4 Aug 2020

Charlotte Easton-Jones describes how general practitioners can diagnose and treat respiratory problems in these patients.

Equine asthma syndrome is the new term for the conditions historically referred to as inflammatory airway disease and recurrent airway obstruction. The syndrome is triggered by inhalation of allergens and irritants, resulting in airway inflammation and mucus accumulation.

Mild to moderate equine asthma is more commonly seen in young horses presenting for poor performance or intermittent coughing that do not show clinical signs at rest. In contrast, severe equine asthma more frequently affects older horses that display clinical signs at rest, including coughing, exercise intolerance and increased respiratory rate.

Diagnosis is based on consistent clinical signs, excessive tracheal mucus on endoscopy and elevated inflammatory cells (usually neutrophils) on bronchoalveolar lavage cytology.

Treatment relies on a combination of environmental management and medication. Inhaled medications are more often used in the treatment of mild to moderate cases of equine asthma. Exclusion of an active infectious process is important before treating with immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids.

Equine asthma syndrome is the new umbrella term for the conditions historically referred to as inflammatory airway disease (IAD), recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), summer pasture‑associated obstructive pulmonary disease or heaves.

This is not the first time the name used to refer to this condition has changed. Prior to this, RAO was referred to as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – a term adopted from our human medicine counterparts to describe a range of progressive lung diseases, including asthma. This moniker was relinquished due to fears the use of this human term would cause confusion as the pathogenesis of equine RAO is different to that of human COPD.

Given the challenges for the busy equine practitioner of keeping up to date with the plethora of new equine veterinary literature, some frustration may arise at the decision to again change the terminology used to refer to this condition.

Despite the possible confusion for veterinarians and owners, the changes in terminology are a reflection of our increased knowledge and understanding of these conditions.

The most recent equine asthma terminology has been adopted as both diseases are characterised by airway inflammation and mucus accumulation. Similar to human asthma, equine asthma is triggered and exacerbated by the inhalation of dusts that contain allergens and irritants.

Despite horses with similar signs presenting with different disease severity, equine asthma should not be interpreted as a disease continuum. Put simply, horses with mild to moderate equine asthma do not necessarily develop severe equine asthma over time.

Semantics of official terminology aside, what is important is what developments have been made in the field of equine asthma, and how this may affect the diagnosis and treatment of equine respiratory problems.

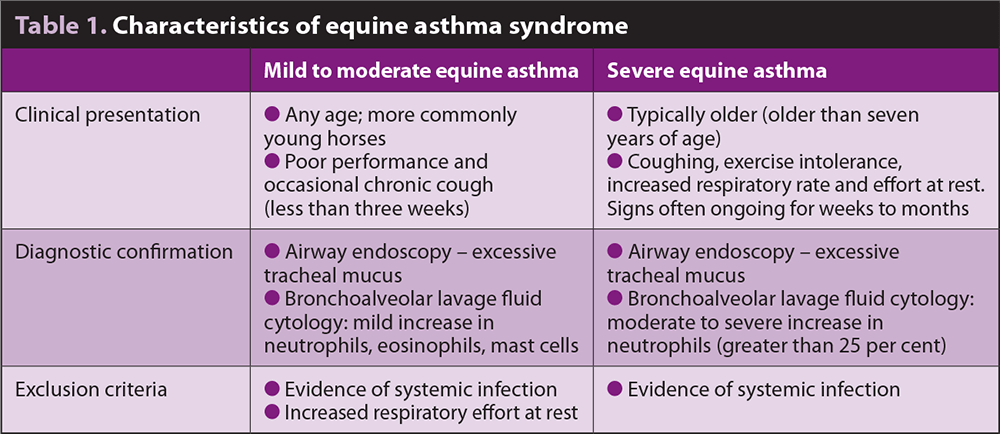

It remains helpful to think about equine asthma in terms of mild to moderate equine asthma (formerly IAD) and severe equine asthma (formerly RAO). These subclassifications have been retained in the recently revised American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement on inflammatory airway disease1, and the differences are summarised in Table 1.

Mild to moderate equine asthma is more commonly seen in young horses presenting for poor performance or chronic coughing that do not show clinical signs at rest, versus the more severe asthma cases that frequently affect older horses in which, due to the severity of the condition, clinical signs are noted at rest.

Horses with mild equine asthma typically present with signs of poor performance or chronic coughing (more than three weeks in duration).

Poor performance can be caused by an abundance of conditions; therefore, ruling out other causes – such as upper airway obstruction, and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal problems – is important.

Severe equine asthma cases display marked lower airway inflammation and obstruction. Clinical signs noted include coughing, increased respiratory effort at rest and exercise intolerance. Wheezes are frequently heard in the caudodorsal lung fields on auscultation.

Previous research has identified a five times greater incidence of severe equine asthma in the offspring of affected horses compared with offspring from unaffected parents, suggesting genetic predisposition is a factor in disease pathogenesis2,3.

