more than thee months previously provided a 10 to 15-fold increased risk for infection, regardless of vaccine brand (Barquero et al, 2007). This study also determined that use of an aluminium hydroxide adjuvanted vaccine containing Prague/56, Newmarket/1/93 and Newmarket/2/93 antigens (Prequenza: MSD Animal Health) – administered both as the last vaccine type and the first vaccine type containing an American lineage virus – was associated with an increased risk of infection compared to other vaccine types (Barquero et al, 2007).

Suboptimally responding horses are usually partially protected and can present with a subclinical form of EI that is likely to go unnoticed. Importantly, these horses may shed a large amount of infectious virus for longer periods and be significant in initiation of epidemics. Indeed, poor vaccine responders in the quarantined population were retrospectively identified as the source of EI that spread to the wider horse population in the Australian epidemic (Callinan, 2008). A personalised approach to vaccination utilising measurement of HA antibody titres has been suggested for improving immunity in such animals and conferring better herd protection (Gildea et al, 2011b).

Mathematical modelling techniques have been used to investigate the effects of poor vaccine responders during a large outbreak affecting multiple yards, and also the use of vaccination in the face of an outbreak (Baguelin et al, 2010). Interestingly, the majority of equine influenza outbreaks appear to be limited and fail to spread.

Vaccination in the face of an outbreak appears to convey a significant benefit for an individual trainer, and this effect is augmented if horses on other yards are also revaccinated.

Older vaccines use whole inactivated virus combined with a chemical adjuvant. More recent inactivated subunit vaccines contain HA and NA proteins.

Inactivated vaccines stimulate strong humoral immunity, mainly directed against HA, but immunity tends to be short lived and vaccine strains need to be relevant to circulating virus strains to provide field protection. Induction of cell-mediated immunity, which is thought to be important in the development of long-lasting immunity from natural infection, has not been reported in horses in response to these vaccines.

A modified live canarypox virus-vectored EI vaccine has been available since 2003. HA proteins expressed by cells infected with the recombinant canarypox vaccine vector result in the induction of both antibodies and priming of cell-mediated immune responses (Paillot et al, 2006), and this vaccine has been shown to protect against a non-vaccine EI strain (Toulemonde et al, 2005).

A study of 102 Thoroughbreds in training in Ireland indicated 95% were vaccinated with more than one vaccine brand (Ryan et al, 2015). The manufacturers of Duvaxyn IE and Equip F advise these vaccines should not be used interchangeably with other products, and that a new primary course should be started if a brand change occurs.

However, horses vaccinated with different vaccine products demonstrated significantly higher antibody responses than those vaccinated with a single product, and the use of three different types of vaccine in the vaccination history appeared to reduce prevalence and risk of EI infection during a Newmarket outbreak (Barquero et al, 2007).

Vaccinated ponies challenged with non-vaccinate strains at the peak of immunity, two weeks after the second immunisation, showed significant protection from infection and reduced viral shedding (Daly et al, 2007; Paillot et al, 2010 and 2013). However, the quality of mid and long-term cross protection is often unknown and likely to be inferior to protection induced by an equivalent EI vaccine matching the circulating isolates (Paillot, 2014).

Significant differences between circulating virus and vaccine virus strains generates a situation where vaccines provide reasonable clinical protection, so disease is mild and short lived, but infected animals shed large amounts of virus and fuel spread of infection.

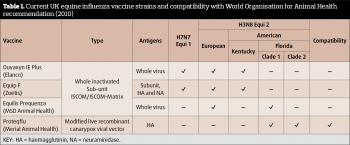

Current recommendations (last updated 2010) from the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) recommend both clade 1 and 2 subtypes are included in EI vaccines. Of the four vaccines available in the UK, only one (Proteqflu: Merial) meets these guidelines (Table 1). Logically, it would therefore seem prudent to use this vaccine for optimal protection; however, other vaccines do appear to offer some degree of cross protection to clade 2 strains (Paillot et al, 2013; Pouwels et al, 2014). The reasons for this response are unclear, but likely involve cell-mediated, as well as humoral, immunity (Paillot et al, 2013).

Mathematical modelling has been performed to evaluate the impact of circulating EI virus strain drift from vaccine strain (Park et al, 2004). The model was based on a Thoroughbred race training yard and indicated that mismatches between vaccine and outbreak strains do make a difference to the likelihood that a population will be protected.

Like other influenza viruses, EI undergoes antigenic drift through minor alterations of the surface glycoprotein amino acid structure. Modification of the HA molecule particularly aids evasion of immunity acquired from previous infection or vaccination.

The AHT runs the surveillance scheme Equiflunet to monitor genetic and antigenic changes in EI viruses circulating in the UK. The scheme is sponsored by the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) and provides free advice and free diagnostic testing for EI to all practices registered with the scheme. It also provides communication alerts during UK outbreaks.

The information collected from nasal swabs and paired blood samples allows comparison of circulating viruses with virus strains in commercial vaccines, and thus generates industry recommendations regarding vaccine updates.

Practices can register for the scheme at www.equiflunet.org.uk