19 Nov 2024

Mélanie Perrier discusses the developments made for diagnostics in horses.

Image © Svetlana / Adobe Stock

While radiographs, ultrasound and nuclear scintigraphy remain an important part of the diagnostic panel for advanced diagnostic imaging of equine cases, the past 10 years has seen an increase in the availability of other modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT)1.

Recently, the availability of standing CT has increased the use of this specific modality. This article will provide an overview of the latest advances seen over the past year in the use of CT for specific conditions, but in particular conditions of the neck and backs, where most of the advancement has been made. We will also briefly discuss some of the newer findings relating to ultrasonography and positron emission tomography (PET).

While MRI and nuclear scintigraphy are still widely used, no major advances have been seen with these modalities over the past few years, except for a better correlation between lesion type and clinical significance; therefore, this will not be discussed for the purpose of this specific article.

As CT has become more available across practices and universities in the UK and elsewhere, so an increase has occurred in its use to diagnose a variety of conditions and also allow better understanding of its main indications and advantages.

While, initially, CT was mainly used to diagnose head pathology (dental or sinus), more recently it has been used to look at neck and distal limb pathology, while some more up-to-date studies are looking into its use to diagnose caudal back and pelvis pathology2.

Some postmortem studies have described anatomical variations and pathological changes seen in the caudal lumbar vertebrae in horses. A recent study has shown that CT can be used in adult live horses to diagnose pathology of the caudal back and pelvis, and some of the pathologies diagnosed included osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joints and coxo-femoral joints, pelvic fractures and spondylosis3.

While radiographs provide a good screening tool for neck pathology, the clinical relevance of some findings is often questionable, and some lesions may easily be missed. Ultrasonography also remains a good diagnostic tool to assess the cervical spine – especially in combination to other diagnostic modalities.

Finally, nuclear scintigraphy is generally an insensitive technique for evaluation of the cervical spine. While MRI may be the gold standard for imaging the neck in other species – in particular for evaluation of cervical nerve roots and early intervertebral disc degeneration – CT is more available for evaluation of the entire length of the cervical spine in equine patients4.

CT has been used widely in the past few years to evaluate the cervical spine in adult horses. While up to recently neck pathology diagnosis was limited to clinical examination, radiographs and ultrasound, the wider availability of CT widened the assessment capabilities of that region.

While standing CT up to recently only allowed visualisation of the first two cervical vertebrae, under general anaesthetic, and depending on the size of the horse, diagnosis up to and including the fifth cervical vertebrae is now possible. Moreover, with the increasing availability of standing CT, these areas will soon be able to be imaged standing, too4-6.

