31 Jan 2025

Debbie Gray RVN, outlines the challenges veterinary nurses may face when trying to effect change in a practice, and shares some strategies to help achieve success.

Image: koumaru / Adobe Stock

Nothing is more frustrating as a veterinary nurse than being denied the ability to purchase a piece of equipment or kit that you know would not only have significant benefits to patient outcomes, but would also make the practice operate more effectively and allow you to be more efficient in your role.

Veterinary nurses are at the forefront of patient care and instrumental in achieving successful patient outcomes. So, why are we often denied such pieces of kit? A basic infusion pump can cost as little as £500 and a multiparameter monitor can start in the region of £1,000, and the benefits they bring far outweigh the investment.

Ever-increased access to new equipment and technology exists that saves time and avoids repetitive tasks. However, it isn’t just about convenience; it increases productivity and translates to money saved, and leads to improved patient care by allowing the nursing team to devote time to more complex patient care.

Perhaps we need to think about the way we “pitch” for these products and how we can best use our skills and knowledge to build a solid business case, and demonstrate the return on investment.

It is easy to sit back and think, “well that’s not my job” – it’s something the practice manager or clinical director should do. However, veterinary nurses are on the front line delivering the care to the patients and are instrumental in communicating the significant benefits that investment would bring.

Everyone, including managers and practice owners, is challenged with the complexities of daily tasks and running the business. Approaching the negotiation with a solution to a problem is often more beneficial than presenting just the problem.

From a personal perspective it also reflects your ability to take initiative and responsibility for improving practice, and demonstrates an understanding of the business element of veterinary practice. Furthermore, the experience you gain from doing such tasks will enable you to provide evidence when it comes to performance reviews for senior roles or progressing wider in the industry.

A good place to start negotiations is to have solid evidence to support and back your ideas. Well-structured research and documented evidence in a proposal is far harder to say no to than something verbally expressed as a suggestion or opinion. Auditing can be one option to help gain evidence to support your pitch.

The following are steps on conducting audits.

Begin with identifying the real problem or the gap in equipment requirement. For example, if you do not have a multiparameter or infusion pump, document the challenges it causes, the increased time that procedures take or the manual work that could be automated.

For example, an infusion pump would allow for accurate delivery rates and prevent accidental free flow of fluids, or a syringe driver would allow for precise and continuous dosing.

Get the team on board to help monitor specific situations over time and record the frequency of issues to evidence the impact of the problem.

Consider parameters that can easily be measured – that is, time, clinical parameters or patient outcomes and document the findings. Create a specific template that everyone uses to make collating the information easier.

Use the data to demonstrate how the equipment could help improve efficiency or patient care.

You may have recorded that it takes the nurse a total of 10 minutes to administer a specific dose of medication from start to finish; however, to set up the syringe driver would only take 2 minutes, which reflects a time-saving benefit of 80%, plus improves the accuracy in drug delivery.

Return on investment (ROI) is a financial performance measure that can also be included in the proposal. ROI compares the profit or loss from an investment, such as purchasing the equipment to its initial cost. You should also consider how often the equipment will be used, if all staff will be able to use it or if they will need to undertake additional training.

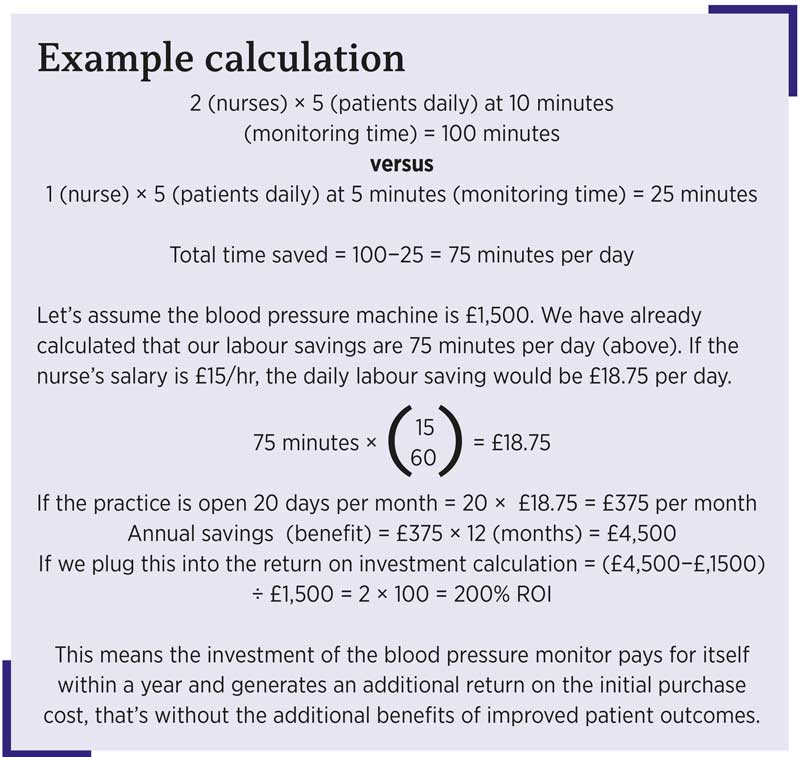

To calculate the ROI, you compare the financial gains or savings generated by the equipment against its initial cost:

ROI = (Total benefit (or saving) – cost of equipment) × 100

Cost of equipment

Let’s consider the example – you have identified that having an oscillometric blood pressure machine would be beneficial and would like the practice to purchase one. Currently, nurses are manually measuring blood pressure on a conscious cat. It may routinely take 2 nurses 10 minutes and may also cause a degree of stress to the cat. However, a modern, quiet, automated machine will require just one nurse, and readings can be obtained within five minutes, the cat will be less stressed and client satisfaction is likely to improve.

It could be argued that the aforementioned is speculation if you do not already have a machine to monitor the time saved. This is where you can make use of loan equipment and trial periods.

Some equipment suppliers will offer a free trial period, with no commitment to purchasing, for you to test the product. This is an effective way to get a good understanding of the equipment, make comparisons (if necessary), ensure it is fit for purpose and gather the evidence.

Calculating the cost per use of any equipment request can also be included in the proposal. This is a simple and effective way to reflect that purchasing equipment is not just a one-time cost, but a long-term investment. It demonstrates that you have considered the financial implications and it supports growth for the practice.

Using the same example, the cost of the blood pressure machine is £1,500. You use the machine 10 times each day and the practice is open 20 days a month (10 × 20 = 200 uses a month).

200 × 12 (months) = 2,400 uses annually. Divide the number of uses by the cost of the equipment:

2,400 ÷ 1,500 = £1.60 per use

This cost can also be factored into the cost of the procedure, which is an alternative way of recovering investment costs.

Once you have completed your first audit, don’t be afraid to think outside the box of the alternative ways in which the equipment can further benefit the practice. Maybe with the time saved you can offer a new service such as nurse-led senior pet clinics?

You can then incorporate further calculations to reflect the potential revenue generation from the clinics, which in turn helps justify the equipment expense.

Create a documented proposal and include all the key points. It should be concise and easy to read; think about breaking it into sections – for example, challenges faced (supported with data as evidence), the proposed solutions (purchase of equipment and staff CPD), cost analysis (ROI and cost per use) and the benefits (financial, patient outcomes and customer satisfaction).

Use visual aids such as graphs and bar charts to present data and make interpretation easy, and consider the language used, so rather than”‘we need this equipment”, think about using “by investing in the blood pressure monitor we could save £4,500 annually, which would give us time to run senior pet clinics and generate an additional x% more revenue on nurse clinics”.

Try to pre-empt questions that may be asked by including them in the proposal, and always be prepared for questions. Book a time to meet the person you will pitch to so that they give you, and the proposal, their full attention. Remember, if you do not get an immediate answer to ask when you can expect to hear a response and do not be afraid to follow up for an answer.

If you’re new to auditing, RCVS knowledge has a wealth of information on its website to support clinical audits in practice. A checklist can be used for planning and completing the audit. Donview Veterinary Centre (RCVS, 2024) provides a good example of a clinical audit and the purchase of new equipment.

It identified that patients were being returned to kennels with low body temperatures after procedures. The body temperatures of 31 patients were recorded, which provided data showing that 58% were hypothermic postoperatively.

The team discussed methods of improving patient care and a new standard operating procedure was implemented, and the practice invested in a fluid warmer, forced air warmer and thermo-blocker for the prep room table. The original data was then used as a benchmark to measure and reflect the improvement made.

CPD and training is available on these topics, but we are all guilty of doing the CPD that we really enjoy rather than doing CPD that develops different skills and knowledge. Progressing in your career and the direction you take is your choice; however, being able to demonstrate transferable skills is a huge asset that puts you in good stead to progress to a wide range of non-clinical roles within the profession.

In summary, there is no set way that you should approach negotiations. Your place of work, the culture and internal process are all different. Therefore, you need to determine the approach that works best for the investment required.

If proposals are rejected, be open to feedback and try to understand why that decision was taken. It might mean that you can negotiate on tweaking the proposal from purchasing two infusion pumps, to buying one now and the other in six months. Feedback is also essential for learning how to adapt future proposals.

To finish where we started, veterinary nurses are at the forefront of leading and can be highly influential. While our initial thoughts are often on improving patient welfare and outcomes, we must present proposals with a business mindset and demonstrate revenue profitability and opportunities for practice growth. If we all had our way, we would have access to all the new and fancy equipment, but veterinary practices must operate as a business to continue to offer services for veterinary care.

VN Times (2024), Volume 25, Issue 1, Pages 4-6