20 Feb 2024

Little used to be known about equine dentistry, but things have changed in the past two decades. The author looks at some of the common disorders seen in horses, and discusses how they can be diagnosed and managed.

Equine dentistry used to be a poorly understood and underappreciated field in veterinary medicine. In the past 20 years, significant work has been done to advance this area, and many older procedures have been scrutinised as to their merit in preserving and prolonging dental health care (wolf tooth extraction, incisor and cheek tooth levelling, and bit seating, for example).

Equine dental disease is one of the most common diseases seen by general practitioners across Europe, the UK and the US. This article is aimed at highlighting common disorders seen in our equine patients, and discusses management, diagnosis and treatment.

• Wear abnormalities

Wear abnormalities include “smile”/”frown” (Figure 1a), which reduce the lateral excursion and grinding of the cheek teeth. Neglecting these will lead to significant masticatory problems.

Crib biters (Figure 1b) cause considerable abnormal wear to the occlusal and rostral surfaces of their incisors. These horses are at a higher risk of developing colic during their lifetime (a 35% chance), with epiploic foramen entrapments 72 times more likely to occur.

Another problem is “slant mouth” (Figure 1c), which results in chewing in one direction. It is important this is spotted early because horses can develop secondary to severe cheek teeth problems and craniofacial abnormalities.

• Overjet and overbite

Overjet (the rostral projection of upper incisors) and overbite (where the upper incisors grow down in front of the lower incisors) can lead to wear disorders of both the incisors and cheek teeth, which are seen as overgrowths in the maxillary 06s and mandibular 11s. In older animals, the reduced wear on the central incisors (01s) leads to a “smile”.

• Equine odontoclastic tooth resorption and hypercementosis

The condition of equine odontoclastic tooth resorption and hypercementosis (EOTRH) is a progressive, destructive and painful disease resulting in inflammation of the pulp, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone (Figure 1d). This disease is seen in mature animals and most commonly affects the incisors, but can also involve the canines and cheek teeth. Horses will be reluctant or refuse to bite into apples or carrots.

Wolf teeth are small, vestigial teeth (around 1cm to 3cm long) commonly found on the maxilla (less common on the mandible). They erupt between 6 to 18 months old. Historically, these have been implicated in behavioural and bitting problems, and removed, but this has been questioned in the past few years.

• Sharp enamel points

Sharp enamel points (SEPs) naturally occur in horses due to the orientation of the maxillary and mandibular arcades. The maxillary arcade is wider than the mandibular arcade, which results in the development of SEPs on the buccal side of the maxillary cheek teeth and lingual aspect of the mandibular cheek teeth.

• Caps

Retained deciduous cheek teeth (known as caps) are typically seen between two and five years. If they are loose or partially retained, they can cause pain, quidding and bitting issues. Horses with loose caps may be seen playing with their tongue a lot. The practice of removing these at a set age is strongly discouraged, as premature removal of the cap is painful and exposes the underdeveloped permanent cheek tooth, which ultimately can predispose the tooth to infundibular caries, apical infection and/or fracture.

• Pulp horn exposure

Pulp horn exposure (PHE) can lead to ascending infection in the tooth, requiring removal if not caught early enough.

• Secondary sinusitis

Due to periapical infection of the cheek tooth, secondary sinusitis has multiple causes, including ascending infection through PHE, infundibular caries, fractures or anachoreses. Horses typically have a malodorous breath, plus or minus nasal discharge if the tooth is associated with the sinuses, or hard, bony swellings over the root of the affected tooth.

• Smooth mouth

Seen in the older equine population, smooth mouth (Figure 2) is where the cheek teeth enamel has mostly worn away. The exposed dentine and cementum are softer, so they become smooth and are no longer able to grind fibrous material.

• Displaced cheek teeth

Usually involving the 09s and 10s, displaced cheek teeth can lead to overgrowths, diastema, quidding and food packing. Severe cases can lead to osteomyelitis/sinusitis, which tend to be a developmental condition secondary to overcrowding (seen in miniatures).

