7 Jan 2019

Andy Durham takes a look at equine skin diseases, focusing on how to differentiate and treat them effectively.

A common feeling of unease exists in practice when dealing with equine skin diseases, which can be dramatically improved by developing a routine to be followed in each case presented (Panel 1).

1. History taking.

2. Examination and description of skin lesions.

3. Categorisation.

4. Form list of differential diagnoses.

5. Select further diagnostic aids.

6. Achieve probable diagnosis.

7. Select appropriate treatment.

8. Review response to treatment.

Pattern recognition is a key step in the examination of skin disease cases, such that each case is placed into one (or more) of seven categories that best describes the most prominent feature of the condition (Panel 2). This important step allows the clinician to focus on a list of common (and less common) differential diagnoses known to exhibit the pattern of the selected category.

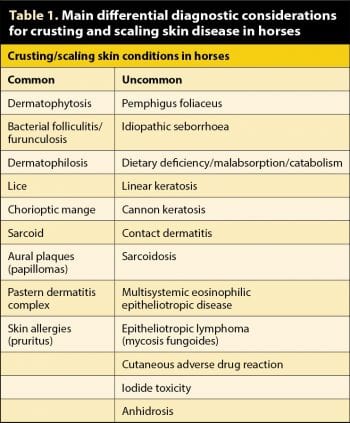

Scaling and crusting is one of the common patterns of equine skin disease and is, therefore, challenging due to numerous possible causes as listed in Table 1.

Scale reflects accumulation of many loose cornified fragments of skin, generally due to skin irritation and inflammatory insult, while crust (scab) is a dry, solid adherent mass having resulted from the drying of accumulated exudates, pus, serum and blood, and also usually reflects underlying skin inflammation.

This article will discuss some of the most common conditions that present with crusting and scaling in equine practice (Table 1).

Many causes of crusting and scaling may look remarkably similar (both grossly and histopathologically) as the skin reacts similarly to a range of causal insults. These will then require consideration of historical/environmental information, close examination and further diagnostic samples to be collected to make a specific diagnosis.

Scaling and crusting skin disease should initially focus on infective causes, with further diagnostic aids of swabs and plucks submitted for bacteriology and mycology, with biopsy being used where simple infectious dermatitis is ruled out or considered unlikely.

The initial aim of examination should simply be to place the case into one of these categories:

1. Altered sensation (pruritus or pain).

2. Lumps and bumps (papules, nodules, plaques, masses, wheals).

3. Dry scaling and crusting.

4. Hair loss (alopecia, hypotrichosis) or changes in hair quality.

5. Pigmentary changes (macules and patches).

6. Moist exudative skin diseases.

7. Skin disease as part of a wider systemic disorder.

Following a specific diagnosis, specific therapy can then be applied; or less ideally, where diagnostic options are limited by owner compliance and budget, then perhaps empirical therapy covering a few of the most common differential diagnoses might be employed.

A few scaling and crusting skin lesions may have a characteristic gross appearance allowing a fairly confident clinical diagnosis (for example – aural plaques, insect bite hypersensitivity, linear keratosis, cannon keratosis and sarcoidosis; Figures 1 to 3).

Some conditions may be painful, such as staphylococcal dermatitis or pemphigus foliaceus. Others may have characteristic distributions, such as coronary bands or mucocutaneous junctions, which immediately allows consideration of a restricted list of differential diagnoses (Panel 3 and Panel 4).

Thought should always be given to the possibility of skin disease as part of a multisystemic disorder if skin lesions are extensive or exaggerated or if the horse is at all unwell (Panel 5; Figure 4).

As scaling results from skin irritation, and crusting may result from self-trauma, most causes of pruritus may result in scaling and crusting, and it is diagnostically important to determine whether this key clinical sign is also present (Panel 6).

Depigmentation may have a primary association with certain rare crusting skin diseases, such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and might more commonly follow on from crusting skin disease, where skin disease and inflammation affects the deeper dermis.

Dermatophilus congolensis is an actinomycete bacterium commonly isolated from equine skin and becomes pathogenic when introduced into skin that is chronically wet, irritated or abraded. Wetting leads to the release of infective zoospores from surface carriers and these may be transmitted between horses by direct contact or fomites (rugs, flies, brushes).