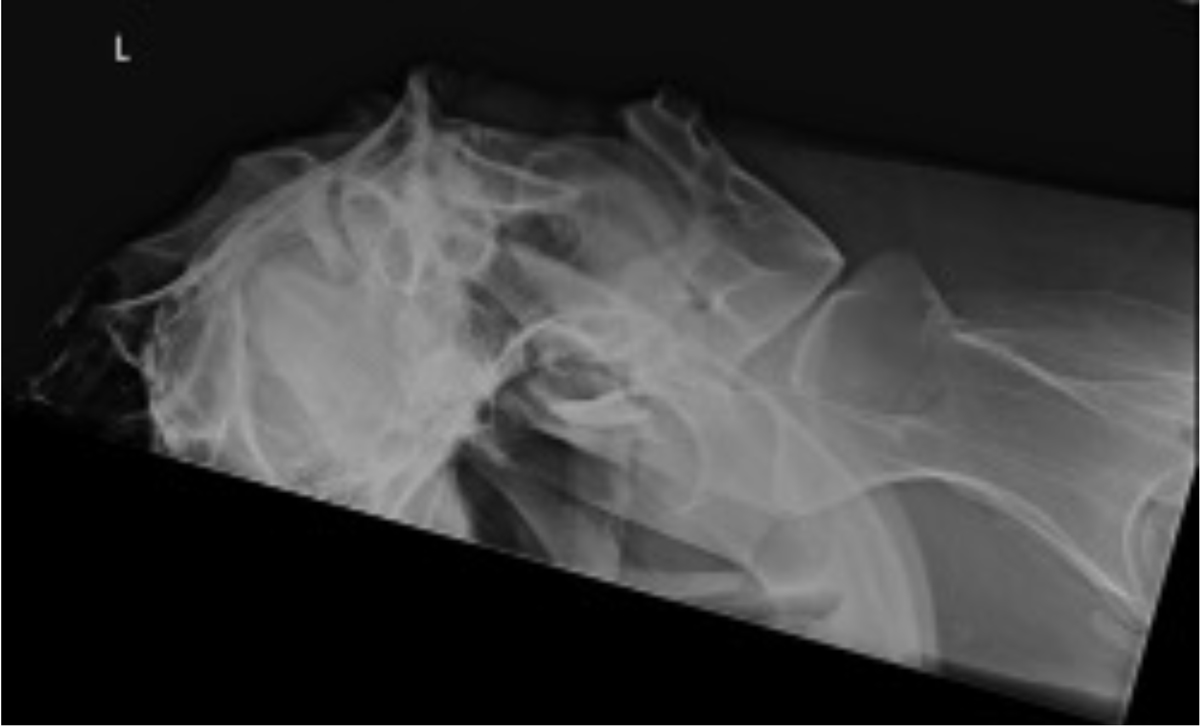

The increased availability of advanced diagnostic imaging has largely improved our ability to diagnose the cause of pain, or dysfunction associated with the cervical spine. Common pathology that can be involved include osteoarthritis and osteochondrosis of the articular process joints, fracture of the cervical vertebrae (Figure 1), nuchal ligament desmopathy, nuchal bursitis, cervical joint capsule fibrosis and synovitis, spinal nerve root impingement and radiculopathy secondary to osteoarthritis of the articular process joints7.

Figure 1a. Scintigraphic view of the left cranial cervical region of a mare presented for severe neck pain following a fall. Focal, moderate increased radiopharmaceutical uptake is visible in the ventral and cranial aspect of the atlas. Figure 1b. Oblique radiograph of the cranial cervical spine of the same horse. A radiolucent line is present at the left cranial aspect of the atlas with a slightly irregular margin. Figure 1c. A CT study of the neck was performed postmortem and confirmed a fracture to the ventral and dorsal cranial articulating surface of C1, in addition to the non-displaced, closed fracture of the caudal left articular process seen at C5.

Common findings on CT of the cervical spine include narrowing of the intervertebral foramen, degenerative changes, periarticular osteolysis, cyst-like lesion and fragmentation8.

In some horses, it has been shown that osteoarthropathy and enlargement of the articular process may result in cervical spinal nerve damage which may result in lameness. In these cases, CT myelography can be used to diagnose spinal nerve compression more accurately.

For horses in which a diagnosis of cervical spinal nerve compression has been made, a recent technique of endoscopic foraminotomy has been developed. This technique involves removal of impinging bone using a burr to widen the intervertebral foramen. This is usually performed under fluoroscopic guidance and also with the help of CT, both for diagnosis purposes and also postoperatively to assess the amount of bone removed9.

As mentioned, the use of CT for evaluation of distal limb pathology has also increased over the past few years10-11. It is now commonly indicated for evaluation of horses with pain associated with the proximal aspect of the third metacarpal/metatarsal region that does not improve with conservative management.

Publications have already demonstrated the usefulness of CT for evaluation of horses suspected of proximal suspensory desmitis, where high-field MRI is not readily available; this modality can reliably detect osseous proliferation, sclerosis, soft tissue enlargement and avulsion fractures12-14 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bone reconstruction CT images of the left, on left, and right forelimb showing small enthesophytes of the palmar aspect of the third metacarpal bone, at the origin of the suspensory ligament.

