24 Jul 2017

Common physiological and pathological murmurs and dysrhythmias found in the horse, when to undertake further diagnostic procedures and what the likely consequences may be regarding pathological disease for future performance and safety for ridden work are covered in this article.

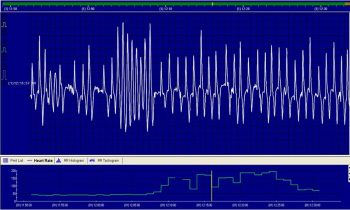

Figure 1. This is a resting (top) and exercising (bottom) ECG from an 18-year-old Warmblood gelding. This horse had a murmur consistent with mitral regurgitation and, on echocardiography, had an enlarged left atrium and ventricle. The horse had one ventricular premature depolarisation at rest, but had evidence of ventricular tachycardia at peak exercise. Note how regular this rhythm looks (and would sound). This horse was retired from ridden work and found dead in the field three years after this evaluation.

Cardiac murmurs and dysrhythmias are a common finding in the adult horse and the majority are physiological. However, it is necessary to be able to differentiate between variations of normal and abnormal to ensure potential performance and safety-limiting conditions are identified and appropriately evaluated.

Unlike small animals, horses rarely present in heart failure, but that does not mean they do not have cardiac modelling changes and rhythm disturbances at exercise.

Unlike in small animals, diastolic murmurs are a common and concerning finding in the adult horse as they are often due to aortic regurgitation, and being able to differentiate them from systolic murmurs can be extremely helpful for decision-making.

Palpation of the peripheral pulse or observation of jugular filling can help differentiation between systolic and diastolic murmurs. If the jugular vein fills at, or just after, the start of the murmur then it is systolic; similarly, if the pulse can be palpated at, or just after, the start of the murmur then it is systolic.

The shape and character of murmurs is determined by valve (or hole) geometry. Those murmurs associated with the aortic valve are usually decrescendo in shape and have a blowing or musical quality, whereas those associated with the mitral and tricuspid valves are plateau shaped and harsh in character.

Heart sounds can be extremely valuable to aid differentiation between the two most common dysrhythmias: second-degree atrioventricular block and atrial fibrillation. Horses usually have three or four audible heart sounds. Between 80% and 90% of horses have a fourth heart sound (S4), which is the sound closely associated with the first heart sound (S1) and corresponds to active atrial contraction. It is, therefore, never found in horses with atrial fibrillation.

Additionally, horses often have variable jugular filling corresponding to variations in R-R interval, which will not be found in horses with second-degree atrioventricular block.

Pulse quality can provide some information about heart size. The difference between systolic and diastolic pressure is an estimate of stroke volume and, therefore, left ventricular size. As such, horses with heart murmurs – usually those associated with aortic regurgitation, and occasionally mitral regurgitation or ventricular septal defects (VSDs) – that have bounding or “waterhammer” pulses should not be ridden until further evaluation is undertaken, as this finding is suggestive of increased left ventricular size.

It was once proposed differentiation between physiological and pathological murmurs and dysrhythmias could be achieved by auscultation after exercise. However, latest studies have shownthis is not the case. Murmurs are caused by turbulent blood flow. When animals exercise, blood flow may become more turbulent, thus increasing murmur grade, or become more laminar, thus decreasing grade.

It is also more challenging to accurately auscultate hearts at higher heart rates – atrial fibrillation sounds much more regular at higher heart rates (Figure 1). Therefore, murmur and dysrhythmia decision-making regarding likely diagnosis and further evaluation should relate to findings at rest.

The top differential diagnoses for left-sided systolic murmurs are physiological aortic flow murmurs, mitral regurgitation, left-sided murmur associated with VSDs (pulmonary flow murmur or functional pulmonic stenosis) and, in the sick horse, a “haemic” murmur secondary to hypovolaemia.

Physiological aortic flow murmurs are found in a large number of horses and are caused by turbulent flow of blood in the aortic sinus. They are grade three or less, holosystolic or shorter, with a focal point of maximal intensity high up in the left fourth intercostal space and decrescendo in nature.

