21 Nov 2017

Kit Sturgess looks at the decision-making process when prescribing nutraceuticals, reviews the available evidence and emphasises the importance of client comms.

IMAGE: Freeimages/Iquiz.

Nutraceuticals are derived from food sources purported to provide extra health benefits, in addition to the basic nutritional value found in foods.

Defined in the veterinary field as being “endogenous substances”, nutraceuticals are not regulated as pharmaceuticals. As a consequence, despite having therapeutic indications, they cannot claim to have specific treatment indications, resulting in these products claiming to “support, maintain or promote the health” of a patient in general or specific organ systems – for example, the bladder, liver or joints.

A dearth of evidence exists assessing the value of these compounds in the management of chronic disease. Where studies are available, most have not shown a clear benefit to the use of nutraceuticals.

In today’s environment of evidence-based medicine, this can make justification for their use difficult, but in many areas they are used in, proven therapies are lacking. Evidence shows, however, that in acute situations – for example s-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) to reduce toxicity associated with acute paracetamol overdose or lomustine side effects – nutraceuticals can be beneficial, indicating some, at least, have a clear therapeutic action.

It, therefore, becomes critical high-quality communication takes place with clients so they are aware of potential benefits and likely costs – namely, monthly spend and duration of treatment.

A general misconception exists that, as nutraceuticals are “natural” products, they must be safe. Therein lies a conundrum, as the only truly safe products are those with no biological action. The moment a product has a biological reaction, a risk of toxicity or side effects is apparent. The more active a compound is, the greater the tendency toxicity or side effects will be observed in some individuals.

Good-quality products should have a lower risk of contaminants.

It is important to realise the efficacy of a drug is dependent on the headline compound – for example, chondroitin –

but also the salt it is included as – for example, sulphate – as a different salt can significantly alter a product’s toxicity and adsorption. Different calcium salts have markedly different absorptive properties in the gastrointestinal tract, so any data supporting efficacy, potential toxicity or dose should relate to that specific salt and not the headline compound alone. This should mean the particular formulation being sold is bioavailable (that is, results in measurable plasma levels) and preferably be taken up by the target tissue (for instance, glucosamine).

Taking into account the aforementioned points, the clinician can then ask a series of questions to the manufacturer or in relationship to practice policy; the more “no” answers, the less likely the product in question is likely to be safe and efficacious.

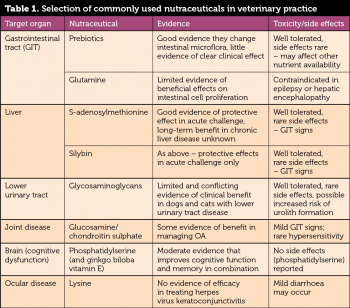

Table 1 lists some of the commonly used nutraceuticals, the target organ system, available evidence of efficacy and side effects/toxicity.

Nutraceuticals are most widely used as adjunctive therapy in chronic disease where the aim is management, rather than cure, or in early disease prior to more “traditional” pharmacological therapy.

Where nutraceuticals are used following a specific insult to an organ system where recovery is likely to be slow, they are rarely appropriate to be given in hospital, and risk the patient developing taste aversion associating with hospitalisation and feeling unwell.

This should mean nutraceuticals can be introduced once the patient is home and, in most cases, when its appetite is back to normal. When to start medication should be clearly communicated to the client – especially when it relies on another factor, such as return of appetite.

Duration of treatment or time of re-evaluation should be made clear to the client – preferably when the nutraceutical is first prescribed.

Discussion of ongoing costs should also occur. Long-term use of nutraceuticals can become a significant cost issue for clients, hence the clinician has to consider whether any benefit to the patient in short-term use can be seen (a few weeks), as well as how to make long-term use as cost effective as possible.

Long-term cost-effectiveness requires practices to approach prices the client can achieve online, along with emphasising the benefits of buying through the practice that should include:

Where nutraceuticals are being used for chronic non-resolving disease, it does not make therapeutic sense to use the product for a month and then stop unless some specific sign is being monitored, and treatments generally are being de-staged once those signs have resolved. Even under these circumstances, it could be argued the rationale for long-term use of the nutraceutical – for example, glycosaminoglycans in lower urinary disease – would be to reduce the frequency and severity of flare-ups.

For many patients, therefore, lifelong therapy is appropriate, balancing the costs, risks and benefits as far as the evidence allows.

For some nutraceuticals, there is at least expert opinion they are valuable as an early, or adjunctive, treatment in the management of a number of chronic diseases in cats and dogs. It is, therefore, critical the clinicians and practices are:

Such an approach should improve the client, clinician, practice and patient experience of nutraceuticals, as well as building a body of information that can be analysed via some of the big data studies to look at the potential long-term health and welfare benefits of these products.