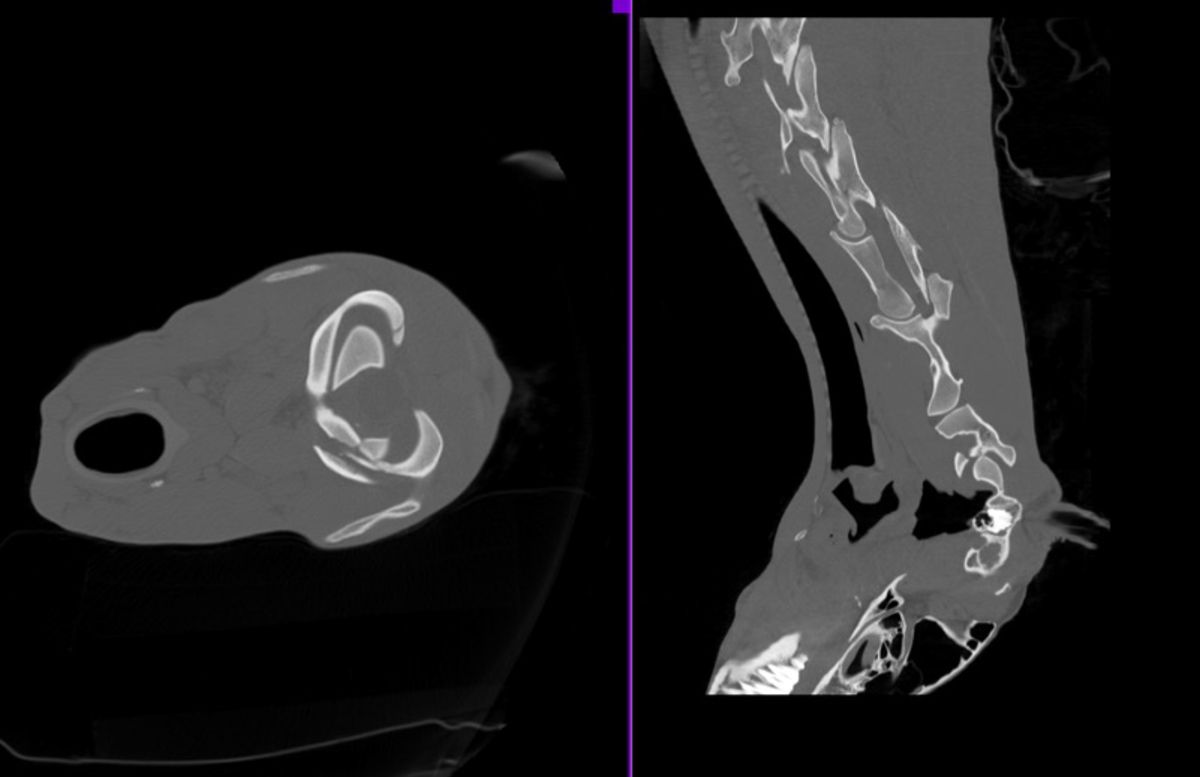

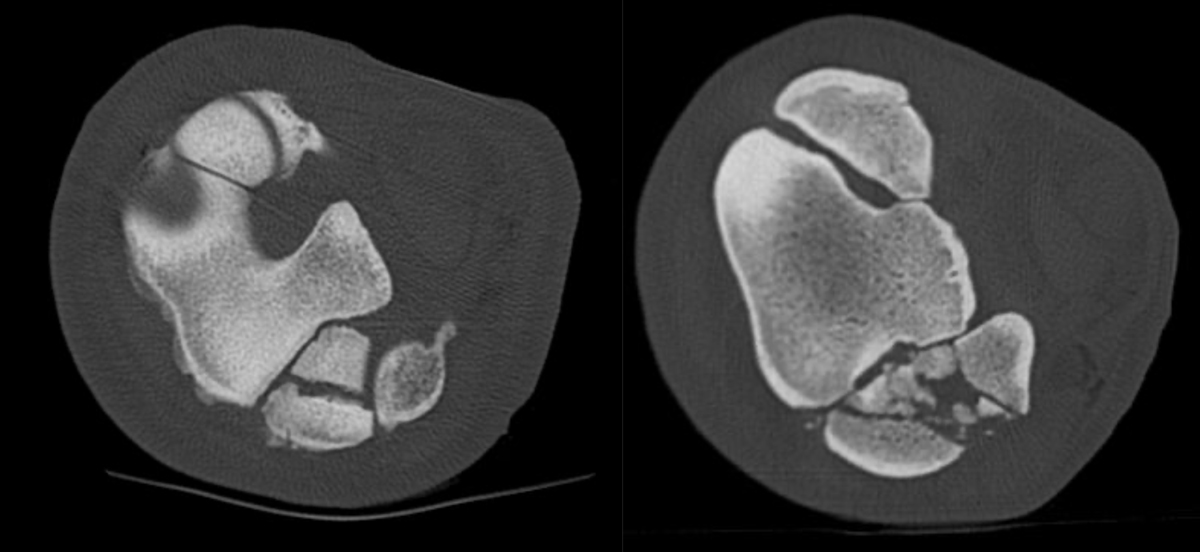

Other publications have evaluated the use of CT for characterisation of equine fractures15-16. One publication comparing radiography and CT evaluation of third carpal bone fractures found that CT identified comminution, displacement and length of the fracture more accurately than radiographs, which could in turn result in a better surgical repair15. Similarly, another publication looking at this type of fracture concluded in a more accurate diagnosis achieved with CT, potentially resulting in better surgical planning and outcome16 (Figure 3). In another study, more fractures of the distal limb were identified with CT than with radiography15.

Figure 3. CT images showing a severely comminuted acute articular fracture of the fourth carpal bone with moderate palmar and mild to moderate dorsal displacement of the fracture fragments. Multiple bone fragments are visible within the carpometacarpal and middle carpal joint.