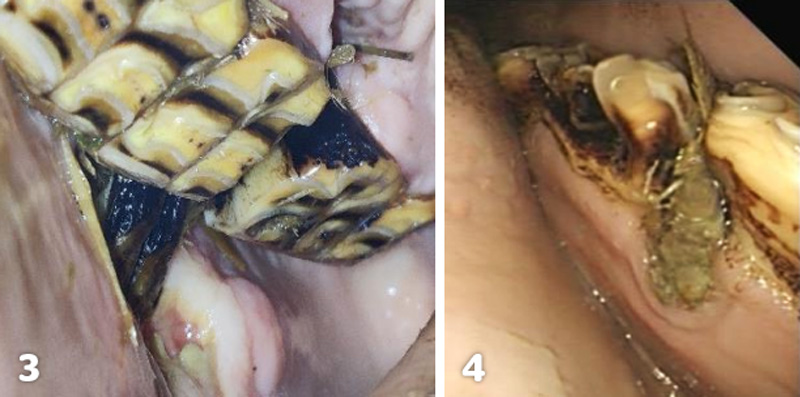

• Idiopathic lateral “slab” fractures

Common and typically affecting the maxillary 09s, idiopathic lateral “slab” fracturing occurs through pulp horns 1 and 2. Food impacts into the fracture, displacing the smaller fragment buccally (Figure 3), resulting in pain, quidding and the favouring of one side. These are unlikely to cause sinusitis, as the pulp horn usually seals itself off, so the tooth remains vital. Removal of the fractured fragment is usually enough to resolve clinical signs. Removal of the entire tooth is necessary where a PHE is on the remaining portion.

• Midline sagittal fractures

Secondary to advanced infundibular caries, midline sagittal fractures also typically affect the maxillary 09s, but are less common than slab fractures, and are associated with secondary sinusitis.

• Diastemata

A diastema (Figure 4) is the most common cause of painful dental disease in horses. Diastemata are the spaces between the occlusal aspect of adjacent teeth.

In severe cases, valve diastemata (narrow at the occlusal surface and wider at the gingiva) result in food trapping in the space, and the trapped food getting pushed deeper into the gingiva over time. These result in considerable pain, which can be seen clinically by quidding (76% of cases), weight loss (33% of cases) and halitosis (11% of cases). The vast majority are found in the mandibular arcade (90%).

• Caries lesions

A progressive demineralisation of dental tissues, caries lesions develop from acid produced by bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates. They most commonly affect the cheek tooth, and are named based on their location (peripheral, infundibular and occlusal). Infundibular caries (graded 1 to 4), if severe, will coalesce and can cause a midline/sagittal fracture of the cheek tooth.

Routine dental examinations should be carried out by a vet or qualified equine dental technician. Dental exams are typically performed every 6 to 12 months.

Management of cases will largely depend on the animal’s age, use and dental pathology; time and financial implications should also be taken into consideration when discussing management of dental disease, as these will require lifetime care. Dietary management is key to preventing and managing many dental diseases.

An accurate history is required to help identify any underlying issues prior to an exam, such as:

The importance of an extra-oral exam cannot be overstated, and should cover the following:

An intra-oral exam cannot be done without a full mouth speculum, with the following:

Radiographs are required for any suspected periapical cheek tooth infection, draining tracts or swellings of the head.

However, in the early stage of periapical infection, changes may be subtle or not visible.

Ultrasound is most useful in cases of soft tissue swelling of the head or investigation of injury to the bars of the mouth (rectal probe).

Upper respiratory tract endoscopy can be performed, but vets should check the drainage angle for any discharge here.

Sinoscopy, which can be useful in diagnosing diseases of the sinus, tends to be done alongside treatment

CT is the gold standard for diagnostic imaging of the head and has greater diagnostic accuracy than radiographs. It also allows for earlier diagnosis of lesions and aids in surgical planning in cases such as sinus masses or fractures of the skull.

Incisor wear abnormalities require management of the underlying issue – for example, cheek teeth abnormalities, temporohyoid osteoarthropathy, temporomandibular joint disease and reduce cribbing. Incisor odontoplasty may be required in severe cases but as an adjunct to treating the causative issue and should never be done as a sole treatment

With diastemata, the diet should be conservatively adjusted from long-fibre food to grass or a finely chopped diet, removing the impacted feed. This is usually a short-term fix.

Most cases require widening of the diastema to 4mm to 6mm at the occlusal surface.

The specialised veterinary procedure has a prognosis of complete resolution of 50% and partial as 20%. In a subset of cases where widening fails, extraction of the tooth is required

SEPs, step overgrowths, wave mouth, shear mouth or parrot mouth can be managed with reducing the overgrowths (hand or power float). It is important not to remove too much of the tooth in one sitting, as this can lead to iatrogenic PHE. Managing these cases may require visits every 10 to 12 weeks until corrected.

Smooth mouth can be managed with special diets aimed at older horses. Options include chopped hay, hay cubes or pellets, and beet pulp/forage-based complete feeds.

Endodontic therapy can be performed in infundibular caries and PHE cases, but requires good case selection.

Oral extraction of cheek teeth is required for diastemata that fail to respond to widening, periapical infection of cheek teeth (PHE or severe infundibular caries) or displaced cheek teeth causing clinical disease.

Bit-induced lesions require removal of the sequestra/exostoses on the mandible. Following surgery, the use of a bitless bridle for four to six weeks is encouraged.

Equine dentistry has advanced significantly in the past 20 years, with the focus on early intervention to improve and preserve dental health care. A thorough exam of the horse (intra and extra-oral exams) to detect early stages of dental pathology and appropriate treatment is fundamental to this.