13 Oct 2021

Madeleine Campbell BVetMed(Hons), MA(Oxon), MA(Keele), PGCert(VetEd), PhD, DipECAR, DipECAWBM(AWSEL), FHEA, FRCVS, reviews the indications for assessing female horses, including techniques commonly, and less commonly, used.

Image: Rokfeler / Adobe Stock

The winter period – when no time pressure exists to get mares bred as soon as possible – offers an excellent opportunity to assess mares that ended the past breeding season not pregnant and those about to embark on a breeding career for the first time.

This article reviews the indications for such a “breeding soundness examination” (BSE), and the techniques that are commonly and less commonly used.

Indications for undertaking a BSE include:

Mares are seasonal breeders, with the majority of them entering a period of cyclical quiescence (anoestrus) during the short days of the winter months. During this period, the mare typically has minimal (if any) ovarian follicular activity, no corpus luteum, and consequently, a tubular reproductive tract, which is under the dominance of neither oestrogen nor progesterone.

This means the uterus and cervix are of intermediate tone, creating an opportunity for prolonged intrauterine treatment without the need to battle against the closing of the cervix, which occurs regularly when a mare enters periods of dioestrus during the breeding season. For this reason, many BSEs of mares that have ended the previous breeding season not pregnant (“barren mares”) are undertaken during winter anoestrus.

The disadvantage of undertaking a BSE during winter anoestrus is obviously that it is impossible to determine whether the mare cycles regularly during the summer (irregularities of cyclicity during the physiological breeding season can be indicative of reproductive problems – for example, persistent endometritis or a granulosa cell tumour). The timing of the BSE will, therefore, depend on the reason it is being undertaken for.

Taking a careful history provides important information about a mare’s fertility. For example, if she was bred last season, but failed to get pregnant:

If the mare is being considered for use as an embryo recipient, what is known about her own breeding and foaling history? Previous laboratory test results – for example, those proving that the mare was tested free of venereal disease according to the Horserace Betting Levy Board Codes of Practice, any uterine biopsy results and any hormonal analyses – should be requested.

A history relating to the mare’s general health should also be taken, focusing particularly on any concurrent illness that might make it difficult for her to conceive (for example, pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction) or to carry a foal successfully to term (for example, deficits of the ventral midline musculature, respiratory disease, a predisposition to laminitis).

The clinical examination should commence with a general assessment of the mare’s condition and health, again paying particular attention to anything that might have a negative impact on the mare’s ability to conceive, to carry a foal to term and safely deliver it, or on the mare’s own welfare.

Poor condition can result in abnormal perineal conformation, which predisposes to intrauterine infections. Being overweight may also have an adverse effect on fertility. The impact of lameness issues on a mare’s fertility varies with the severity of the lameness – any issue that results in chronic pain, or in the mare not being able to move around and get up and down easily, may have a negative impact.

From a welfare point of view, one should consider the likely effect of carrying a large, mid-to-late term fetus on the mare’s lameness and associated pain. Chronic respiratory problems may reduce fetal oxygenation. If the mare is on long-term medication for any chronic condition, one should always consider the possible impact on embryonic/fetal health, and on uterine contractions at the time of foaling.

To undertake a clinical reproductive examination, and the additional techniques described later, the mare must be adequately restrained (in stocks), and sedated if necessary to reduce the risk of injury to the mare and to personnel.

The reproductive examination should start with an assessment of the external perineal conformation – is the vulva vertically aligned and straight, or is it sloping? Is the area around the anus sunken? Is there a “shelf” between the anus and the vulva? Such conformations predispose to aspiration of faecal material through the vulva into the vagina, and therefore (via the cervix) to uterine infection and inflammation.

A speculum and manual examination of the vagina and cervix is undertaken. The order these are conducted in is largely a matter of personal preference. This author prefers to undertake the manual examination first.

