22 Oct 2018

Nicola Menzies-Gow looks into drug therapy and managing clinical signs of this disease in horses to provide years of good quality life.

Figure 1. A 21-year-old pony mare with regional hypertrichosis.

Equine pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease with loss of dopaminergic (inhibitory) input to the melanotropes of the pituitary pars intermedia, which appears to be associated with localised oxidative stress and abnormal protein (α−synuclein) accumulation. However, the exact cause remains unknown.

The consequent dysfunction of this region results in hyperplasia of this area of the gland and overproduction of pars intermedia-derived hormones. Eventually the area undergoes adenomatous change.

The condition is seen in older animals; the average age in retrospective case series ranges from 18 to 23 years1-4. No predilection for breed or sex exists, but ponies are more often affected than horses in some studies2-4. In one survey, 21% of horses aged more than 15 years had endocrine changes consistent with PPID5 and, in a second, clinical signs consistent with PPID were documented in nearly 40% of horses more than 30 years old6. However, it should be noted the disease is recognised in animals younger than this, with the youngest reported case being in a seven-year-old animal7.

The clinical signs associated with PPID can be roughly divided into those seen early in the disease and those linked with advanced disease. Early signs include decreased athletic performance, change in attitude/lethargy, delayed haircoat shedding, regional hypertrichosis (Figure 1), change in body conformation, regional adiposity and laminitis. Late signs include lethargy, generalised hypertrichosis, skeletal muscle atrophy, hyperhidrosis, polyuria/polydipsia, recurrent infections, infertility and laminitis.

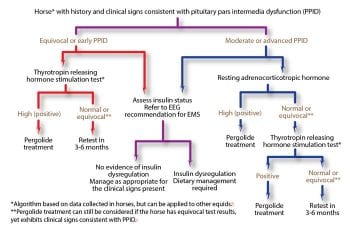

Diagnosis of PPID is based on the signalment, clinical signs and further diagnostic test results. No ideal further diagnostic test for equine PPID exists; however, plasma basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) concentrations and the ACTH response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone are thought to be the most appropriate tests available (Figure 2). In addition, it is recommended tests to assess for insulin dysregulation (ID) are concurrently employed, as ID occurs in a subset of animals with PPID5 and appears to be associated with an increased risk of laminitis8 and a worse prognosis9. Appropriate tests for ID include measurement of basal serum insulin concentration, an oral sugar or glucose test and the insulin response test.

PPID is a slowly progressive, lifelong condition. The aim of treatment is not to cure the condition, but to increase the patient’s quality of life by reducing the clinical signs – including those with the potential to be life-threatening.

While the benefits of treating a laminitic case with a definitive diagnosis of PPID are clear, in cases with clinical signs that are not life-threatening, the decision to specifically treat the PPID is less clear-cut as no evidence has been published to date demonstrating pergolide prevents laminitis or the progression of PPID.

Some argue pharmacologic management in such cases is appropriate as it is should be considered to be prophylactic treatment of a condition that may threaten health in the future. However, the decision should be made following discussion with the owner, taking into account the financial implications and potential adverse effects of lifelong treatment.

Laminitis is the most common clinical sign that will enforce the use of pharmacological agents to help control the disease. Where specific medical therapy is used, two drug types are available:

Dopamine agonists replace the lost dopaminergic inhibition to the pars intermedia and so reduce hormone production. Interaction with D2 receptors inhibits the excessive hormone secretion and is, therefore, associated with improvement in clinical signs. It has not been determined whether pergolide treatment also inhibits the development of pituitary hyperplasia or reduces the size of pituitary adenomas, but these beneficial effects are plausible.

Pergolide is available as a licensed product in the UK for the treatment of PPID in horses (Prascend: Boehringer Ingelheim). It is reported to be effective in 65% to 80% of cases4,10. The initial dose is 2μg/kg po SID for four to six weeks (0.5mg for a 250kg pony and 1mg for a 500kg horse)11. The dose is increased in increments of 1μg/kg/day with reassessment every four to six weeks to a maximum of 6μg/kg/day if the clinical or laboratory response is not adequate, or decreased slowly at four to six-week intervals to the lowest apparently effective dose12.