Mitral regurgitation is usually due to valvular degeneration and modelling, although it can also be associated with mitral valve prolapse or endocarditis. It can be any grade, the murmur can be holosystolic (between the heart sounds) to pansystolic (obscuring one or more heart sounds), it is harsh and is plateau-shaped, with a point of maximal intensity in the fifth (or fourth) intercostal space.

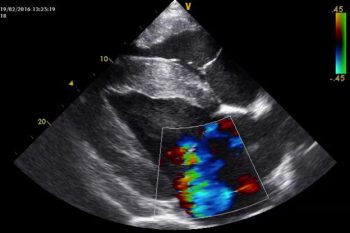

It is recommended murmurs of grade three or greater should undergo further evaluation, which will usually constitute echocardiography (Figure 2). Electrocardiography at rest or exercise may be warranted if rhythm abnormalities are present at rest or chamber enlargement is identified with ultrasound.

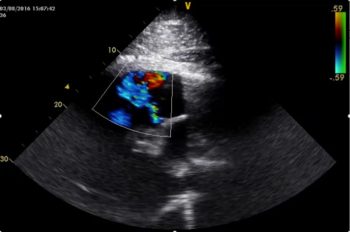

The top differential diagnoses for diastolic murmurs are aortic regurgitation or diastolic squeaks. Pulmonary regurgitation is an extremely rare finding (Figure 3).

Diastolic squeaks are very distinctive – like someone sitting on a pin. The exact cause is unknown, but these squeaks are usually found in young or flighty animals with high stroke volumes or higher heart rates. They will usually disappear as heart rate falls, but can be present more of the time in some individuals. They are not graded, but are early diastolic murmurs and are squeaky in nature.

Aortic regurgitation is usually caused by degeneration and nodule formation on the cusp of the aortic valve. It is usually first found in middle-aged to older horses. Murmurs can be any grade, holosystolic or pandiastolic, decrescendo and are blowing or musical in nature, with a point of maximal intensity in the left or right fourth intercostal space.

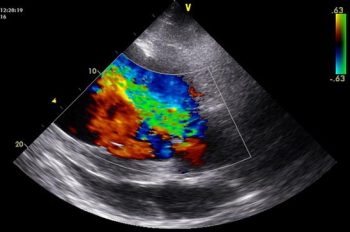

These murmurs should be evaluated if they are greater than grade three and horses will require an exercising electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography (Figure 4). Exercising ECGs should be undertaken at a similar level of activity usually undertaken.

The top differential diagnoses for right-sided systolic murmurs are tricuspid regurgitation and VSDs. Signalment will often be helpful in prioritising the most likely diagnosis. VSDs will most commonly be identified in Welsh section A ponies and Arabians, whereas tricuspid regurgitation will be found in Thoroughbreds.

Tricuspid regurgitation can be described as for the aforementioned mitral regurgitation, except its point of maximal intensity is in the right fourth intercostal space. Evaluation usually consisting of echocardiography is recommended in all horses with a murmur of grade four or more.

VSDs are associated with two murmurs – one on the left and the other on the right. The right-sided murmur is usually louder than the left and is caused by turbulent blood flowing through the defect in the interventricular septum. It is always loud and is loudest when the hole is small. It is a harsh, pansystolic murmur and crescendo-decrescendo or decrescendo in shape. Its point of maximal intensity is the fifth to fourth right intercostal space and it radiates ventrally. The left-sided murmur is associated with turbulent flow in the pulmonary artery and is usually holosystolic, with a blowing character and decrescendo shape, with a point of maximal intensity in the fourth left intercostal space.

It is not possible to discern from auscultation how large the defect is and whether it will cause problems in the future. Heart failure associated with VSDs has been recognised in animals up to five or six years of age. Evaluation involves echocardiography and includes Doppler evaluation to interrogate pressure differences between the two ventricles.

The most common dysrhythmias identified in the horse are second-degree atrioventricular block, which is usually physiological, and atrial fibrillation, which is pathological. Other physiological dysrhythmias include first-degree atrioventricular block, sinoatrial pause and arrest (Figure 5), and sinus dysrhythmia (although this may be associated with underlying respiratory disease at rest).