Having scrupulously cleaned/disinfected the mare’s perineum and vulva, one can introduce a gloved and lubricated hand through the vulva into the vagina. One should assess the integrity of the vestibular sphincter, whether any palpable abnormalities in the vagina exist, and whether the external os of the cervix has any palpable abnormalities (for example, adhesions or deficits).

Note it is crucially important in the mare never to breach the cervix until one is absolutely sure that the mare is not pregnant, since inserting anything into or through the cervix of a pregnant mare is likely to cause abortion. Caution should, therefore, be used at this stage of the examination, and if necessary the manual examination of the cervix should be deferred until – or returned to after – an ultrasound examination of the uterus has confirmed that the mare is not pregnant (see later).

On withdrawing the hand from the vulva, one should check the glove for the presence of fluid (for example, urine, indicative of urovagina) or blood (for example, indicative of a previously unperforated hymen or ruptured varicose vessels in the vagina).

A speculum examination of the vagina and cervix is undertaken using either a sterilised duck-billed speculum, or a disposable one, and a light source. The vaginal cavity should be assessed for fluid accumulations (urine or purulent discharge), varicose vessels and inflammatory changes to the mucosa. If a discharge is detected, one should try to ascertain its origin – for example, is discharge visibly coming through the cervix (and hence originating in the cervix or the uterus) or is it indicative of a vaginitis?

The position of the cervix and its state of relaxation help to determine the stage of the mare’s reproductive cycle (in anoestrus, the cervix will be pale and of intermediate tone; in oestrus the cervix is pink and relaxed, and the external os sinks towards the floor; and in dioestrus and pregnancy the cervix is pale, tight shut and horizontally orientated).

Using a rectal glove and lubrication, the rectum should then be manually evacuated and per rectum palpation of the reproductive tract undertaken to assess (i) whether the mare has normal reproductive anatomy and (ii) which stage of the reproductive cycle the mare is in.

Examining veterinarians should determine that the mare has one cervix, one uterine body, two uterine horns and two ovaries, and that the ovaries are of the expected size and consistency for the time of year, and in relation to each other (for example, one would expect both ovaries to be small in December, but not in June; one large and one very small ovary may be indicative of an ovarian tumour on the large ovary; or abnormal reproductive anatomy may be indicative of a chromosomal abnormality).

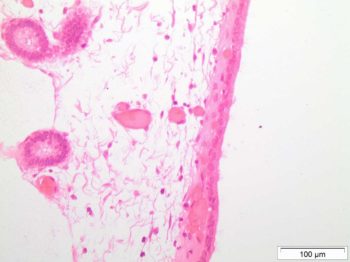

Once palpation is completed, one can progress to transrectal ultrasound examination of the reproductive tract (Ginther and Pierson, 1983). This is most commonly undertaken using a 5MHz or 7.5MHz linear array transducer. The veterinarian should assess the echotexture and diameter of the uterine body and horns, looking particularly for evidence of endometrial cysts (Stanton et al, 2004; Figure 1) and of intrauterine fluid accumulations.

The position and size of any cysts should be recorded, as should the depth, location and echogenicity of any fluid. As examples, cysts that are small and discrete are likely to have less impact on a mare’s ability to remain pregnant than a large group of cysts situated where the embryo nidates at the base of the uterine horn, which may inhibit movement of the early embryo throughout the uterus, and subsequently disrupt placental transfer.

Purulent fluid within the uterus generally has a fairly hyperechoic appearance; fluid that is the result of “urine pooling” in the vagina and subsequent aspiration through the cervix into the uterus is commonly found extending from the cervix into the uterine body.

Ultrasound of the ovaries should be undertaken to confirm the findings of palpation, that is, the size of the ovary, and the presence of ovarian follicles (size and number should be recorded), of any corporea lutea and of any structures with abnormal ultrasound appearance. Taken together, the palpation and ultrasound imaging of the reproductive tract should enable one to determine the stage of the mare’s reproductive cycle, the presence of normal anatomical structures and the presence/absence of any abnormal findings. Hormonal tests (see later) may be used to confirm these results.