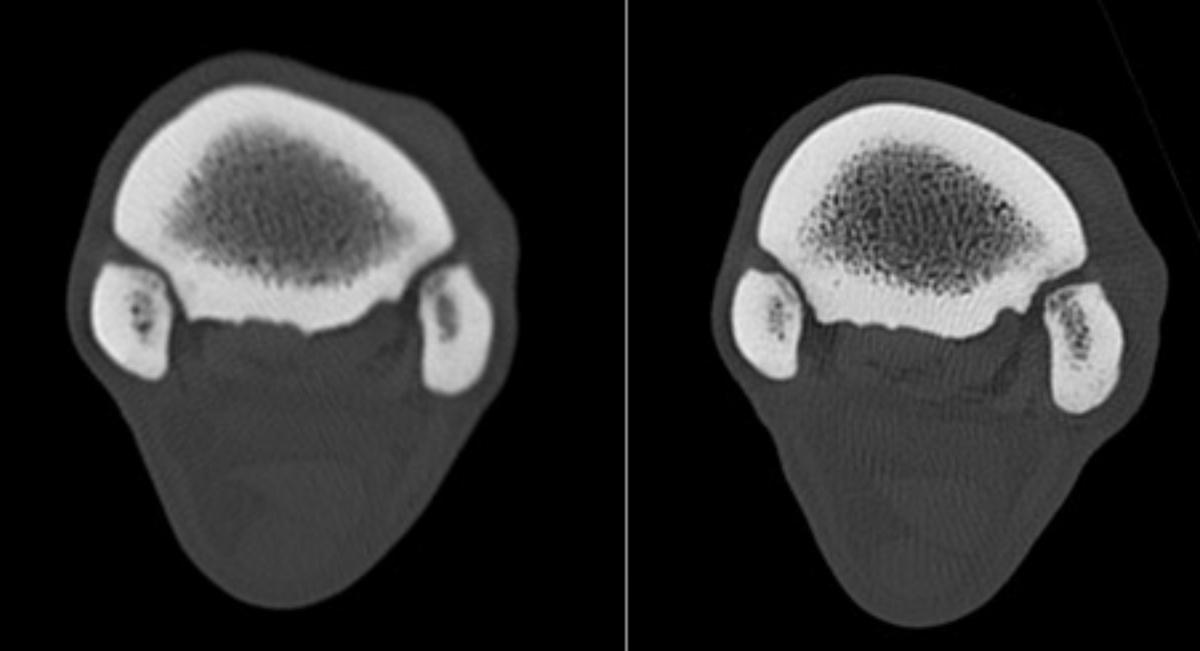

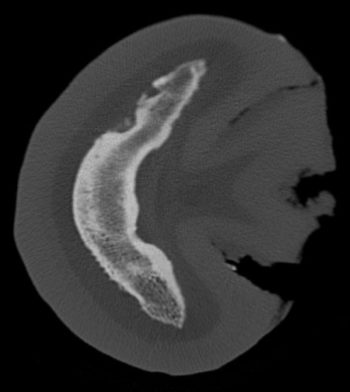

Finally, several publications have outlined the benefit of using CT in the diagnosis and treatment of keratomas in horses (Figure 4).

Effectively, CT allows for better and more accurate description of the size and location of the mass, allowing for better surgical planning and a lower complication rate by creating smaller hoof wall defect17.

While in most cases CT is used as a diagnostic tool, it is also commonly used in the planning and optimising of selected surgical procedures; for example, computed-assisted orthopaedic surgery has been reported for the repair of various equine fractures such as proximal phalanx, third metatarsal bone and ulnar fractures. This technique can also be used to remove articular fragments18.

Nowadays, many CT units can be coupled to surgical navigation software to improve surgical planning – in particular, studies have looked into the use of CT to elaborate 3D printed templates to facilitate surgical repair of certain equine fractures such as navicular bone fractures.

In short, the area of interest is imaged using conventional CT techniques and the images are imported to specific software for modelling of the anatomic structure. Following this, specific guides and inserts are 3D printed following three steps.

The first step is to determine the optimal screw positioning for the involved fracture. The second step is to design the specific guide to enable optimal drilling. The final step involves the creation and printing of the models.

The procedure results in a shorter surgical procedure, similar screw placement and lower fluoroscopic image acquisition during the procedure to achieve correct stabilisation of the fracture versus conventional fracture repair18-20.

Ultrasound remains one of the most widely used imaging modalities in equine practice. Colour or Doppler ultrasound has also helped differentiate more acute versus chronic injuries in tendinopathy in horses.