Horses with equine asthma have reversible bronchospasm and should, therefore, respond to a bronchodilator test (atropine or N-butylscopolammonium bromide). If a significant improvement in respiratory rate and effort is noted within the 15 minutes following a bronchodilator test, this suggests bronchospasm is contributing to clinical signs.

Atropine: the atropine response test involves administering 0.02mg/kg atropine IV (5mg to 7mg in a 450kg horse).

N-butylscopolammonium bromide: 0.3mg/kg IV, duration 30 minutes.

Ruling out an infectious cause of respiratory disease is important in these cases – particularly given that treatment frequently involves immunosuppressive corticosteroids. Horses with equine asthma are usually afebrile with a normal haematology.

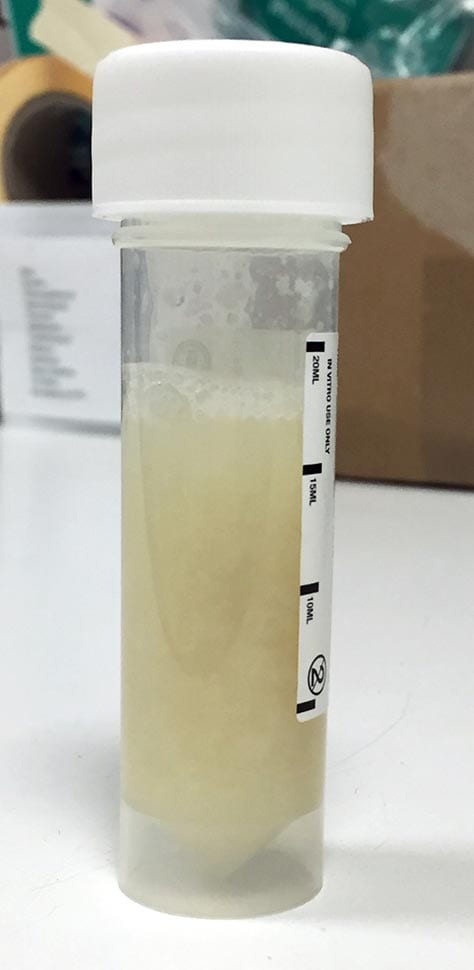

Tracheal wash cytology normally displays neutrophilic inflammation, but no evidence of toxic or degenerative changes to neutrophils exists. Tracheal wash culture can be further performed to rule out an underlying or secondary bacterial or fungal infection (Figure 1).

Nasopharyngeal swabs can be submitted for respiratory PCR panels to exclude viral causes of respiratory disease, such as equine influenza and equine herpesviruses.

Upper airway endoscopy reveals excess mucus in both mild to moderate asthma and severe asthma cases (Figure 2).

A mucus scoring system has been described – with a grade greater than or equal to two significant in racehorses, and greater than or equal to three significant in pleasure and sports horses1,4.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) cytology is central to the diagnosis of equine asthma, as well as helping to differentiate mild to moderate equine asthma from severe equine asthma.

Horses with mild to moderate equine asthma show mild increases in BALF neutrophils (greater than 10% and lower than 25%), eosinophils (greater than 1%) and/or mast cells (greater than 2%).

In comparison, horses with severe equine asthma have a more severe neutrophilic inflammation on BALF (greater than 25% neutrophils; Figure 3).

Thoracic radiographs are supportive and can help rule out an infectious cause of respiratory disease, but are not definitive. Radiographs often have an increased bronchial pattern and hyperinflation can be seen in severe cases.

Pulmonary function testing has been used to diagnose equine asthma, although this requires specialist equipment and is, therefore, restricted to research or referral centres.

Serum acute phase proteins (serum amyloid A, haptoglobin and C‑reactive protein) have been investigated in horses with mild equine asthma and do not appear to correspond to abnormal bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytology or clinical signs5.

Treatment of equine asthma can be divided into medications and environmental management.

Medications are often essential to combat an acute respiratory crisis, but the cornerstone to long-term treatment and management of equine asthma remains environmental changes to remove the inciting dust and allergens. Despite the challenges of convincing reluctant owners to alter their management strategies, this is essential as medications alone are insufficient to manage the condition.

Certain medications, such as bronchodilators, may actually be detrimental if used in isolation.

Decreasing bronchospasm without improving the environment can lead to increased inhalation of allergens into the lung, further exacerbating the condition.

Environmental management is centred around reducing the exposure to airborne dust and moulds. The following general management changes are recommended6,7:

Use of “low dust” bedding (such as dust-extracted shavings, cardboard/paper) and feedstuffs. Feed has been shown to be the largest contributor to respirable dust, with simple measures such as soaking hay reducing respirable dust by 60%8. Horses that are fed steamed hay have also been shown to have a decreased likelihood of being diagnosed with mild to moderate equine asthma9.

Hay can, alternatively, be replaced with haylage or a complete pelleted diet.

For most equine asthma cases, maximising turnout helps to reduce exposure to respirable articles.