Side effects include anorexia, diarrhoea, depression and colic13; however, only anorexia and depression are reported with any frequency14-16. If signs of dose intolerance develop, treatment should be stopped for two to three days and then reinstituted at half the previous dose for the first four days or by administering half the dose morning and evening11. The total daily dose may then be gradually increased until the desired clinical effect is achieved, increasing in 0.5mg increments every two to four weeks. Contraindications to using pergolide include animals with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or other ergot derivatives, animals less than two years old, and pregnant or lactating animals.

PPID is a slowly progressive disease and the amount of pergolide required to control the symptoms is likely to increase as the horse ages. In addition, a normal physiologic increase in hormone production by the pituitary gland occurs in the autumn. Some horses only seem to need pergolide during this seasonal rise in the early stages of the disease; alternatively, some horses appear to need an increased dose of pergolide during this seasonal rise.

Serotonin antagonists decrease the serotonin-induced stimulation to the pars intermedia. Cyproheptadine (0.25mg/kg to 0.5mg/kg po SID or BID) has been recommended for the treatment of PPID and reported to be effective in 28% to 60% of cases4,10,17.

However, similar improvements were achieved with improved nutrition, preventive care and management alone14. In addition, pergolide has been shown to be more effective than cyproheptadine for the medical treatment of PPID4. Thus, cyproheptadine monotherapy is no longer advocated for the treatment of equine PPID; however, it can be used in addition to pergolide in refractory cases.

Three possible monitoring strategies exist:

The laboratory response to pergolide therapy can be monitored. Of the horses receiving 1.5mg pergolide SID that displayed an improvement in their ACTH concentrations, 52% to 72% showed an improvement within 7 days; 62% to 82% within 14 days and 74% to 96% within 4 weeks. Thus, it is proposed the best practice for monitoring PPID includes measurement of plasma ACTH concentrations 30 days after pergolide treatment is started18.

If it has not returned to within the seasonally adjusted reference range at this time, the dose should be incrementally increased (by 1μg/kg to 2μg/kg per day) at four-week intervals until it does. Once a suitable dose has been found, plasma ACTH concentrations should subsequently be measured annually, or some suggest biannually in the autumn and spring, and the pergolide dose adjusted to maintain plasma ACTH concentrations within the reference range.

Some horses have very high plasma ACTH concentrations and, in these cases, it may not be possible to return concentrations to normal11, thus, other approaches must be considered. Ideally, the dose should be incrementally increased to try to return plasma ACTH concentrations to within the reference range up to a maximum dose of 5mg SID. If finances preclude this approach, an affordable dose that elicits a significant decrease in plasma ACTH concentration, even if concentrations remain above the reference range, should then be used18.

Alternatively, the clinical response to treatment can be monitored. Increased alertness and activity, and decreased drinking and urination, are reported to improve first, within 30 days of starting treatment. Other signs, such as hypertrichosis and skeletal muscle atrophy, may take up to 12 months to improve.

A period of two months is required before conclusions should be drawn about changes in the clinical signs; the dose of pergolide can then be altered according to how well the clinical signs improve. Once the disease is controlled, a clinical assessment should be performed every six months to monitor treatment success and the pergolide dose adjusted to maintain a clinical response.

Finally and ideally, the laboratory response can be assessed in conjunction with the clinical response. If the laboratory response is within the reference range at the recheck, but a recurrence or development of new problems – such as laminitis, bacterial infection or weight loss – have occurred, the horse should be reassessed for additional medical problems, including insulin dysregulation, before assuming an increase in pergolide dosage is required.

If an inadequate laboratory response is seen with a good clinical response, the dosage can be held at the same level or be increased, according to the vet’s preference and in consultation with the owner. This may be observed more commonly when testing is performed in the autumn.

If an inadequate laboratory response is seen in conjunction with a poor clinical response, the dose should be incrementally increased (by 1μg/kg/day-2μg/kg/day) at four-week intervals until it does or a maximal dose is reached.

Alternative therapies that have been investigated include an aqueous extract of the herb Vitex agnus-castus (chasteberry), which is reported to contain compounds (diterpenoids) that stimulate dopamine D2 receptor activity and inhibit different opioid receptors. However, in the only published study, it failed to resolve clinical signs or improve diagnostic test results in 14 horses with PPID19.