In an experimental study, blood flow was increased in surgically created lesions on the superficial digital flexor tendon for up to 23 weeks. While further studies are still needed, and taking into consideration that wide operator variability exists when using Doppler, it can be a useful method to determine the clinical relevance of a lesion and to subjectively determine the stage of healing of a lesion21.

Ultrasound is also helpful to guide medication and injection for various treatment purposes. One recent study has looked into the use of ultrasound for evaluation of the caudal lumbar region for both diagnostic, but also treatment purposes.

In cases of poor performances or horses with hindlimb weakness, transrectal ultrasound represent an integral part of the diagnostic process for examination of the sacro-iliac joint and intervertebral discs between the fourth lumbar and first sacral vertebrae. Some of the changes that can be found on ultrasound include irregular vertebral plates, variation in echogenicity of the intervertebral disc and displacement of the ventral longitudinal ligament, fissuration of the intervertebral disc, ventral hernia or dystrophic mineralisation.

All those changes may be associated with lower back pain and signs of poor performance in horses. While an integral part of the diagnostic arsenal, further studies are needed in this specific area, and the hope is that CT may help in better understanding some ultrasound findings. One study has already shown a high variability and anatomical variations of acquired pathology bony changes in the lumbosacral region, and a lack of correlations between ultrasound and CT findings in this region22-23.

Image © Roland Gruenewald / Adobe Stock

Ultrasound is also commonly used for injection of the cervical region, such as the atlanto-occipital space, the atlanto-axial space, the cervical articular process joints and the first cervical nerve and C2-C3 plexus and cervical nerve roots. Ultrasound guidance allows verification of correct needle placement in these cases and, therefore, helps improve the safety of the procedure24.

While ultrasound-guided injection of the cervical articular processes is now commonly performed to treat neck pain in horses, some recent studies have looked into the use of ultrasound-guided injection techniques for treatment of cervical root radiculopathy. As mentioned, the diagnosis of radiculopathy has been made possible with the wider availability of CT of the neck.

Horses usually present with hopping-type forelimb lameness and neck pain or stiffness. As mentioned, radiculopathy has been associated with compression of nerve roots secondary to osteoarthritis of the articular joint processes and narrowing of the intervertebral foramen.

One study investigated the feasibility of medication for the C3 to C8 cervical nerve roots under ultrasonographic guidance and found the technique had excellent accuracy, with further diffusion likely to improve success rate25.

Positron emission tomography, commonly called PET, is a cross-sectional nuclear medicine modality; similar to planar nuclear scintigraphy, it involves the injection of a radio marker, in this case a radioactive glucose, to obtain a dimension-dimension image.

While originally performed under general anaesthesia, PET scanning can now be performed in standing horses. By providing cross-sectional images, PET has the advantage of giving more specific localisation of lesions.

It also has the ability to detect changes that may occur prior to structural damage and, therefore, is often referred to as functional imaging. It is commonly performed in horses in combination with CT and MRI, which helps better interpret clinical usefulness of findings while providing additional information.

It is particularly useful to assess subchondral bone and enthesis, in particular in the foot, fetlock and tarsus region of the horse.

“[The] wider availability of certain modalities, together with the ability to perform certain diagnosis standing, has widened the diagnostic arsenal of the equine clinician…”

This modality can be viewed as enhanced bone scintigraphy: it is able to diagnose more abnormalities than conventional nuclear scintigraphy with the added advantage of being able to quantify the lesion; for example, in one study, increased uptake was identified in racehorses in the palmar metacarpal condyles and proximal sesamoid bones, where catastrophic breakdown may occur. Identification of these lesions early on would be crucial in preventing catastrophic injuries. It can also be used in combination with CT and/or MRI. This is particularly useful to diagnose pathology in the foot – such as active enthesopathy – particularly of the collateral ligament of the distal interphalangeal or the chondrosesamoidean ligament on the distal phalanx26-27.

As we have seen with MRI in the past, the wider availability of certain modalities, together with the ability to perform certain diagnosis standing, has widened the diagnostic arsenal of the equine clinician, allowing a more comprehensive diagnosis and treatment to be put in place.

CT has especially seen an increased usefulness over the past few years, and it is likely that the next few years will also see an increase in scientific evidence in that area. PET is another area of advanced diagnostic imaging that seems promising; however, its availability being still relatively limited, it is difficult to predict its usefulness over the next few years.

Finally, MRI still remains the diagnostic of choice for lesions in the foot, where radiographic evidence is scarce. Ultrasonography remains a widely available and affordable modality that should not be overlooked, whether for its diagnostic properties, either alone or in combination with other modalities, but also for its use in target treatment.