11 Mar 2021

Brin McNeill BVMS, MRCVS, of Castle Veterinary Centre in Nottingham, offers some thoughts on EMS for students amid the pandemic with help from her daughter Cara, a third-year student at the University of Glasgow School of Veterinary Medicine.

Figure 1. Two-metre distancing is impossible for many tasks in veterinary practice, including induction of anaesthesia.

Coping with the COVID‑19 pandemic has, of necessity, changed the way veterinary surgeons work.

Among the many challenges facing the profession is the future of EMS, the real-life work experience that offers hands-on opportunities for students to develop the practical skills that enhance their university-based learning – and which many in the profession see as an essential part of the degree course. As one recent graduate commented, “EMS – that’s where the actual learning begins”.

However, the coronavirus outbreak and the subsequent restrictions necessary to keep staff safe has understandably meant many veterinary practices have cancelled EMS for the foreseeable future.

Under normal circumstances, veterinary students are required to complete a minimum of 38 weeks of EMS (12 weeks pre-clinical plus 26 weeks clinical) during their undergraduate training.

In response to the pandemic, the RCVS set up its COVID‑19 Taskforce, which decided that students scheduled to graduate in 2021 would not be prevented from qualifying – provided they had completed their 12 weeks of pre-clinical EMS and at least 50% of their clinical EMS.

The EMS requirements have now been reduced for students due to graduate over the next three years (Table 1) and the veterinary schools are delivering their degree courses via a “blended” approach, with lectures being delivered online while hands-on sessions are taught in small groups with social distancing in place.

Wherever possible, even practical classes such as postmortem demonstrations are being delivered remotely.

Final-year intramural rotations have been affected, and such restrictions in the teaching of practical skills will make access to EMS even more important for students.

Interested parties – such as the Association of Veterinary Students UK and Ireland, and SPVS – are in discussion with the Veterinary Schools Council to look for ways in which EMS can be offered by veterinary practices as we seek a realistic “new normal” for the profession while navigating a way out of the pandemic.

My experience as a practitioner – who, through circumstance, was perhaps one of very few to accommodate a student during the early COVID period, and who then felt confident to continue to offer EMS – has given me the opportunity to reflect on how the profession may provide placements in the months ahead.

My experience as a practitioner – who, through circumstance, was perhaps one of very few to accommodate a student during the early COVID period, and who then felt confident to continue to offer EMS – has given me the opportunity to reflect on how the profession may provide placements in the months ahead.

Cara, my vet student daughter, was completing her pre‑clinical studies at the University of Glasgow when she had to return home before Easter 2020 with the sudden imposition of the lockdown. This coincided with the need to find ways of managing our small, companion animal practice so it could continue to offer patient care while keeping staff safe as the pandemic took hold.

Fortunately, Cara had already completed her pre-clinical EMS, although she had been invited back to do a further lambing season at a local farm over the Easter period. This was – perhaps inevitably – cancelled, but it did mean she was unexpectedly available to work with us, and it offered an easy solution to the problem of making our rota workable with a team member who could easily fit into one of our “bubbles”.

The old adage “every cloud has a silver lining” seemed apt, as one student, disappointed to be forced home early, suddenly had the opportunity to gain some useful EMS.

As Cara had already arranged to do EMS with us later in the year, the placement had prior approval. The school’s EMS coordinator confirmed that, during the pandemic, they would be flexible with placements, but we were reminded that a student cannot do all their clinical EMS allocation at one practice. I was able to offer assurances that this would not be the case – apart from anything else, neither mother nor daughter were likely to survive the experience unscathed – but I did point out that, quite frankly, at this point any EMS was better than none.

Given that veterinary care is virtually impossible while maintaining two metres between staff (Figure 1), the onset of the pandemic required us – like all practices – to do a risk assessment and adopt methods to minimise the chances of virus transmission.

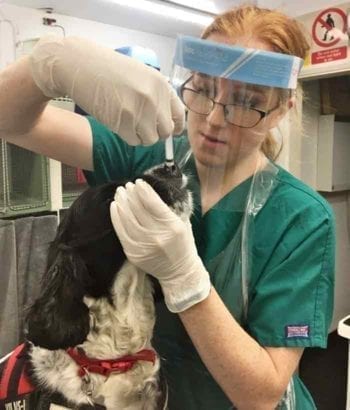

We insist on staff wearing PPE (gloves, mask plus visor and gown with a disposable apron; Figure 2), with everyone having their temperature taken on arrival for work each day.

As with most practices, we split into teams. Taking a student into a work “bubble” raised the risk level to some extent and required agreement from other team members; while it was easy to adopt Cara into the practice as she was already within our family bubble, careful thought is required if a practice is to take on an external student.

Some options that may help (Panel 1) include considering the use of rapid-result antigen testing, asking a student to self-quarantine for two weeks before EMS (and requesting he or she avoids large crowds and public transport before and during his or her time on placement), and identifying potential risk factors in his or her chosen accommodation during the placement. One solution for this final hazard may be to offer to feed and house the student during the EMS period.