If an owner elects not to treat PPID specifically, the clinical signs can be managed individually:

Clipping excess hair will help with hypertrichosis and also help with hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) if it is secondary to the excess hair.

When secondary infections occur, the specific treatment required will depend on their nature. The most commonly reported of these are parasites, sinusitis, skin infections, respiratory tract infections and hoof abscesses20-22.

Gastrointestinal parasitism will require appropriate anthelmintic therapy, depending on the specific parasite involved. Sinusitis should be treated initially with antibiotic therapy and appropriate adjunctive management changes, such as feeding from the floor to encourage sinus drainage. If this is not successful, further therapy, such as sinuscopic lavage and standing sinusotomy, may be required. Dermatological and respiratory bacterial infections will require appropriate antibiotic therapy based on bacteriology results.

The diet should ideally be analysed by a nutritionist. Feed selection should be based on body condition score and evidence of insulin dysregulation. Some horses with PPID are lean and have normal insulin status; senior feeds and pasture grazing are appropriate in these cases. Obese horses should be fed a lower energy diet and exercised, and those with ID require lower non-structural carbohydrate feeds and limited access to pasture. Feed requirements of aged horses, especially those with PPID, may change over time, and monitoring of body condition score is recommended.

Dietary supplements have been suggested for the management of PPID, but to date, scientific evidence for their efficacy is lacking.

Laminitic episodes in animals with PPID should be treated in the same way as equine metabolic syndrome-associated laminitis or non-endocrinopathic laminitis. Therapy should be aimed at providing analgesia and foot support. NSAIDs given either orally or intravenously are the first choice for analgesia, but no evidence exists to suggest any one specific NSAID is superior23. If they do not provide sufficient pain relief, opiates can additionally be used, such as butorphanol, pethidine, morphine and fentanyl patches.

Supporting the foot is an essential part in the management of acute laminitis (Figure 3). The horse naturally adopts a stance that bears most of its weight over the caudal part of the foot, rather than the painful toe region. Additional support should be supplied to this region of the foot to provide pain relief and minimise the mechanical forces on the laminae, and hence laminar tearing and pedal bone movement.

The simplest method is to increase the depth of the bedding – ensuring the bedding extends to the door where the horse will spend a significant proportion of its day standing. Shavings, sand, peat or hemp-based products are best as they pack beneath the feet better than straw or paper.

Extra support can be applied directly to the caudal two-thirds of the foot itself. This can be done in a variety of ways, which can be broadly divided into frog-only supports and combined frog and sole supports.

A frog-only support can be achieved using rolled-up bandaging material of the same length as the frog, placed along the length of the frog and secured in place with adhesive tape. Alternatively, a commercially available product, such as frog supports, can be used. Combined frog and sole support can be provided using, for example, dental impression material moulded to the contours of the caudal two-thirds of the foot or Styrofoam pads that are crushed by the weight of the horse. No evidence exists to suggest any one foot support method is superior23.

Scientific evidence supports the use of vasoconstrictor therapy in the form of digital hypothermia or cryotherapy in the treatment of sepsis-associated laminitis. It has provided a protective effect clinically and histologically when employed prior to the onset of the disease process24,25, and after the onset of lameness26 in experimental models of laminitis, and decreased the incidence of laminitis in horses with colitis27. However, the effectiveness of digital cryotherapy in endocrinopathic laminitis has not yet been evaluated.

Since the exact cause of equine PPID remains unknown, no methods exist to prevent it.

The disease requires lifelong management and lifelong drug therapy as all the available drugs will only help to control the clinical signs, but not result in a cure. Two studies have evaluated short-term survival in horses with PPID. In one study, low serum insulin concentration before treatment was significantly associated with improved short-term survival up to one to two years9. In a second study, comparison of plasma ACTH concentrations at baseline with those a median of two months after treatment were found to be helpful when monitoring PPID treatment in 42 horses, but improvement in clinical signs was considered the most important indicator of prognosis10.

Long-term survival has been evaluated once. The clinical signs and clinicopathologic data were not associated with survival; however, 50% of horses were alive 4.6 years after diagnosis20. Thus, many horses can continue to have a good quality of life for a number of years.