Feeding hay from the ground is recommended, as hay fed from a hay net has four times the amount of exposure to respirable dust10.

Improving ventilation to the stables or barn.

Removing horses from the stables when mucking out is occurring.

Supplementation of the diet with omega-3 fatty acids – in particular docosahexaenoic acid (1.5g/day) – when combined with a low dust diet has been shown to produce a faster clinical improvement in horses with equine asthma when compared to a low dust diet alone and control horses11.

Equine asthma syndrome is characterised by neutrophils accumulating in large numbers in the lower airways.

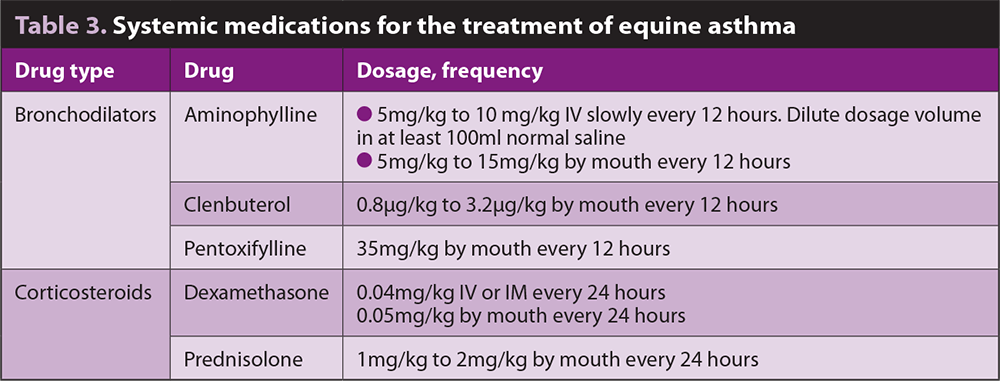

Corticosteroids continue to be key in the control of the lower airway inflammation in equine asthma cases. Given the possible side effects of systemic medications such as corticosteroids, the use of inhaled medications has been increasing.

Inhaled medications are more frequently used in the treatment of mild to moderate cases of equine asthma where airway inflammation and clinical signs are less severe (Table 2).

Systemic treatment improves clinical signs and lung function more rapidly, and, therefore, is more commonly used in horses with severe asthma signs – particularly those that present in an acute crisis.

Bronchodilators have a shorter period of action than corticosteroids, but are often used concurrently to reduce bronchospasm and coughing. The enhanced mucociliary clearance from bronchodilator use may also help reduce clinical signs.

Care must be taken with prolonged use of bronchodilators, such as beta-2 agonists, as their effectiveness decreases over time12.

Administration of inhaled medications requires the owner to buy a nebuliser or inhaler device (Figure 4). Numerous companies produce equine inhalers or nebulisers and the vast majority of horses can be trained to accept inhaled treatments.

The three categories of inhaled drugs commonly used to treat airway inflammation include corticosteroids, bronchodilators and mast cell stabilisers.

Inhaled beclomethasone and fluticasone can be administered via inhalers or a nebuliser device.

It is generally believed the systemic side effects are fewer with inhaled corticosteroids than systemic corticosteroids, although further data is needed. Inhaled corticosteroids may, therefore, be useful in horses at a higher risk of side effects, such as those with equine metabolic syndrome or laminitis.

One study revealed adrenal suppression following treatment with inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate, indicating systemic effects are still possible13,14. Another study revealed the presence of a fluticasone propionate metabolite in the blood and urine after the drug was inhaled at therapeutic doses15.

This information is particularly important for competition horses where drug withdrawal times are a consideration.

Conflicting evidence exists concerning whether the nebulisation of dexamethasone sodium phosphate is an effective treatment for equine asthma. One study reported low systemic bioavailability and a lack of suppression of the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal axis after nebulisation of dexamethasone to healthy horses16. However, when nebulisation of dexamethasone was compared to oral administration in a recent study, a lack of improvement occurred in lung function and evidence existed of hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal axis suppression in horses with severe asthma17.

Other novel inhaled corticosteroids recently investigated include budesonide18 and ciclesonide19. This year the Aservo EquiHaler (Boehringer Ingelheim), containing the corticosteroid ciclesonide, has become the first inhalant therapy approved by the European Commission for use in horses with severe equine asthma. It is not currently available to buy, but is expected to be released later this year.

The initial experimental study of this product displayed similar responses in airway function to dexamethasone (0.06mg/kg once daily) and no evidence of systemic effects19.

Inhaled bronchodilators include albuterol, ipratropium bromide, salbutamol and salmeterol. Mast cell stabilisers, such as sodium cromoglycate, can be used in young performance horses with lower airway inflammation associated with high mast cell counts on BAL20.

Recent studies have suggested even mild equine asthma can impact a horse’s performance and, therefore, warrants treatment.

Environmental management remains the key to controlling the condition, but medications are frequently required to overcome an acute crisis, and facilitate treatment and management of the syndrome.