The range of diagnostic tests that can be used to supplement the aforementioned clinical examinations includes (with the most commonly used first):

All mares being examined should have clitoral and endometrial swabs taken to prove freedom from venereal disease. The testing requirements and techniques for obtaining these swabs are outside the scope of this article, and are available at http://codes.hblb.org.uk

Endometrial swabs are also taken to ascertain whether an inflammatory process is going on and to identify non-venereal pathogens (for example, faecal bacteria, yeasts or fungi) within the uterus. Swabs may be obtained using either a guarded or a non-guarded technique (Riddle et al, 2007). This author finds that a guarded technique is less likely to give false positives due to contamination from the vagina.

Because of the possibility of contamination, swabs should be processed for cytology as well as for bacteriology, and positive culture results should be interpreted alongside the cytology results – in the vast majority of cases where a culture result is clinically significant, it will be accompanied by the presence of acute or chronic inflammatory cells in the uterus. Analysis of an endometrial biopsy (see later) also assists in this interpretation. Cytobrushes are also available for collecting endometrial cytology samples.

A technique for using a small volume lavage instead of a swab to obtain uterine samples for culture and cytology has been described (LeBlanc, 2010). This may be more sensitive than swabbing in terms of producing fewer false negative culture results, and is particularly useful in mares for which culture results from swabbing are repeatedly negative despite ultrasonographically visible fluid being present in the uterus, or in association with a persistent, unexplained failure to conceive.

Endometrial biopsy is indicated particularly in cases of previous known or suspected embryonic/fetal loss; for older maiden mares; for mares on which reconstructive reproductive surgery is about to be performed (because there is no point in undertaking the surgery if the endometrium is not capable of sustaining a pregnancy); and for mares being considered for use as embryo recipients.

The purpose of the endometrial biopsy is to ascertain the degree of inflammation and degeneration in the endometrium, and to give a prognosis for the mare’s ability to carry a foal successfully to term (Love, 2011). An endometrial biopsy may be taken at any stage of the oestrous cycle, providing that one has ascertained for certain that the mare is not pregnant.

If a biopsy is taken during dioestrus, prostaglandin F2α should be administered after the procedure to lyse the corpus luteum and bring the mare back into oestrus, so that the cervix will open and any contamination introduced by the biopsy procedure can be voided. Care should be taken in biopsying mares with pyometra, as the uterus may be friable and prone to rupture.

The biopsy is taken using endometrial biopsy forceps. The rectum is evacuated. The perineum and vulva are scrupulously cleaned/disinfected, and the biopsy forceps introduced through the vulva using a sterile, gloved and lubricated hand. The other hand holds the distal end of the biopsy instrument (outside the mare).

With the jaws of the biopsy instrument securely closed, the instrument is introduced through the cervix. The arm is then withdrawn from the vagina, relubricated and introduced into the rectum to palpate the biopsy instrument.

Once the biopsy instrument has been located, it is gently manoeuvred into position to take a sample from the base of one uterine horn. Using the hand that is outside the mare, the biopsy instrument is rotated into a horizontal orientation and the jaws opened (Figure 2).

The hand inside the rectum is used to gently press down, to introduce a fold of endometrium between the jaws of the biopsy instrument (it is important to be cognisant of the risk of rectal tear, and to use the minimum downward pressure necessary). The jaws of the biopsy instrument are shut. The arm is withdrawn from the rectum. A short, sharp “tug” is given on the biopsy instrument to acquire the sample, and the instrument is withdrawn via the vagina and vulva.

Using a sterile needle, the endometrial biopsy is moved from the jaws of the biopsy instrument into a container containing preservative media (typically Bouin’s fluid or formalin), provided by the laboratory to which the biopsy will be sent. One biopsy taken from the base of one uterine horn is usually representative – a second taken from the other horn may provide additional useful information. If ultrasound examination has revealed discrete areas of abnormality within the uterus, one should aim to biopsy those.