Dermatophilosis is usually a winter-time problem due to the combination of rain and a thick coat leading to multiple dorsal crusts (“rainscald” lesions; Figure 5) although it may occur at any time of year – for example in crusting and scaling pastern dermatitis or photodermatitis lesions on the muzzle. Typical multifocal dorsal crusts of rainscald are usually felt more easily than they are seen, which perhaps facilitates their unnoticed development in field horses. Easy removal of hairs with an adherent circular crust (“paintbrush”) is often considered pathognomonic.

Maceration of crusts and gram staining reveals double chains of cocci (“railroad track”). Successful treatment requires dry conditions, while rugging is frequently insufficient once the disease has developed. Removal of crusts followed by antibacterial washes (for example, ethyl lactate or benzoyl peroxide) and antimicrobial creams (if a small area is affected) hastens recovery.

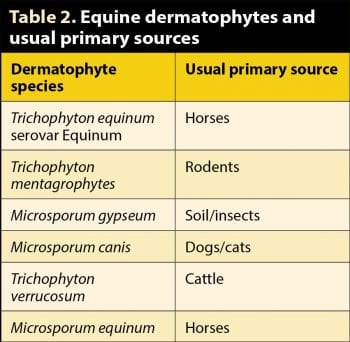

Infection with Trichophyton equinum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton verrucosum and Microsporum equinum are the most common causes of dermatophytosis in horses. Others less frequently isolated include Microsporum gypseum and Microsporum canis. Direct contact or, more commonly, fomites (for example, stables, fence posts, transport, tack, brushes), are implicated in spread.

Durable cell-mediated immune resistance may follow infection and, consequently, ringworm outbreaks are most commonly associated with naive young horses or new arrivals. However, reinfections do sometimes occur and this may be due to waning immunity, a different dermatophyte species, overwhelming challenge or previous prompt, effective treatment before an adequate immune response had been mounted.

Crusting/scaling coronary band disease:

The incidence in an outbreak varies depending on the dermatophyte species involved and the immune status of the exposed horses. An effective vaccine has been developed and used in eastern Europe.

The incubation period is usually about a week. Typically, multifocal sites of scaling and alopecia develop that are usually associated with small, raised papules, although well-demarcated, flat, alopecic areas may also be seen (Figure 6).

Mild to moderate sensitivity is common in the early stages, but very rarely pruritus (unlike human disease). Significant pain may reflect co-infection with staphylococci. Tack-related sites are most commonly affected, such as the lower girth area, lateral neck, face and lateral thorax, although other areas can be affected.

When classical bilateral scaling and crusting lesions are seen in the girth area one should assume ringworm is the cause unless proven otherwise. Multifocal scaling papules elsewhere are also highly suggestive. Differential diagnosis may be more difficult in cases where the lesions are unremarkable, flat alopecic areas, secondarily infected or oedematous.

The best diagnostic samples are stubbly and broken hairs plucked from the periphery of the most recent lesions following light cleansing with an alcohol swab to kill bacterial contaminants. Plucks should be stored in paper envelopes rather than sealed containers, which may provide a favourable humid environment for contaminants to grow. The plucked hair sample can be examined microscopically after clearing in warm 10% to 20% potassium hydroxide (Figure 7).

Crusting/scaling skin disease with mucocutaneous junctional lesions:

Negative or equivocal samples can be cultured either on dermatophyte test medium (DTM) at room temperature or on Sabouraud’s agar at 37°C. Frequent observation of DTM culture is essential and a red colour change within 24 hours of appearance of a dry white or beige colony is suggestive of a dermatophyte. Most dermatophytes grow within a week, but the culture should be left for two weeks.

Sabouraud’s agar encourages far more vigorous and successful growth of dermatophytes compared with DTM, and also allows specific identification, which might provide information on the source of infection in recurrent outbreaks (Table 2). Deep red-brown pigmentation of the underside of the colony is suggestive of the most common equine dermatophyte, T equinum serovar Equinum (Figure 8).

Contrary to popular myth, addition of niacin (or multivitamin solution) to dermatophyte culture media does not improve growth of T equinum serovar Equinum and is unnecessary.