Pre-COVID, it was standard practice to measure EMS in weeks. Currently, given that EMS attendance could be limited to joining a single staff bubble – and that case throughput in the average practice is probably slower than before due to car park vetting and similar protocols – it may no longer be appropriate to use such a simple measurement.

Our consultation time has been extended to allow for social distancing in the waiting room and disinfection between clients, so a student may see fewer cases than previously. Against that, some advantages exist – most practices have adopted “client remote” consultations, and with the owner absent from the consulting room more opportunities exist for a student to make a hands-on examination and to administer treatments (Figure 3). More candid and longer discussion of cases can also take place between vet and student.

For surgical procedures, although extra time is required to cope with the necessary PPE, things are pretty much unchanged. In-house lab tests, preparing repeat prescriptions and inpatient care – all integral to the EMS experience – run as normal.

Students are often very keen to get involved with the exciting parts of EMS (unusual cases, tricky surgery and exotic species) and are less enthralled with the more mundane tasks within practice.

“COVID EMS” may limit a student to shadowing a single vet, preventing him or her from moving from one unusual case to another and mixing with different practice staff.

But I take the view that students should experience all aspects of veterinary practice to ensure their expectations may match the realities of their first jobs – so Cara was expected do things such as regular cleaning duties and deal with difficult clients, as well as more “student-like” tasks such as taking blood samples, examining patients and scrubbing up for operations.

The pandemic meant she experienced some novel situations – she helped to develop and maintain biosecurity measures, and was tasked with addressing particular issues, including redesigning the dispensary to facilitate a one-way system to maintain social distancing. Importantly, she had first‑hand experience of problem-solving and adapting to new challenges.

We also expected her to do a fair share of reception work; this included answering the telephone, which involved triaging cases and advising clients about the many ways in which a visit to the vets has changed since pre-COVID days, and she was enlisted to take initial histories, put up and explain medication, and take payments.

We also expected her to do a fair share of reception work; this included answering the telephone, which involved triaging cases and advising clients about the many ways in which a visit to the vets has changed since pre-COVID days, and she was enlisted to take initial histories, put up and explain medication, and take payments.

Doing this in PPE and behind a perspex screen was perhaps initially challenging, but there can be no doubt these tasks allowed her to develop excellent people skills, which can only be good preparation for communicating with clients in the future.

So, while current policies may limit students’ access to clinical cases, they can open up opportunities for useful experience in other areas.

With all our consultations and treatments currently client remote and limited to one patient every 20 minutes, a constant pressure exists within the practice to keep to time.

We found that having a student who was an integral team member, rather than hovering in the background as an interested onlooker, became an essential part of enabling us to work efficiently.

By the end of her placement, Cara had completed the equivalent of 10 “weeks” of continuous EMS, and many vet students will no doubt feel a pang of envy when they read this. It is unusual for any student to undertake such a lengthy placement and would probably not have been countenanced pre-COVID.

No doubt exists that she has benefited from her fortunate and privileged position, but the experience has, we believe, provided a potentially useful template for EMS in the future. The prolonged assignment allowed her to become appreciated as a practice member and learn the value of teamwork, and because she has been able to learn our protocols and to take responsibilities, she has subsequently gained in confidence.

It has meant weaknesses in her practical skills have been analysed over numerous attempts, and we were able to offer her sustained advice and support to help her attain competency in many different areas.

In terms of surgical experience, as Cara’s skills improved and staff trust in her abilities increased, she progressed from simple suturing of wounds to neutering operations with appropriate supervision, without the return to the “start line” a student would normally face when he or she begins another EMS placement at a new practice. As a result, she had the opportunity to complete entire surgical cases from admission and sedation – through induction of anaesthesia and the procedure itself, to the discharge of the patient (Figure 4).

Following Cara’s successful integration of EMS during the spring lockdown, the practice has since had three more students on placement. We are currently restructuring our EMS plans for summer 2021 to accommodate longer rotations than previously (Panel 2), while bearing in mind that some sort of biosecurity to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 may still be necessary.

Following Cara’s successful integration of EMS during the spring lockdown, the practice has since had three more students on placement. We are currently restructuring our EMS plans for summer 2021 to accommodate longer rotations than previously (Panel 2), while bearing in mind that some sort of biosecurity to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 may still be necessary.

Taking a new person into a practice team at this time has its risks and while EMS is important, safeguarding human health must ultimately take precedence. Despite this, I believe the risks can be mitigated, although the number of placements a student can reasonably undertake in the time available may be reduced.

Longer periods in fewer practices might become the new normal – despite the potential disadvantages, such as a narrower range of experiences and the risk of a “poor” or unsuitable placement. However, our experience has shown this model may have significant advantages beyond the obvious one of enabling EMS to happen when otherwise it might not (Panel 3).

Providing the time to really address and iron out those little practical inadequacies that every student experiences – and, in particular, enabling the student to gain the trust of staff – will create more and more opportunities for students to obtain hands-on experience. This, in turn, will enable them to grow in confidence and hopefully make their transition into the workplace less traumatic than many seem to find it.

Practices considering how they can make EMS placements as safe as possible for staff and students during the coronavirus pandemic can find useful information from sources such as the SPVS website (www.spvs.org.uk).