Other pathological dysrhythmias include supraventricular and ventricular premature depolarisations, supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia and third-degree atrioventricular block.

Second-degree atrioventricular block is usually a regularly irregular bradyarrhythmia, where horses have a regular number of unconducted beats, assuming their sympathetic tone doesn’t change. Occasionally, more than one consecutive beat is not conducted – this is called advanced second-degree atrioventricular block. Assuming this rhythm disappears at exercise, it is regarded as normal. Be aware, however, that this rhythm can return very quickly after cessation of exercise, despite not having been present at peak exercise. This small sub-group may, therefore, require exercising ECGs.

Sustained atrial fibrillation is the most common pathological bradyarrhythmia, usually seen in larger, athletic horses. It is most commonly idiopathic, but can be secondary to electrolyte derangements, mitral regurgitation resulting in an enlarged left atrium or to heart failure. Heart rate, unless in heart failure, is low or normal and results in an irregularly irregular rhythm.

There is no S4, a booming S1 and usually the third heart sound is audible (the heart sound more closely associated with the second heart sound). Jugular filling will be variable. At exercise, the rhythm will become more regular, so can be challenging to identify in some horses post-exercise, based on auscultation (Figure 1). These horses should, at a minimum, undergo a resting and exercising ECG. The need for the latter relates to a proportion of horses developing a rapid idioventricular response (Figure 6), which could predispose these animals to developing ventricular fibrillation at exercise.

Echocardiography may also be recommended for some cases. Swift treatment for idiopathic forms of atrial fibrillation have good to excellent results. Treatment options include quinidine gluconate via nasogastric tube and electrocardioversion. This is offered by several centres in the UK, including Rossdales Equine Hospital, which has performed the most electrocardioversions in the UK.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation can be more challenging to diagnose and treat, particularly if it only occurs during competitions. Diagnosis may be possible in the immediate post-competition phase or identified on exercising ECGs at home.Evaluation of blood electrolytes and fractional excretion of electrolytes can be valuable, as can measurement of serum cardiac troponin concentrations. Treatment will usually include rest and correction of any possible underlying abnormalities.

Supraventricular premature depolarisations are unlikely to be of importance regarding safety or performance (unless very frequent), but can predispose animals to developing atrial fibrillation.

Ventricular premature depolarisations (VPDs; Figure 7) at peak exercise, particularly when numerous or multiform, are a concern as these horses could develop into ventricular tachycardia (Figure 8) and then fibrillation.

The advent of affordable mobile phone-based apps (Figure 9) for recording ECGs has made obtaining a fast, horse-side diagnosis much easier. The electrodes, which are either attached to your mobile phone or held close to it, should be inserted under the triceps in a position where the heart would be loud and will record an ECG that can be saved and emailed as required.

Wetting the hair may be required. Optimal orientation is horse dependent – with most it works best held vertically.

Of concern on echocardiography are enlarged atria and ventricles, as these could predispose to rhythm disturbances at rest and exercise, enlarged pulmonary arteries secondary to mitral regurgitation, as these could result in pulmonary artery rupture, large VSDs (when compared with aortic size) and small pressure differences between left and right ventricles with VSDs, as these could predispose to reversal of blood flow (usually left to right).

Dysrhythmias of concern are VPDs at peak exercise and idioventricular responses at exercise secondary to atrial fibrillation.

Valvular disease is generally progressive in the horse. Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation generally progress slowly, although can be of concern in the younger horse, where their working life from diagnosis is longer.

Positively, murmurs associated with mitral valve prolapse usually do not result in cardiac modelling and progression over time and, thus, the prognosis is good. Aortic regurgitation will always progress and, probably, larger jet size and width may predispose to faster development.

When atrial fibrillation is found with no pathological underlying cause, conversion is successful in the majority of cases. However, risk factors remain in those animals (large atrial mass, high vagal tone and low heart rate) and they are, therefore, at increased risk of re-fibrillating in the future. Treatment and rest can be successful for management of supra-ventricular and ventricular premature depolarisations if no underlying cardiac changes are identified.

Attention to detail on auscultation can allow for likely differentiation of physiological and pathological disease, and identification of those animals that require further evaluation and treatment.