Recently, a novel qPCR assay has been developed at the Liphook Equine Hospital Laboratory, which enables the diagnosis of equine dermatophytosis within two hours, and makes attempted microscopic examination and culture unnecessary. In addition to the time savings, the qPCR assay has been shown to be more than 40 times more sensitive than culture on Sabouraud’s agar (OR=44.9, P<0.0001) and it would appear that culture may miss more than third of dermatophytosis cases. Although qPCR is clearly the method of choice for diagnosis of equine dermatophytosis, the main limitation of the assay is its inability to differentiate live from dead dermatophytes following treatment, although a further addition to the assay is being developed that will deal with this issue.

Crusting/scaling skin disease with systemic involvement:

Natural resolution typically takes one to three months, although therapy is always indicated to limit ongoing environmental contamination. Isolation of clinical cases and “in contacts” is advisable, but often becomes a compromise between the ideal and the practical. Specific advice on the length of isolation periods is impossible to offer with any degree of certainty due to local infective spore contamination and the recovered animal then acting as a fomite to infect others. Isolation for two to four weeks following appropriate treatment is often advised, but may be insufficient in some cases. Fungicidal washes are likely to be more rapidly effective than systemic treatments. One to two weeks isolation beyond signs of clinical improvement (hairs regrowing on alopecic areas) appears to be reasonably pragmatic advice following treatment, although it remains possible further spread could occur beyond this time.

Topical treatments for dermatophytosis include enilconazole or chlorhexidine and miconazole, applied twice weekly for two weeks. It is important to wash a wide area or preferably the whole horse as, in human cases, it has been shown viable dermatophytes can be isolated from normal skin up to 6cm from the margins of the lesions. Exposure to natural sunlight (for example, turnout) may aid resolution, but adds to widespread distribution of infective spores.

Common pruritic skin diseases that may be associated with scaling and crusting:

Topical treatment of the tack, equipment and possibly the stable is advisable as spores will remain viable for years under natural conditions and serve to reinfect other horses. Sterilisation of tack can be achieved with ethylene oxide ampoules (offer service to client if gas-sterilisation equipment is available in the practice) or a wash with enilconazole. In an attempt to break the cycle of infection, stables should be washed in bleach, formalin, glutaraldehyde or a multi-purpose disinfectant. It should be suggested hands are washed in an antiseptic solution after handling infected horses.

This is an important differential diagnosis of dermatophytosis as both conditions are common, may coexist, are often visually similar and usually seen in areas subject to rubbing by tack. Haemolytic, coagulase-positive Staphylococcus species (primarily Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus intermedius) are the most common isolates.

S aureus isolates should be checked for cefoxitin resistance (implying meticillin-resistant strains). Experimental reproduction of the disease has been achieved by rubbing the skin and applying staphylococcal cultures.

Small papules initially develop and quickly lead to larger patches of crusts and matted hair, perhaps with local oedema (Figure 9). In the early stages the condition is, at least, sensitive, and, more often, significantly painful – a significant clinical difference from dermatophytosis, which is rarely worse than a little sensitive or mildly painful. Squeezing fresh lesions may result in pain and possibly the exudation of pus. Lesions may progress to erosions and a wet, oozing pyoderma or dry, circular, scaling, alopecic patches. Hair plucks and swabs from underneath freshly lifted crusts may be taken for culture and microscopy to aid differentiation.

Oral antibiotics are generally of limited use unless the infection is very deep (furunculosis).

Topical antibacterial creams and washes (ethyl lactate, benzoyl peroxide) are effective treatments, along with avoidance of further rubbing. Pretreatment with tar and sulphur shampoos may help loosen crusts. Dual fungicides and bactericides, such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine, may be useful in equivocal cases where there is uncertainty about a primary bacterial or fungal aetiology. The offending tack items should be thoroughly disinfected.

However, the clinician should always be mindful of a wider list of differential diagnoses when diagnostic aids fail to support bacterial or fungal causes, or when failure to respond to antimicrobial treatments is seen. Pemphigus foliaceus is an uncommon, but not rare, immune-mediated condition presenting as widespread crusting and scaling, and should be considered when more common causes seem unlikely.