Endometrial biopsy is generally surprisingly well tolerated by mares – nonetheless, judicious use of sedation should be made, to minimise stress, and because of the risk of rectal tear associated with the technique. Occasionally, minimal bleeding from the vulva is noticed after endometrial biopsy. This is usually self-limiting. It is important to distinguish clearly between bleeding coming from the vulva (and hence the uterus) and blood coming from the rectum, to rule out a rectal tear – if in doubt, a rectal examination should be performed to make this distinction.

Hysteroscopy (uterine endoscopy; Figure 3) is used to visualise the uterine lumen and mucosa when a suspected abnormality has been detected by the preceding stages of the breeding soundness examination, or to pick up abnormalities that other techniques may not detect – for example, luminal adhesions, foreign bodies (such as marbles or lost swab tips) and uterine tumours (Brinsko, 2014). It can also be used to obtain a biopsy from a specific abnormal area of the endometrium.

Hysteroscopy can be performed at any stage of the oestrous cycle. As for techniques described earlier, it is crucial to determine that the mare is not pregnant before performing hysteroscopy, and the mare must be adequately restrained.

A 12mm to 14mm diameter flexible endoscope of at least 1m length is introduced through the cervix using sterile technique. The vagina and cervix are visualised (note, the mucosa typically becomes hyperaemic in the course of examination, as air is introduced through the endoscope to dilate the vagina).

The endoscope is passed through the cervix and the uterus inflated with air to facilitate visualisation of the uterine body, both uterine horns (the endoscope is “driven” up one and then the other) and the utero-tubal junctions. The uterus is deflated prior to withdrawal of the endoscope.

Because of the risk of introducing infection due to contamination (particularly associated with air insufflation) during hysteroscopy, many practitioners flush the uterus with sterile saline on completion of the procedure. If hysteroscopy is undertaken during dioestrus, prostaglandin F2α should be administered after the procedure, for the reasons described earlier in relation to endometrial biopsy.

Genetic testing/karyotyping (Lear and Villagomez, 2011) may be indicated where the preceding parts of breeding soundness examination has revealed abnormal reproductive anatomy (for example, an enlarged clitoris, which may be associated with sex reversal, or two small, inactive ovaries in the height of the physiological breeding season, which may be associated with chromosomal abnormalities; Lear and McGee, 2012). Such tests are carried out by specialised laboratories, and typically assess leukocyte DNA.

Other hormonal analyses, which may be relevant to support the findings of the earlier parts of a BSE, include assays for inhibin in cases of suspected granulosa cell tumour and measurement of equine chorionic gonadotropin in cases of suspected retained endometrial cups.

Occlusions of the oviductal lumen may be a cause of subfertility in mares with a history of repeatedly failing to conceive despite having been bred to a fertile stallion, undergoing normal ovulations and having no evidence of disease of the uterus or cervix.

Although oviductal patency tests have been described (Arnold and Love, 2013; Inoue, 2013), in practice diagnosis is usually made based on pregnancy diagnosis following breeding after endoscopic prostaglandin E2 gel treatment of the oviducts (Robinson et al, 2000).

This specialised surgery is usually performed in a referral centre, and may be indicated where the more routine tests of the breeding soundness examination have failed to identify a reason for subfertility.

On completion of a breeding soundness examination, the veterinarian should collate all of the results, and provide a written report detailing those results and the diagnosis of subfertility.

Recommendations should be made for (1) immediate treatment and (2) treatment during the next breeding season, if the BSE has been undertaken over the winter. The former might include, for example, correction of anatomical deficits of the reproductive tract, or antimicrobial intrauterine treatments. The latter should pay particular attention to treatments that will be needed in the period immediately before and after breeding, and any specific monitoring that is recommended during pregnancy.

A thoroughly performed BSE, particularly when undertaken during the non-breeding season, facilitates accurate diagnosis, and the formulation of an unrushed and specific treatment plan.

The cost to owners is offset either by increased chances of the mare conceiving and staying pregnant when she is next bred, or – if an untreatable cause of subfertility is diagnosed – by enabling the owner to make an economic decision to stop trying to breed from the mare.